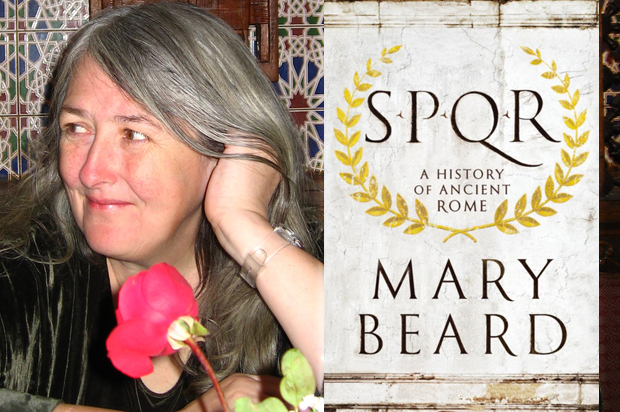

Cambridge University classics scholar, outspoken feminist, slayer of Internet trolls — Mary Beard is a genuine heroine in the United Kingdom. Her new book, “SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome” begins with a dusty village on the Tiber, debunks Romulus and Remus, looks closely at Cicero, moves through the period of growth and conquest, spends a chapter on the empire’s early heyday under Augustus, touches down on the weirdness of Nero and Caligula, and quits before things get really bad.

The book’s cryptic title – “the senate and people of Rome” – should not scare off readers interested in a smart, accessible, argumentative history written with great clarity.

“In some ways to explore the ancient Rome from the 21st century is rather like walking on a tightrope, a very careful balancing act,” she writes. “If you look down on one side, everything looks reassuringly familiar: there are conversations going on that we almost join, about the nature of freedom or problems of sex; there are buildings and monuments we understand, with all their troublesome adolescents; and there are jokes we ‘get.’ On the other side, it seems like completely alien territory.”

Salon spoke to Beard from her home in Cambridge, England. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

You seem especially interested in misconceptions about Rome – scholarly and otherwise. What have people who’ve studied Rome gotten wrong?

I think in some ways they’ve been too trusting of what they read. And I want to leave people with the fun of the Romans – Romulus and Remus, wicked emperors, I don’t want to take that fun away. We can have the fun, but we can still realize that all these stories we know about the Romans are constructed in much more complicated ways than that – and in some ways are much more interesting.

In some ways, you have to think hard about what the Romans are telling you. You have to think hard, for example, about what the story of Romulus and Remus is really about. Someone named Rolumus never existed. But the story is so important for understanding what Rome thought it was all about, that it’s worth looking very hard at.

So it is a bit of a balancing act I try to do. I don’t want to come along and say, “Oh, look, don’t believe any of this. This is all written by people who didn’t know…” I want to say, “Look, this is not necessarily literally true, and we can have fun with these stories. But there’s something really much more important: Why these stories are told is really interesting. I think the same thing about the wickednesses of the emperors, like what Tiberius got up to the in swimming pool… It’s important to understand why those were told. They were part of a propaganda machine. We have no idea of what Tiberius did in his swimming pool in Capri, and neither do the Romans who tell us about it. But we can also see we can learn a lot about Roman perceptions of power, about the wicknedness of autocracy that has gone wrong from those stories.

In some ways we’ve inherited them. We still have a terrible anxiety… Look at Berlusconi and swimming pools.

So we don’t have to believe [any of this] is literally true – but we can think hard about how we still think in Roman terms, how the Romans have given us our sense of what corruption is, what excess is… When we close our eyes and think about decadence, we have a Roman image in mind.

I wonder if this is true in Britain as well: In the States, a lot of us think of the Greeks as having come up with theater, democracy, philosophy, while the Romans were pragmatic, warlike, and – as you say – eventually decadent. Is there anything to these stereotypes?

That is the standard stereotype now… I’m actually quite keen on running water and lavatories and transport systems. So I think we shouldn’t knock those practical things.

But I also think that the heart of the Roman republic was an equally powerful and really important idea, which was liberty. Your founding fathers were well-read in Roman views in libertas – they were not all that interested in Greek ideals of democracy. At least, the Athenian idea of democracy – most city-states were not democratic and thought democracy was a very bad thing indeed.

What the Romans constructed was a version of civil liberties that we’ve inherited – what are the rights of the citizen against the power of the state? What about the right of the citizen to trial, to no arbitrary punishment – that’s an issue we face with terrorism every day now. As the Romans did: What’s the clash between the demands of homeland security and rights of the individual? We haven’t solved that, and they hadn’t solved that.

The other thing about the Romans: They’re trying to do popular politics on a massive scale. Fifth-century Athens – maximum 40,000 citizens. That’s the size of a college campus. The Romans are thinking about it with 700,000 citizens – that’s very different, and that’s our problem.

You have a lively chapter on Augustus. How similar was the real Octavian to the character in “I, Claudius”?

I still remember the “I, Claudius” television series, with the long Augustus death scene that went on for minutes and minutes.

The problem with Augustus: He’s a complete mystery. Here’s the guy who actually manages to establish a system of one-man rule that lasts for almost two centuries. Relatively uncontested. And yet we have the problem we have with some of our political leaders: He starts out life as a nasty, illegitimate thug who raises a private army and is effectively a warlord. He manages a transformation from warlord to elder statesman in a way that no other politician I know has ever done so speedily and so completely. It’s the big mystery of that period of Roman history. It’s a mystery the Romans themselves reflected on. They said that basically he was a chameleon.

Here’s a guy who took over the Roman state, defeated all his rivals, tearing out the eyes of his rivals with his bare hands… And then, fast-forward 10 years, and he’s the father of his country standing up for good old-fashioned Roman morality, and becoming the emperor that everyone else wanted to be!

Will the real Augustus please stand up?

A lot of scholars don’t enjoy being out in the larger world. Do you wish more academics would exist in the broader society the way you do?

Yes, I do wish they would – it’s a great privilege to work, and be paid, studying the Romans. It makes you study history, think about now, quite intensely. And to some extend, because the academy is still relatively protected, and people can speak without losing their jobs, there is an obligation to speak – not to rant, not to shout… The connection between the academy and the wider world should be stronger than it is.

I don’t mean at all that everyone [needs to be outspoken]. I hope there is still a role for people who spent their lives in the library looking at three lines of Aeschylus, or Homer, or whatever…. Not every academic has to be like me.

Do you still make an effort to chase down bullies on Twitter?

Yeah! They tend to keep off me now – so I have rather less opportunity to do this. I never had a plan or a strategy – I just did what came naturally. When people say awful things about you, I’d say, “That isn’t true. Please apologize, please take that down.” And it’s amazing how often they do.