John Danforth represented Missouri in the U.S. Senate from 1976 to 1995. An ordained Episcopal priest, he officiated Ronald Reagan’s funeral. In 2000, Dick Cheney narrowly edged him out for the vice presidential spot on the Republican presidential ticket. Instead, Danforth went on to serve, briefly, as President Bush’s ambassador to the U.N.

Now 79 years old, Danforth isn’t happy. And, for all his Republican chops, much of that animus is directed at the political right. In his new book, “The Relevance of Religion,” Danforth criticizes a political climate that he sees as overly attached to grand social visions, and deaf to the basic demands of democracy. “The fundamental allegiance of Americans is to our structure of government, not to any particular ideology or policy,” he writes.

Instead, Danforth calls for a kind of ideological disarmament, driven by religious moderates. The basic suggestion here—that religious people can help to make politics more mellow—may sound strange in the era of Hobby Lobby showdowns and Rick Santorum.

But Danforth’s goal is not to amplify the place of religious rhetoric in politics. Instead, it’s to use religious language to insist that politics matters less than the ideologues insist—and that to make a policy position non-negotiable is to turn it into an idol. “Politics,” he writes, “is not the battleground for universal truth.” It’s a process for negotiating compromises.

Over the phone, Danforth spoke with Salon about Ferguson, Donald Trump and whether America still has a conservative political party.

Most Americans would say that they want a friendlier, more positive political dialogue. But things just seem to be getting crazier. What’s the disconnect between our desires here, and what we keep getting?

Well, I think the big question is, “Who is speaking to the politicians?” The most outspoken voices are the so-called bases of the political parties, particularly of the Republican Party. And the message [politicians] are receiving from the base is: “Take an absolute position. Don’t compromise. Be absolutely pure in your position, and if you’re not pure, we’re going to run a primary opponent against you.”

Where have the moderate voices gone?

I think that the great work of America has always been to try to have a process, to try to have a way to hold together all those competing ideas and competing interests. Somehow that process isn’t working now, because people on the edge of politics really don’t want it to work. They want to stay in their absolute positions.

Do you think religious arguments are feeding this divisiveness?

Religion certainly has been divisive. Religion should be a binding, reconciling force in politics. It should make it possible for diverse people to live together in a respectful way.

Some religious communities promote a universalistic vision. But others are pretty tribal.

Robert Putnam and David E. Campbell, in “American Grace,” say that belonging to a religious congregation, regardless of theology and denomination, creates social capital on a broader basis, and connects people to the community around themselves. So, I don’t think that being connected to a congregation necessarily creates an adversarial relationship with the broader community.

You’re an ordained Episcopal priest. The denomination has recently put its weight behind some Democratic policies. Do you ever feel separated from your own movement? What changes when a denomination aligns itself with a political party?

I do think that religion compels us to be concerned about disadvantaged people and poor people. There are a variety of ideas on how to best accomplish that, right across the political spectrum. I think it is a mistake for people to say that the religious position on such-and-such piece of legislation is this or that.

If you say, “I am speaking for my denomination, and my position is the moral position,” does that mean that the opposite position is immoral? How are we supposed to have a meaningful discussion if I am on God’s side and you are on the enemy of God’s side? This shuts it off completely. Politics is not religion. Politics is simply politics. It is a method for working our differences. It is not the realm of the absolute.

Aren’t there cases when legislation does do something immoral?

It is certainly possible. In the days of the Jim Crow, it was a reality.

We should be very wary about saying that somebody’s position on legislation is anti-God. Politics is not saying, “I believe,” as a matter of faith. The way that politics works, when it works, is to engage people with a variety of opinions and competing interests, and hold them together.

When you were in the Senate, how did your religious beliefs inform your politics?

There were a very few instances when I thought there was a close connection between my faith and my view of an issue. I was very interested in world hunger when I was in the Senate. I was opposed to the death penalty, and I thought that had religious implications. But it was not in my mind on a day-to-day basis: “Here is a piece of legislation. What is God’s will in relation to this piece of legislation?”

Religion affects politics in a different way than [offering] direction for positions on legislation. It creates a tone. Part of that tone is honoring the views of other people, even if we disagree with them, and not turning our own position into absolutes—in religious terms, not turning them into idols.

