My mother clutches the drumstick in her hand, growling like a dog. A spark of menace in her eye, she gnaws at the bone, maniacally shouting “The cartilage!” over and over. I sit staring at her across the Thanksgiving table, mortified.

My mother clutches the drumstick in her hand, growling like a dog. A spark of menace in her eye, she gnaws at the bone, maniacally shouting “The cartilage!” over and over. I sit staring at her across the Thanksgiving table, mortified.

This gruesome theatre has been part of the entertainment at family holiday dinners for each of my 24 years because we are all the descendants of cannibals.

In the early 1800s an immense sperm whale collided headlong with a ship that carried some of my mother’s ancestors, leaving them at the edges of the Earth without hope, and eventually they were forced to eat one another to survive.

“Your mother’s gone off the deep end,” my dad says, pretending to fight with her over a piece of turkey skin. Moments later, against a backdrop of holiday jazz and maybe even softly falling snow, my dad reaches a hand slowly over to my mother’s plate, feigning a look of fear. My mother, fully committed to the shtick, snaps at him, protecting the bare turkey bone as if she is a famished wolf. This bit always gets big laughs.’

More from Narratively: “How An International Man of Mystery Scammed My Grandma”

Growing up in New England, I cringed every time drumsticks were first pulled off a glistening bird, knowing that we were all about to engage in a rousing torrent of jokes about consuming human flesh. It’s the equivalent of announcing to friends and relatives we’ve welcomed into our home that we are a group of feral savages. There’s a sense in our family that the story is a point of pride, as well as a riveting party tidbit. I long avoided learning more about the tale of the ship and its survivors, refusing to read the literary classic it inspired — Herman Melville’s Moby Dick — hoping that our grim relation to it would, like so many other family tragedies, become lost in the skeins of history.

More from Narratively: “Can German Atonement Teach America to Finally Face Slavery?”

These days I’m an environmental reporter and writer. I think about whales and the business of slaughtering them almost daily, frequently investigating illegalwhaling activity and exploiting those who take part in it. I know all too well the way a whale thrashes in its dying moments, a fact that’s made it difficult to confront my family’s past as a whaling powerhouse. For years, I’ve felt that a person who can look at a whale and see only blubber and meat must be a sociopath, that whalers had been robbed of some sort of fundamental human compassion for animals bestowed to the rest of us at birth. But like it or not, my family history will never change, and the current Cronin crop certainly aren’t going to stop joking about it anytime soon. It’s time to face the 195-year-old tale — a leviathan itself.

* * *

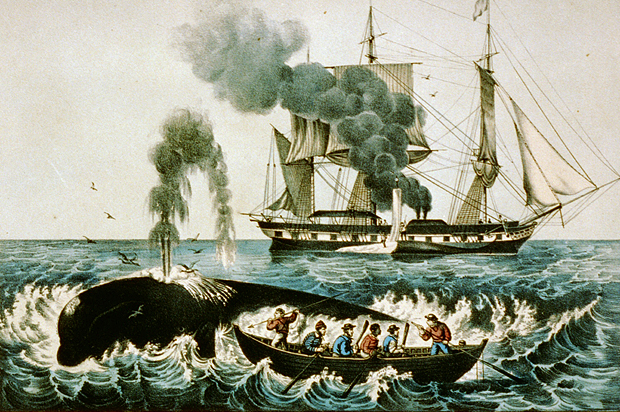

On the sunny morning of November 20, 1820, the deafening crunch of splintering wood rang out across the waves churning thousands of miles off the western coast of South America. A massive bull sperm whale slammed his body across the hull of the Essex, from whose deck men were trying to harpoon him and render his blubber into energy. Turning back toward the ship again, the whale began gathering momentum. Another thunderous crack. At an approximate speed of six knots the whale struck the hull, sending a quake shuttering through the boat’s oak beams, and stopping it dead in the water.

The Essex wasn’t much longer than the whale, an abnormally large monster that stretched 85 feet from head to fluke, the crew estimated. The whaling ship, already old for its time, now had a hole in its bow bigger than the whale’s enormous mouth, and was filling with seawater fast.

In the weeks prior, the Essex’s crew had ripped the blubber off of several whale carcasses and thrown them back to sea — the bones and gristle sinking down to rest on the sandy bottom, the skin decomposing in the darkness. This practice, one that still continues today, is a horrific scene to watch. Once the whale is harpooned, a fountain of blood begins to color the water, spreading out like ink. In the past, whales would drag a boat’s crew for hours after being harpooned, a tradition referred to as a “Nantucket sleigh ride.” When the animal was exhausted and on the brink of death, only then would it slow down enough to be shot or stabbed to death. Even with today’s explosive lances and automatic weapons, most whales have to be harpooned and then shot multiple times as they buck around in the waves by the motor of an enormous steel ship, hooked like a fish on a line.

But that’s not what played out that fateful day the Essex was attacked. After its shellacking, the ship, more than three times the weight of an average sperm whale, was breaking apart. The deck was sliding away from the hull; casks of oil were seeping from its seams. The valuable liquid spewed out onto the waves, a massive slick returning to the ocean where it was made.

