About the time I reached adolescence, my dad started to disappear. For days at a time. Without explanation. Even when he was around, he was aggressively unavailable. This was tough on my mom, who worked long hours in a psychiatrist’s office, as well as my younger siblings. During those years, the household offered moments of warmth, but mostly alternated between desolation and hostility. I found peace and escape in music.

My first love was Joan Jett. When, as a 10-year-old, I spent most of the spring trapped in a hospital bed with a mysterious inner-ear imbalance, she was there boasting about her bad reputation from the little flip-top turntable on my window ledge. That summer, after my equally mysterious recovery, I was listening to the radio in my own bedroom when KZEW played an episode of the King Biscuit Flower Hour that featured a Joan Jett concert. I cocked my head as Eric “Roscoe” Ambel broke into the opening riff of “Rebel Rebel.” What was this? This wasn’t a Joan Jett song. It brimmed with drama, wrapped its power chords in layers of meaning. Text and subtext. Disenfranchisement and desire. The sound of dirty fingernails. The next day I rode my bike to Half Price Books and Records on McKinney Avenue and paid $3.99 for a battered copy of “Changes One Bowie.”

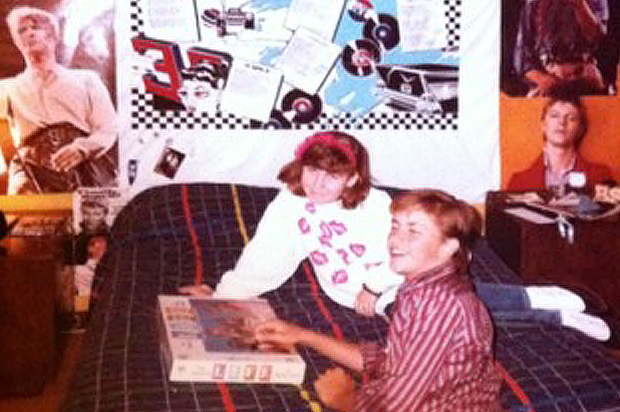

Its iconic black-and-white cover sat propped up in my room for the next handful of years. Before long it felt like a family photograph. This dapper, distinguished gentleman with a twinkle in his eye might be an uncle or an ancestor. He might be my dad. I saved my meager allowance. I stole small sums from my mom’s unattended purse in the dead of night. I rode my bike to Half Price almost every day looking for whatever Bowie albums I could afford and didn’t yet own. I wedged the arm up on my turntable, tricking the device into playing one side of an album on endless repeat. I would sleep that way, side two of “Hunky Dory,” for instance, playing 18 times while I caught my six hours of sleep before another day of school where no one understood me like David Bowie did.

I’d escaped the public school system for what I thought would be the gentler environment of an all-boys private school in Dallas. But cruelty in adolescent boys proved ubiquitous. They told me I was a faggot. They knocked me to the ground, held me down, and whispered it into my ear. I wondered if it was true. I didn’t know what I was. I would sit in my room and study the album cover of the U.S. release of Bowie’s “The Man Who Sold The World.” He looked so beautiful lounging on a chaise with his long hair and his brocade dressing gown. Was I what they said? I decided that I was different from them regardless of whom I wound up wanting to sleep with. They were mundane and ignorant. I had so much more in common with this bold, strange artist to whom I devoted so many hours.

I took up the guitar. I learned to play his songs. I began to write my own songs. I became an acolyte, soaking up Bowie’s catalog and following the splintering trails off into his influences. My identity became ever more tied up in that of my hero. He was my secret guide through this wilderness, his music my personal handbook for survival.

And then he released “Let’s Dance.” This artist from the 1970s, whose records I’d dug out of dusty bins in second-hand shops, was suddenly wall-to-wall on the nascent MTV network. He was all over the radio. He was drifting out of overhead speakers in Safeway supermarket and Northpark Mall. I remember hiding in the bathroom at a seventh grade back-to-school mixer after Marla Cotton’s new boyfriend, a tight end on the JV squad at another school, had announced upon arrival that his whole purpose in coming to Bent Tree Country Club that night was to find me and “kick that little faggot’s ass.” I’d called my mom and begged her to come pick me up, but there would be a half hour before she could rescue me. When Marla’s new boyfriend finally did find me, in a stall in the men’s room off the ballroom’s foyer, he cornered me. Literally. He planted his palm on my forehead and pushed the back of my head into the tiled corner, muttering in his impossibly low voice, “You like that, you little faggot?” The chipper keyboard stabs of “Modern Love” wafted in from the ballroom, and cut through the buzzing in my ears.

The fact that this new Bowie belonged to everyone complicated my relationship to his body of work but didn’t diminish it. “Yeah. It’s cool,” I’d say. “But I’m really into his older stuff.” When the Serious Moonlight Tour rolled through Dallas’s Reunion Arena, my girlfriend’s big sister got us tickets. Our seats were in the lower bowl, directly stage left. We watched the show through the rigging, looking at the band in profile. I thrilled with anticipation as each song drew to a close. I imagined him constructing the setlist, testing the audience with new album tracks and deep cuts, rewarding the audience with old favorites and the hits that currently owned the airwaves. I clearly saw what he was doing that night as a job, with logistics and strategies and responsibilities.

Toward the end of that night’s concert, during the break between the main body of the set and the encore, the band ran off stage right and Bowie slipped off stage left, descending a few steps down a short flight of stairs behind a massive column of speakers directly in front of us. I watched from 75 feet away as a crewmember handed Bowie a towel and a lit cigarette. Another member of his crew placed a sweaty highball glass on the railing next to him. My idol stood alone for a moment, a towel around the shoulders of his soft yellow suit, a cigarette dangling from his lips. He pressed the icy highball glass to his forehead. Seventeen thousand people chanted his surname, a mantra, an invocation. As the adulation built to a frenzy around him, he took a quiet moment to himself. I watched him, and, in that moment, discovered something about myself: I wanted that job.

After that, everything I did was toward that end. I wrote songs constantly, pushing through the terrible ones to get to the merely bad, knowing experience was the only way to improvement. I went to underground rock clubs and made friends with the musicians. I did my first gig at 15 and recorded my first album at 17. On that album, I covered an obscure Bowie tune called “When I’m Five,” a song he’d written in the late 1960s, sung from the perspective of a 4-year-old boy. Despite being a seventh-generation Texan, I sang that song and all the others on that album with a hint of a British accent. I kept going. Through poverty and squalor. Past obstacles and heartbreak. I kept going. I saw my path. I followed my North Star, Bowie.

And I wound up making a life out of music. I write songs, and travel the world singing them for people. I stand on the side of the stage mopping my brow while the audience calls me back for an encore.

I’ve been lucky enough to meet and even work with many of my heroes. But I never met Bowie. I have a friend who for years encouraged me to write a letter to David Bowie in the hopes of collaborating with him. My friend could guarantee that someone in his inner circle would deliver the letter, along with a glowing recommendation, to Bowie. I wrote the letter in my head a million times, but never committed it to paper. I think I was afraid to lose him. I love what he gave me, who he is in my life. What if that changed somehow? Rejection, disappointment, who knows? A human can’t really be a North Star, can they? I couldn’t stomach the possibility of life without David Bowie.

And then I did lose him. We all did.

But I look up in the sky and I see him.

And I hear him in my head.

And I always will.