In the book, you emphasize basic, practical changes in the Senate’s culture—like whether or not senators eat dinner with colleagues from the other party.

I had one member of the Senate tell me [recently] that he or she couldn’t think of more than five or six members of the Senate to invite over for dinner. This is a very, very big change over [the] 21 years [since I left the Senate]. My family lived in Washington. We got to know other senators socially. We got to know their children. We were in their homes—Democrats and Republicans, equally.

Part of me hears this and thinks, “In a system with billions of dollars, media empires, and lobbyists, something as simple as dinner is inconsequential.”

I think it is important because it’s one thing that’s practical, that could be done. But the problem is much more extensive than that. Politics is much less workable than it was. There is much greater pressure not to give on anything, to make absolute decisions, not to be working across party lines.

So what would a religious protest against this status quo look like?

I don’t think it takes thousands and thousands of people to pull this off. It would be possible for a relatively small number of people to be much more forceful in presenting an alternative point of view. For example, let’s say that just a few people would make it their business in election terms to attend political meetings, go up to the candidates, and say, “I just saw this commercial. It was run on your behalf. It said you approve this message, and it was a total vilification of your opponent. Tell me how that squares with your values.”

I think pushing against the state of campaigns could definitely be done by people.

In the book, you write that “society is not hopelessly unjust.” There are plenty of critics right now who would disagree. When should people say that they want reconciliation, and when can they say, “The system is never going to serve me. I need to fight against that”?

Reconciliation has to do with mutual respect and humility, and recognizing that politics is always going to be imperfect.

That was the key question for the people who wrote the Constitution. It wasn’t how you were going to come out on a particular issue; in fact, they compromised on the most awful of issues, namely slavery. Their concern was what sort of system will hold us together. That is the thrust of the ministry of reconciliation. It should be the mission of both politics and religion, to try to hold together a diverse nation. But how we do we hold all that together? That is the ministry of the reconciliation. That is the purpose of our Constitution.

Now, when you get to the specifics—what do you think is just or unjust? How does that relate to specific legislation? How do you define justice? What is it? How does it work itself out on, let’s say, healthcare or government spending or whatever else you want to address as a matter of public policy? You can have strong positions on those subjects, and you can advance them as powerfully as you can, but you can also do it within the structure of a system that allows us to state our positions and to be advocates and to press our points, but at the same time do it in a way where the system works.

You’re from St. Louis. One of the messages of the Ferguson protests seemed to be that a lot of Americans don’t feel like the system is working for them, or will ever work for them. What do you say to them?

Well, I say, first of all, let’s listen to you, let’s find out—there is a Ferguson Commission that was appointed by the governor to address just this. What is the path forward? How do we deal with this? They held multiple hearings. They came out with a report. Hopefully, some of that report—some has already been put in place. So let’s address this issue.

Will a committee feel like enough response to people who are protesting?

Well, I certainly would not advocate somehow destroying the system. I would not advocate a situation where all we do is shout down other people.

I would say, okay, what’s the problem? Well, one of the problems here is the situation in North St. Louis County. African-Americans believed that they were being used as ways of financing these tiny little communities. There were traffic fines, and there were just an awful lot of stops of [African-American drivers].

What can we do about that? Well, there was legislation that was passed to try to address that problem. So, okay, let’s figure out where we can effect change, but not undermine the whole system, thinking that will make things better, because it will not.

I’m sympathetic to this idea of a “ministry of reconciliation.” But I’m white and coming from a fairly comfortable background, and that shapes my perspective. How does reconciliation look different, coming from different social vantage points? Is that something you reckon with?

Part of advocacy is to be as effective as you can be, and to be as strong as you can in advocating your position. But at the same time, it’s within a political process. And the political process has a design to create the possibility of change, but to do so within a structure.

This is very much Edmund Burke, who’s one of my heroes. Burke was no conservative with regard to specifics; he was quite a reformer in his day—prison reform and the like. But he also was totally put off and shocked by the French Revolution, and the total collapse of any kind of system in the name of change. He believed in the structure for the management of the country.

That’s the wisdom of conservatism. It’s not the position on this or that—on immigration or something. It’s respect for a traditional system. And I give it that respect, and I don’t think it’s antithetical, in any way, to change.