The 29-year-old Essex captain, a stout and simple man named George Pollard Jr. — my distant relative — ordered the men to quickly load food and water onto three small, more maneuverable boats that were typically used in the harpooning stage of a whale hunt. A small herd of Galapagos tortoises and pigs swam from the ship out after the lifeboats and were loaded aboard too. They’d been picked up on tropical islands during the ship’s three-month journey from the Massachusetts whaling island of Nantucket.

The whalers and their animals now could only sit and watch the wretched dying throes of their ship as it sank. The twenty men cowering in three small whaleboats feared that they too would soon face the same fate. It wasn’t a preposterous thought. At latitude 0°40 south, longitude 119° west, they were just about as far away as one can possibly be from a large land mass anywhere on earth.

* * *

On February 6th of the next year, 90 days after the Essex sank, four of the survivors stood on a small whaling boat, the Dauphin, 1,500 miles from the coast of South America. They’d eaten the turtles, their flesh cooked in their own shells. They’d eaten the pigs and even the few flying fish that had smacked into their sails. When they were about a day away from starving to death, the remaining survivors agreed they would draw straws to see who would be sacrificed so the rest of the crew could live. A seventeen-year-old-boy named Owen Coffin, the cousin of Captain Pollard and another ancestor of mine, drew the unlucky lot. Having promised Coffin’s mother back ashore to protect him, Captain Pollard reportedly offered to sacrifice himself in the boy’s stead. Coffin refused. “No, I like my lot as well as any other,” he said, as the story goes, putting his head down on the boat’s sideboard in preparation.

In the middle of the boat, one of the survivors held a gun to the boy’s head and squeezed the trigger. They then cooked his flesh over a small fire and devoured it.

One more member of the Essex’s crew, also a teenager who, like young Coffin, was out on his inaugural trip to sea, would die from starvation before the little boat was rescued by the Dauphin less than a month after Coffin’s death. Pollard and a young mate, both nearly skeletons, were curled up in it, the floor a ghastly graveyard filled with the bones of their fallen comrades. They each held a bone to their mouths, sucking on the little marrow that remained inside.

In his vivid retelling of the Essex disaster, In The Heart of the Sea, maritime historian Nathaniel Philbrick writes that the two survivors “jealously clutched the splintered and gnawed-over bones with a desperate, almost feral intensity, refusing to give them up, like two starving dogs found trapped in a pit.”

* * *

“It was a resource,” my dad once said in response to my sentiments on whaling. He pointed out that, while I don’t eat meat, I sometimes eat fish — another resource that, like whales, must be hauled onto the decks of ships and, at least when coming from some fisheries, has disastrous effects on ecosystems. The story of the Essex features prominently in my family’s history, and it’s undeniable that we come from a long line of whalers. In fact, it’s impossible to tell the story of the Coffins and their relatives, including Captain Pollard, without also telling the story of whale hunting in America — a fact that has never been far from my mind.

It stands to reason that without the lucrative inputs of big business whaling, the Coffin family may not have become so, shall we say, fecund: It’s doubtful that the family would have gone on to produce thousands of descendants without the economic success they built on the carcasses of dead sperm whales. Therefore, it’s quite possible that without whaling I wouldn’t exist.

When I told my parents that I was looking into our family’s history for this story, they were excited — after, of course, the requisite cannibalism jokes. Though I’ve heard the story ad nauseam, it wasn’t until now that I actually traced my lineage back twelve generations to the prominent Englishman Tristram Coffin, who settled the 105-square-mile island of Nantucket in 1659.

At 24 miles from the coast of New England, the settlers of Nantucket had mastered the art of the sperm whale hunt by 1750, raking in the valuable spermaceti, a waxy substance found in the behemoth’s head cavity. Whalers harvested the stuff by the bucket, some 500 gallons per head. The wax was squeezed to create expensive oil — and to support the entire economy of the tiny island. Nantucket and its successful families quickly became the world’s best whalers.

When Captain Pollard took charge of the 238-ton ship, on loan from its two wealthy owners, he had no idea of the horrors he was dragging his 20-man crew into. Only eight would survive the wreck: two in one lifeboat, three in another, and three more who elected to await rescue on a remote island. All of the whalers in the lifeboats had eaten at least one of their comrades. But back on Nantucket, people were accustomed to seamen having to survive after wrecks, and didn’t fault survivors for resorting to cannibalism. Pollard and the other survivors were quietly welcomed back to Nantucket after the disaster, and most made lucrative careers for themselves in the seafaring business.They weren’t outcasts — but, in true Quaker fashion, no one spoke about the incident or even wrote about it in the paper. One of the most tragic events in Nantucket history was categorically swept under the rug.

The story of the Essex in particular — the real-life war between man and whale — and its crew have been told many, many times, from the firesides of Nantucket to the pages of Moby Dick, the classic by Herman Melville, who heard of the story of a “vengeful” whale attacking a ship during his own whaling journeys and even met Captain Pollard on Nantucket. Most recently, there’s the soon-to-be released “In the Heart of the Sea” film directed by Ron Howard based off Philbrick’s book. The film portrays Captain Pollard, Owen Coffin and the rest of the crew in their struggle to survive — a story that is bound to be retold in various forms for as long as humans and nature collide.

