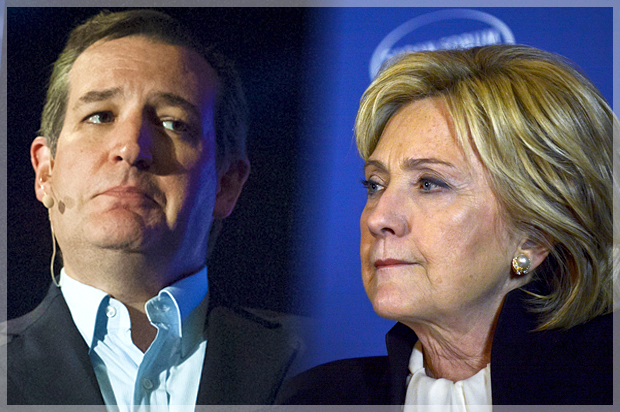

Senator Ted Cruz is, apparently, trying to be “likable.” The New York Times has a front-page story about the new push: “Known for Making Enemies, Cruz Tries, Stiffly, To Make Friends.” It’s a problem that the likely Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, has had for a long time. (“You’re likable enough, Hillary,” Barack Obama told her when the two were running for the presidency in 2008.)

But gender complicates things here. What do we expect from women in leadership positions? What makes a politician likable? How have things changed over the years? And what would it take for Ted Cruz to convince us he’s a fun guy to hang out with?

Salon spoke to David Greenberg, a professor of history and journalism at Rutgers University. Greenberg is also the author of “Nixon’s Shadow: The History of An Image” and “Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency,” due in January. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Ted Cruz is now chasing a quality that Hilary Clinton has long pursued, with varying success, for a long time. How far back have American voters expected their politicians to be likable? And how does gender change the terms of likability?

Likability has been an issue for politicians going back at least to the early 20th century — when we start getting the illusion of knowing their personalities, and we start seeing them in newsreels and seeing their pictures all over the place in tabloid newspapers, and hearing them on recordings and on the radio.

Television especially fosters this illusion of intimacy – we feel like we know them as people. When of course we don’t. It’s a question of authenticity, which is a slightly different facet of the same set of concerns.

I think, obviously, with gender we are still sorting out how we – and that goes for women as well as men – feel about women as political actors and political leaders.

Because female politicians, at the national level especially, are so recent in this country.

Yeah, exactly.

Even though we’ve progressed a lot as a nation in our understanding of women’s roles, there’s still a lot of baggage there. Women face a much steeper challenge in becoming liked because so much of the expectation on women to be liked relies on either cutesiness, flirtatiousness, sensitivity, a certain empathic quality – which are often seen as in conflict with traditional qualities associated with strong leadership. So the burden on women is to be able to exhibit both of those clusters of personality traits. Typically women are seen as falling into one category or the other. To be a strong woman who has credibility on, say, national security issues can require a certain toughness or gruffness – qualities we don’t always associate with likable women in everyday life. These are broad stereotypes, of course, and there are many women who pull it off. But that’s at the core of the dilemma.

To what extent is gender at the root of Hillary Clinton’s problems with this?

I think it’s one of the issues at the root, but I wouldn’t reduce it all to gender. I think she is inherently a guarded person. Unlike her husband, or unlike other women who are more personally ebullient, she is someone who is naturally calculating, strategic-minded, suspicious of the media – for good reason. Someone whose experiences in public life have reinforced those tendencies. She struggles with the expectation that our politicians be spontaneous and unfiltered and off the cuff, even though that’s only something we sometimes say we want.

So the likability issue comes up with her because she is not often enough given to spontaneity and warmth. Even though sometimes she shows that side of herself.

To what extent do other countries play the gender issue differently? Margaret Thatcher and Angela Merkel are hard to see as conventionally likable or traditionally feminine.

Certainly those women did not stress likability. They stressed strength, leadership, what we might with some degree of trepidation call a more masculine model of leadership.

What would it take to make Ted Cruz likable? His staff seems dedicated to making it work, but I’m not sure it’s possible.

Cruz’s problem – and it’s a problem for Chris Christie, and Giuliani a few years back – is they come to power, rise to prominence and popularity, precisely because of their mean streak. Because they’re seen as angry, they’re seen as not taking any b.s. from anyone… So again, in a different way, qualities of likability are at odds with the particular brand of leadership these men are purporting to offer.

Cruz just strikes me as someone who is just authentically a kind of ornery person.

And a know-it-all as well…

Yeah. His skill is he’s very practiced and fluent, whether in debates or other public experiences. He’s articulate and bright – he’s capable of a certain self-discipline. He can send some signals, talk about biography, talk about personal traits… That’s another aspect of this – the question of humanizing candidates… I found in my research, articles saying, “This year in the 1920 election, the candidate with the better narrative, or the better story, is going to win.”

Those do seem to sometimes work toward a more likable image. I’m thinking here of the Checkers speech. Nixon – who was one of the least likable politicians we’ve had in our history – really did pull it off. Cruz is, in his persona, somewhat Nixon-like.

But Nixon pulled it off at the time – he talked about his wife and his daughters and his dog. You watch that speech today and it seems very phony and mawkish, and many liberals felt that way at the time. But it was overwhelmingly a popular speech.

So it’s possible that with that Nixonian determination and practice, Cruz could talk about family, talk about personal experiences that tug at the heartstrings a little bit. And at least for a portion of the electorate that might not warm to his straight-up demeanor, he manages to reach them in ways he hasn’t so far.