Over the past couple years, there’s a kind of hopelessness that has become more publicly pronounced on the left, especially in conversations about race. The most prominent writer here is probably Ta-Nehisi Coates, at The Atlantic, who has been asking, What if this never really changes?

Let’s say you take that position. I don’t, but let’s say you do. Then what’s the next sentence? Is the next sentence the French Revolution? I don’t think so. I don’t see the two as connected or disconnected.

Okay, let’s say that you think this is not going to turn out just the way you want it to. So, is that an argument against doing anything? Or do you just go ahead, with the best of your ability?

My view of politics is very realistic, and that is that it’s never going to achieve perfection. That’s not the way it is. Politics is not perfect. It’s just politics.

Is there a place for imagining perfection—for that kind of dream—within American political rhetoric? Or do we need to back off from that?

Perfection is not politics. Politics is legislating. This is a cliché, but legislating is sausage making. That’s the nature of politics. The alternative view of politics is: I know where we should be, and we’re not there, therefore I’m going to shut things down.

I really think that’s the position that is articulated by, let’s say, Ted Cruz, who says, “Look, as recently as last year we won an election. And we have very clear ideas of what must be done. We want to stop illegal immigration, we want to repeal Obamacare, we wanted to defund Planned Parenthood, and now 10 months have passed, and none of that has happened. Therefore, we’re just mad as can be.”

You can hear that on the left, but you can certainly hear it in the Republican Party, also.

Do you think there’s a home for your brand of conservatism within the Republican Party right now?

I think so. I think if it were articulated by a presidential candidate, that candidate would pick up an instant following.

About this business of making America great again, that really is the longing for the man on the white horse. It’s a longing for the powerful individual who will recreate or make the country great. It’s really—it’s dangerous. It’s a dangerous way to look at the country. We’re just going to hope for the superheroes, the Dear Leader who is going to do all this for us, and we recognize from the get-go that that’s not America.

So, are we going to chip away at problems? Yeah. Let’s reach in and move the ball forward best we can, and maybe not move it very much, but at least try. And we are a good country. We’re just a terrific country. And our Constitution is just a brilliant document. Some people who claim they’re constitutional conservatives I think don’t understand the Constitution, because the body of the Constitution is a structure for allowing us to stick together even though we disagree with each other.

Are you surprised to see a figure like Donald Trump do so well right now?

Yeah, I’m absolutely bowled over.

What about his candidacy surprises you?

That there’s an audience for this self-proclaimed great man, and for the anger and hatefulness that he expresses.

Speaking in the sense of Edmund Burke, do you think of politicians like him as conservatives?

No.

So is there a conservative party in this election?

Well, I don’t know yet. I think it’s up for grabs, but I’m concerned about that. We’ll know more in about four months. It could be that there is a right-wing party, but conservative? I don’t see it in the Dems either. I sure don’t see it in Obama.

You know, after the midterm elections, I thought, “Okay, what would I do if I were Obama?” Well, I would never have a meal in the White House without having members of Congress there. I’d invite them up: I’d invite the Dems and the Republicans and the leadership and the members of the Finance and Ways and Means Committees, in selected groups and small groups, for breakfast, lunch and dinner. And the cocktail hour. And I would say, okay, what should we do? What should happen?

But Obama didn’t do that. Talk about my way or the highway. This is not just the problem of Republicans. I don’t see it anywhere.

Critics on the left often accuse Obama of being too compromise-oriented.

Again, the method of going about it is as though there is no Congress. All I’m saying is, this is not just one-sided; I think that there’s a lot of blame to go around. I do think, in my own party, am I troubled? Yes, I sure am. This is nothing to do with what I signed on for. When you think about just really terrific Republican senators, what they were like, like Howard Baker and Bob Dole, it was certainly not “let’s get my way or stop the system.”