Nowadays, the climate on Nantucket, an island whose every establishment, gift shop and inn is adorned with the goofy, smiling countenance of a sperm whale, is similarly contradictory when it comes to whaling.

“The island has an interesting relationship to whaling,” Michael R. Harrison, the Chief Curator at the Nantucket Historical Association, told me. “If you ask any man on the street in Nantucket, he’ll say that the practice of whaling is ridiculous, and that he doesn’t support it.”

“Everybody embraces the fact that Nantucket was built on whaling,” he said, adding that, to the people of Nantucket, the gruesome realities of whaling don’t tarnish the island’s heritage. “It’s palpable; it’s part of its identity.”

I can’t help but feel kinship with these people, who are torn between familial respect for the success of their ancestors and disgust at the methods with which they achieved said success. I’ve spent my career lending a voice to animals that don’t have one, ignoring the nagging feeling that it was those animals’ deaths that allowed me to live. Can I really judge the sins of my forefathers, without acknowledging that those sins delivered me here?

* * *

The discussion about whether to slaughter whales for their meat and oil or to venerate them for their acumen has been ongoing for centuries. It’s no secret that the men aboard the Essex viewed the whale as an otherworldly beast living in an alien ocean, and even as their mortal enemy. In an account written by the first mate, a young man named Owen Chase, years after the wreck, he described the attack as one of “decided, calculating mischief.” Weeks later, in the middle of a grim night on one of the small lifeboats, Chase wrote of a pod of sperm whales that surfaced in the darkness — as if the starving and bedraggled crew hadn’t been through enough:

“…Our weak minds pictured out their appalling and hideous aspects… blowing and spouting at a terrible rate.”

But peoples’ opinions of whales aren’t always negative. This fall, I finally readMoby Dick, a book that I had been putting off, fearing the knowledge of my family’s own gruesome history would be too disturbing. The novel contains sentiments about whales similar to those of Chase, depicting them as ferocious monsters that must be tamed. But there are also indications that Melville and his compatriots understood that the whale was more than a chunk of blubber and meat. Melville writes of the whale’s tail:

“In no living thing are the lines of beauty more exquisitely defined than in the crescentic borders of these flukes… those motions derive their most appalling beauty.”

Whales, to Melville, are both magnificent, otherworldly creatures, and resources ripe for the pillaging. It’s these two ideas of the whale that I, hundreds of years later, am still grappling with. While whales — Captain Ahab’s notorious White Whale, in particular — are continuously referred to as “monsters,” there’s the sense that whales are natural resources, that their death serves the betterment of the populace, and that, in bloody sport, they are providing for future generations of people, like myself.

In his description of the killing of a whale, Melville acknowledges that it is difficult for whalemen to see such a large animal reduced to blubber and skeleton and then actually eat its meat:

It is not, perhaps, entirely because the whale is so excessively unctuous that landsmen seem to regard the eating of him with abhorrence; that appears to result, in some way, from the consideration before mentioned: i.e. that a man should eat a newly murdered thing of the sea, and eat it too by its own light. But no doubt the first man that ever murdered an ox was regarded as a murderer; perhaps he was hung; and if he had been put on his trial by oxen, he certainly would have been; and he certainly deserved it if any murderer does. Go to the meat-market of a Saturday night and see the crowds of live bipeds staring up at the long rows of dead quadrupeds. Does not that sight take a tooth out of the cannibal’s jaw? Cannibals? Who is not a cannibal?

Melville’s admits that in killing and eating something that’s not traditionally killed and eaten, we all cross the social taboos of our ancestors. In hindsight, whaling as an economic necessity is, I’ll admit, acceptable. But now, even after acknowledging my own family’s complicity in the slaughter of whales, my resolve is firm: without necessity, whaling is wrong, and it’s not hard, knowing what we know now, to deny that. In the twenty-first century, we don’t need to kill whales anymore, and so it’s unacceptable, in most of the world, to kill them. We don’tneed to eat other people to survive, and so it’s abhorrent to do so. In the same way, the shifting cultural acceptance of whaling is appropriate only to this moment, from the safe distance of 200 years of economic progress.

It’s hard to read this passage and not picture my mother, stifling laughter, chewing on the stripped leg of a turkey, as we sit around the table, its legs groaning under the weight of the food that we can buy because we were lucky enough to make it here, fed on the fat of whales and on the marrow of our relatives.

Every Thanksgiving, we repeat the routine: my mom pretends to jealously guard her turkey bone, while relatives laugh and new friends stare in horror until they realize it’s a joke. In a way, recalling a ghastly history so incomprehensible as ours is only possible in jest. We can’t imagine what it was really like on that boat, to throw a lance into a whale, nor can we imagine what it was like later, to chew something that was once your friend. But especially at this time of year, it’s important to give thanks to where your family comes from, especially if they had to eat each other to get you here.