If you’ve followed any of the headlines emerging about the “comfort women” in the past weeks—or months, or years, or decades—you probably have some questions. Did the Japanese government really coerce thousands of women into military brothels while its empire colonized Asia? Were the so-called “comfort women” sexual slaves or indentured servants, consenting prostitutes, or none of the above? Was the Japanese government’s recent apology to South Korea, along with the pledge to pay $8.3 million to Korean survivors, a resolution, an insult or one step in a long process of reconciliation? Does the U.S. bear any responsibility? And why is a statue of a teenage girl still making so many people so mad?

The answer to each is, “It’s complicated.” Like most matters of history, especially those entwined with violent colonialism, there are heaps of good questions, but few simple ones. Still, the story of the comfort women and the issue’s legacy today is worth your interest. There are plenty of books to help readers untangle the thorny topic. From the researched to the riveting, here’s a glimpse into the long overlooked literature of the comfort women.

“Comfort Woman, A Novel,” by Nora Okja Keller.

If you’re going to pick up just one book about the comfort women, this should be the one. It is hands down the best piece of fiction on the topic written in English.

There’s an old concept in Korean culture called han. It has no English translation, but is often imagined as a knot growing in a person’s chest until it’s too big to remove. Han describes bitter sorrow laced with hope for things to improve, and the simultaneous recognition that they will not. This beautiful book is full of han.

Okja Keller’s book interweaves two stories. The first is the life of a Korean girl who ends up in a comfort station, where she is given a new name, and reduced to an amenity for Japanese troops. She survives, thanks to the unsettling help of a zealous U.S. missionary, and immigrates to Hawaii. The book alternates between her and the perspective of her adult daughter. Both struggle to understand each other.

The mother’s plot is partly based on the real-life testimony of comfort station survivor Jok Gan Bae and includes the story of Princess Pari, the legendary character of Korean folklore who escaped from hell to become the first female shaman.

I taught this book to a class of undergraduates in a required literature class at a Virginia university. Worried I was only assigning it out of personal interest, I thought they’d dislike it. I was wrong. Despite endless stories about coddled college students who refuse exposure to the unpleasant, my students craved this book’s honest portrayal of the troubling and the heartening. One of my students grew up in Thailand and had never finished a book. She finished this one. Others were first generation Korean students who had only heard bits and pieces about the comfort stations. Many were wealthy white males with conservative dispositions. It didn’t matter. None could abide the horrible acts of too many people in the book, and all of them wanted to read more.

For most of my students this book was the most revelatory thing they read all semester. And I shouldn’t have been surprised. Lyrically written, with memorable characters who are both heartening and disturbing, its themes are the same our current culture is wrapped up in: first generation immigrant experiences, hypocritical religious zealotry, gender identity, the politics of our bodies, and the many elements that converge so we keep secrets about what happens to them.

“Comfort Woman: A Filipina’s Story of Prostitution and Slavery Under the Japanese Military,“ by Maria Rosa Henson.

This is one of the few autobiographies written by comfort station survivors. In it, Maria Rosa Henson tells the story of her life in the Philippines and her internment as a comfort woman. It’s a slim book, sprinkled with family photos and Henson’s drawings, so it’s an easy, one-bath read. But sometimes watching her life unfold is so overwhelming, that I took my time reading. At the age of 15 Henson was forced to become a sexual slave to the Japanese soldiers who occupied her Filipino town. The same soldiers visit her every day, becoming characters in this book. One shows her kindness, and they have a relationship of sorts, but all the while he too exploits her. Henson is an amateur writer, but her frankness in relaying the events of her life is staggering, and she has a knack for including specific details that stick with you. In one passage Henson is confronting memories she couldn’t share. “Whenever I felt the need to talk, I would write instead on small sheets of paper, ‘Japanese soldiers raped me. They fell in line to rape me.’ Then I would crumple the paper and throw it away.” Henson has since died, but written across the pages of this book is her refusal to be discarded.

“True Stories of the Korean Comfort Women,“ edited by Keith Howard, compiled by the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery.

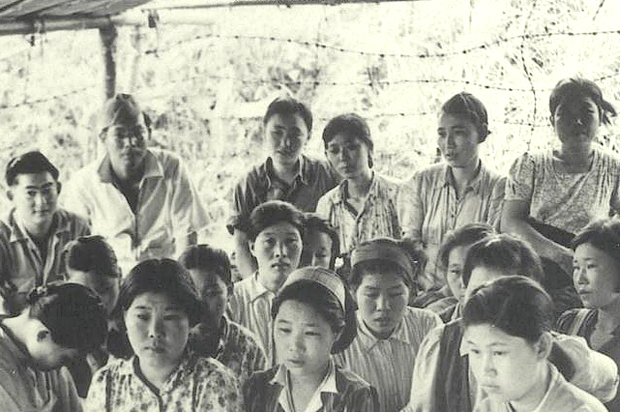

Perhaps the only reason the “comfort women” are discussed today is the work of a few key activists who grew from South Korea’s burgeoning women’s movement in the ’80s. They were part of a larger push to include the experiences of women in public memory. One of those awareness-raising groups, the Korean Council for the Women Drafted into Military Sexual Slavery by Japan (not the most efficient name, but direct), set about recording the oral testimony of comfort station survivors from Korea. They conducted extensive interviews. The women were elderly and most had rarely discussed what they survived. The result is this collection of 20 interviews. Sometimes the women’s memories seem foggy; others come across with painful clarity; but overall they make it clear why this is an issue worth investigating.

“Comfort Women,” by Yoshimi Yoshiaki, translated by Suzanne O’Brien.

I’ll be the first to admit that book is not the most dazzling literary journey you’ll ever travel. It’s the work of a scholar, and feels like it. But if you are the kind of reader who can nerd out on impressive research, then this deep-dive will speak to you. As a young man in Japan, Yoshimi Yoshiaki joined a group of professors who argued that investigating the past, good and bad, was crucial for the nation’s health. One day while rooting through Japanese military archives he came across evidence that the government had supervised a vast system of military brothels for its troops, and was well aware many of the women in them were coerced. This was big news, and set off a chain of events that uncovered stacks more evidence. Yoshimi doesn’t rely much on the testimony of survivors. He’s more interested in troop diaries and government records. He also addresses how the Allied forces, including the U.S., were aware of the exploitation in the comfort stations, and even used the system after winning the war.

“The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan,” by C. Sarah Soh.

Here’s the thing with books about the comfort women: Their titles don’t vary much, so this one has the same name as all the rest. But it has a unique perspective. Activists sometimes present a monolithic story of the comfort women, implying each was kidnapped, imprisoned and forced to provides sexual services without pay. It’s a response to neoconservatives who have denied the comfort stations existed at all, or that anything criminal happened in them. As a result, the diverse spectrum of individual experiences, and the personality of the people behind them, can feel lost. Soh counters that monolithic version in this book, which discusses the range of conditions women encountered, and tackles head-on whether people who collaborated with the Japanese contributed to the suffering of their own countries. This month another Korean author was accused of being a “pro-Japanese traitor” and found guilty of defamation for similar claims. It’s the sort of honesty that makes people uncomfortable, but it’s brave too.