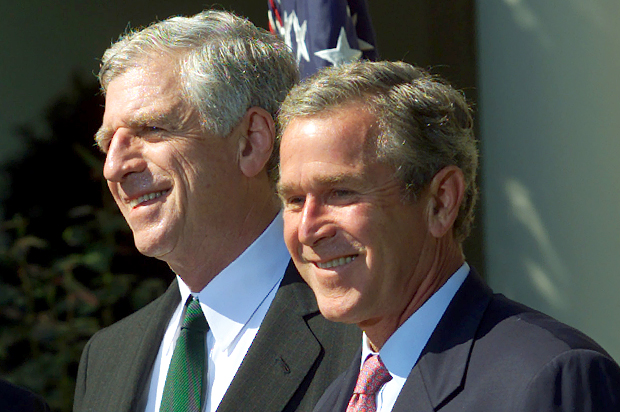

You briefly served in the administration of George W. Bush, who has been described as the most openly religious president in the modern era. Do you think Bush used religion in a conciliatory way—in a way that was consistent with the principles that you lay out in this book?

I don’t see him as being an in-your-face, full-of-himself type. I did not see him as being “Here is my position that’s based on religious principles and therefore, I am entirely right and you’re entirely wrong.

A reporter for the Dallas Morning News, who had covered Bush’s career, said that Bush “believes that he is God’s candidate—that God has chosen him.” Is it healthy for politicians to feel like they have some divine calling behind them?

If you think that “my program is God’s program,” then you’re creating a big problem. Then again, if you think that God empowers you and leads you, to me that’s very meaningful—but that’s a long way from saying that I am the carrier of God’s attempt at this.

Your book focuses on domestic issues, but you’ve been very active in foreign policy, and you served as an ambassador to the U.N. Do you think America sometimes brings a religious vision to foreign policy objectives?

I hope not. Let’s take Sudan, where I was fully involved with George W. Bush. We didn’t have any national interests in that, really. So the pure pragmatists may say what weren’t we doing that way, and did we think we should have been involved? Yeah.

If there was a case like—let’s say starvation in Africa, or something like that, purely humanitarian—should the U.S. be involved? If you see it as a question of values, of course. Religiously motivated values? Yes. It’s a little bit of a departure from the exclusively realist view of foreign policy.

But does the U.S. have a mandate to push itself around the world, and to try to reform the rest of the world into our image? That would be pretentious on our part. It would be lacking in the kind of humility that religion leads us to.

This was certainly a big issue with the war in Iraq, right? The conflict seemed to be framed in terms of good and evil, which quickly gravitated toward accusations that there was a religious element to America’s interventions abroad.

When it comes to Iraq, there surely is [a religious element], yeah. If you’re talking about Sunnis and Shi’ites.

Sure, there was that failure to recognize the textures and complexities of the religious landscape in Iraq. But I mean this in terms of labeling an Axis of Evil, or talking about global conflict in the language of good and evil, which seems to have shaped global perceptions of the war for years afterward.

I think using chemical weapons is pretty darn evil.

OK, so how—

There are all kinds of considerations, you know. We get rid of Saddam Hussein. Then what? That’s a practical consideration. I’m not sure where to draw the line in all this. I don’t think the U.S. is the values arbiter of the rest of the world, and I think there can be things worse than some strongman. It’s just what’s the situation you’re dealing with.

Your book focuses on domestic politics, but this seems to be the other half of the equation: how religion becomes entangled with the image we project abroad.

One of the messages of religion is humility, rather than certainty that you’re God’s agent. That is a message we should carry into foreign policy, as well as domestic.

Looking forward, is there any part of the political landscape where you feel hopeful—where you’re seeing this humility, seeing this search for common ground, seeing this desire to find compromise?

The hope is the American people. I think the American people are different from the way they are represented by politics, and maybe by some activists. I don’t think the American people are hateful. I don’t think the American people are angry. They don’t expect government to be a miracle cure. They simply expect it to function.

Where’s the voice for that? Is the voice all Donald Trump? Or some radio personality?

What they see now is a system where the most demanding people have succeeded in rendering this system into something that doesn’t work. It’s dysfunctional. They would like that changed. And I think that they would be receptive to that kind of voice, if they only were to hear it.

That’s the point of the book. It’s not saying to religious people, shut up. It’s saying, be outspoken—not as advocates necessarily, not that there is God’s position on a particular issue, but rather be outspoken on behalf of this absolutely marvelous system, that was created for us 220 years ago. It’s just marvelous. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t advance it and uphold it.