After news broke last week that Erika Christakis, the Yale House Master whose terminally offensive email set off a wave of protests, decided to give up her teaching position, conservative columnists went wild. Christakis was characterized as a victim of the “free-speech surveillance state” she’d denounced back in 2012. Are you happy now? Christakis defenders goaded. I can only speak for myself, but no. Abandoning her teaching role while keeping her cushy and prestigious role as Associate House Master was the precise opposite of what I wanted from Christakis. The former was a narrowly tailored academic position. In the latter she is, and will continue to be, charged with defining the living experience of a broad swath of the student body. It is in this role that she failed, miserably.

But what was, perhaps, the most telling was not the absurd suggestion that her voluntary resignation signaled the collapse of academic freedom successfully wrought by the p.c. police. It was, instead, a failure to characterize Christakis as lacking “resilience,” a charge that was happily levied at the students who’d taken offense at her words. That some are more inclined to demand “resilience” of our minority students than our white administrators is damning. For only the feelings of minorities are obstacles to be overcome, and only the feelings of white people are worth protection. “Resilience,” as so-called defenders of free speech would define it, amounts to sitting down and shutting up.

In a society whose impulse is to shield white points of view from criticism while silencing minority ones, the ongoing protests demand a great deal of fortitude. It is a show of inner strength to declare one’s feelings relevant in the face of national scorn and mockery. Some such protests revolve around renaming institutions whose namesakes were venomous racists: the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs of Princeton and Calhoun College of Yale. It is unsurprising that they have drawn similar ire, as they attempt to correct similar indignities. What does it say to students that their schools continue to laud those who would have balked at their presence? How could it possibly serve as anything but a reminder that this institution was not built for them? That they are not welcome there?

The counterargument — the idea that renaming institutions somehow amounts to an erasure of history — is itself one of historical ignorance. These buildings are named after men who rose to positions of tremendous power and influence, men whom no comprehensive study of history could leave out, who are in no danger of being forgotten. But a comprehensive study of history would also note that they all had contemporaries who were horrified by and openly rejected their hateful views. Only the most perverse forms of moral relativism would brush off their gaping character flaws as a product of their times. Yet that is precisely what it means to equate history with the celebration of Great Men. It is to renounce a true grappling of history in all its complexity and nuance.

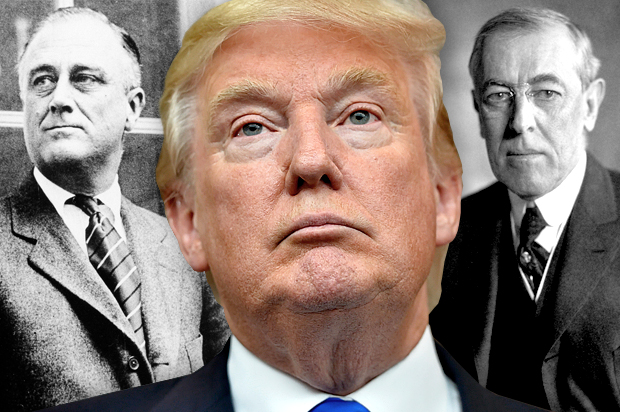

These matters are not unimportant or trivial, and they have parallels in the national political landscape. “Make America Great Again,” Trump shouts, harkening back to the good old days when our abused and disenfranchised were even more downtrodden. Progress is dangerous, his slogan warns his supporters. And to others, to those who’ve seen vast gains since those good old days, it is yet another reminder. Your feelings are not relevant. This country was not built for you. You are not welcome here.

When George Stephanopoulos of ABC News recently asked Trump whether he was troubled that his Islamophobic policy proposals were drawing Hitler comparisons, he was unfazed. “What I am doing is no different than what FDR did,” he said. “This is a president who is highly respected by all…he’s one of the most highly respected presidents…They named highways after him.” And he isn’t wrong.

These bigots are on the wrong side of history, the argument goes. But how can we claim that in good faith? It is not 1837. Or 1913. It is 2015. In the present day, students still receive their educations in institutions named after people who believed and said the most vile and reprehensible things about them, and who actively acted upon those beliefs and words. That our adulation of these men is ongoing indicates that a determination was made — that their status alone is enough to merit admiration, winning is everything, that the good they did outweighed the bad. Which is easy to say when both the good and the bad they did benefited your ancestors, and much harder to say when your ancestors bore the brunt of their mistreatment. To challenge our impulse for deification is to welcome America’s abused and disenfranchised into the national conscience.

The debates and decisions that we are having and making today are part of our history, too. A history that, thus far, has been one of absolution. And while these institutions ought to be renamed, to modify them physically, to strip Wilson’s and Calhoun’s names from the buildings that today bear them proudly, would serve to absolve ourselves. Leaving the physical buildings unaltered while renaming the institutions themselves would make them not monuments to our past, but shameful reminders of our own fallibility, testaments to the dangers of canonization.

Our history, of course, amounts to more than an accounting of our sins. America’s diversity challenges us to find pride in some underlying commonality. But in a nation with our past, self-aggrandizement is not an inclusive value. If America has a shared culture worthy of celebration it is not that of hero-worship, it is that of striving. In the individual sense, yes, but in the collective one as well. To be more reflective, more thoughtful, more moral today than we were the day before, more tomorrow than we are today. Not to make America great once more, but to make America better still.