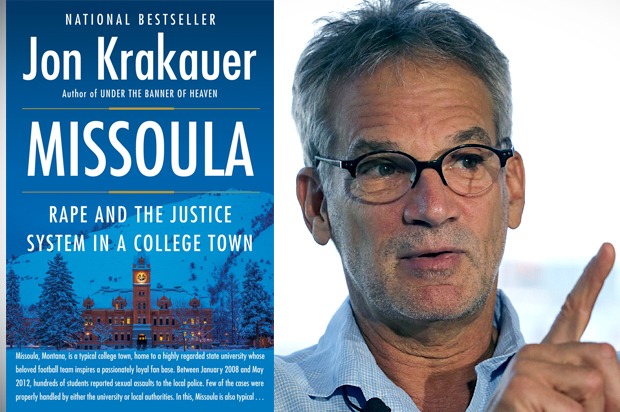

Jon Krakauer released his latest book, “Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town,” in April of 2015, in the midst of a multi-year resurgence of interest in the topic of acquaintance rape and efforts to reduce its incidence, especially on college campuses.

The book examines the issue through the lens of one small college town in Montana, a place that is notable mostly for how typical it is of college towns, all of which struggle with this problem on some level.

I interviewed Krakauer shortly before the release of the book in paperback recently to get his thoughts on the prevalence of rape, the debate over false accusations and how to fix the problem of rape culture. The text below is an edited version of our conversation.

Sexual assault, especially among people in their teens and 20s is, unfortunately, a really common crime around the country, so why did you make the book about Missoula, which is a small town in Montana?

It is. Although it is the second largest city in Montana. I wrote this book for very personal reasons. This young woman, who was very close to me, I learned she was raped and suffered decades of trauma and her life kind of blew up.

I started just researching the subject and I started following cases, about 30 cases around the country, and one of them happened in Missoula, and that is just a coincidence, that I came across a case that I was going to build a whole book around, the Allison Huguet case. Once I picked Missoula, I thought it was actually a really good place to write about because it was typical. It’s not an outlier; its problems are probably less than most cities and they’re handled better but it was still appalling to me. Missoula is a pretty accurate representation of the national problem.

The University of Montana is in Missoula and the complaints about that school kicked off the national conversation about sexual assault. Have you read the report that the Department of Justice did on the University of Montana and the policy agreement that they came up with? What did you think of it?

Montana, actually for the most part, handled rape cases much better than most schools, significantly better. And it’s still appalling. But the remedies, I don’t think…it’s been a while since I read that agreement but I don’t think they go far enough.

A much better step that has been taken is the bill that Senator Kirsten Gillibrand is trying to get through the Senate to make this a national, a sort of uniform national policy. Because until that happens, the University of Montana can make great improvements, but if it’s just one school that’s not going to fix it.

If you go school by school it’s never going to be fixed. You know, I get really pissed off at this argument, “Oh, this is too serious a crime. Universities shouldn’t even adjudicate rape, they should turn it over to the police.” Well, the criminal justice system, with its high burden of proof, will never address the problem adequately. And universities, by Title IX, are required to do something about it.

And it seems like a false choice to me. A lot of the cases in your book show victims that reported to both law enforcement and to the university.

That’s right and only a small percentage of criminal cases ever get prosecuted, for reasons I talk about in the book. The cases I wrote about in my book, except for the Jordan Johnson case, were handled well by the university, but that wasn’t because the university had a great system particularly, it’s because they had a really committed dean of students, Charles Couture. Unfortunately he retired. If a system depends on one person, like one good or bad dean, that’s not a good system. That’s why I think Gillibrand’s bill is important.

Why is it so hard, do you think? Even in the 21st century, when we claim to take this crime so seriously, it’s hard for victims of sexual assault to get justice or even just to get their assailant expelled from school.

There’s this deeply rooted belief in the male dominated world that women lie about rape. They don’t necessarily lie about other things but there’s this deeply entrenched myth that women lie about rape.

False accusations of rape are pretty much the same as any other serious crime, yet we treat rape completely differently. In rape we assume that the accuser is lying, you don’t assume that when your stereo is stolen from your car but we do about rape.

I’m concerned about false accusations. It’s terrible when someone goes to prison for being falsely accused of rape and there are definitely people in prison who don’t belong there, but the number of men who are in prison who have been falsely accused is a tiny fraction of the number of women who are raped and their rapist was not held accountable. The much larger problem is rapists who get away with it, not men who are falsely accused. That’s something that persists, and I run into over and over again, people just don’t seem to be able to get that.

One thing that you say in the book that I thought was interesting was that the two goals — reducing rape and making sure that men are not falsely imprisoned — can actually work together and are not at odds at all.

I think you’re right about that. If you do a good investigation you want to find out what happened. And that’s one mission, it’s not like one or the other. You’re trying to figure out the truth. That’s hard to do in rape cases and it’s hard to do in any crime.

You start out by listening to the victim. You don’t ask tough questions like, “What were you wearing?” or “Do you have a boyfriend?” You just listen, and you get all the information you can, because trauma affects memory.

There’s good science to show that trauma affects the way the victim is going to tell their story, so your job as a prosecutor, or a journalist, or anyone else is to just let them talk, let them just free associate what they remember, what they felt. Then once you have that, then you can start trying to corroborate it, and that works really well in my experience. The cops, the detectives I talked to, a lot of them, once they’re introduced to that sort of way of interrogating, way of investigating, they see the error of their old ways and are grateful for the change.

Your book was hard to read, but one part that gave me a lot of hope was the Allison Huguet story, which you build the book around. In your recounting of it, Allison viewed what happened to her as rape from the minute that it happened. Are young women just smarter about these things?

I think they’re getting smarter. When you start looking at rape cases, women never say, “I was raped,” like Alison. They say, “Oh my God, I’ve been raped? Was that rape?” Their first reaction is doubt, and I don’t know how you change that. Because that’s not so much cultural, as psychological, that’s brain chemistry. You cannot face, that, “Oh my God, I was just raped!” So you question it.

And of course that works against a victim. As soon as she goes to law enforcement or whoever investigated it, they say, “Wait a minute, you’re not even sure you were raped? How are we going to get a conviction?” When in fact the psychology shows that that’s the most common way women do react.

I don’t know when things started to change. It was maybe starting when I was in college in the ’70s, but it’s definitely in the last five or 10 years. More and more women are saying, “Fuck it, I have nothing to be ashamed about! The fucker who raped me is the guy who should be ashamed. I’m going to use my name, I’m going to come forward.”

With my book, initially I assumed all the women would want to have pseudonyms. In every case, including Alison’s, I tried to talk them out of using their real names, and in every case for each of the women I interviewed, they all came to me and said, “No, I want you to use my real name.” I’m proud of them for doing that, but I didn’t want that responsibility. So I’m like “no,” and they’re like “yes.” And that’s a sign that stuff is changing, and that’s what it takes.

Silence and alcohol are the main weapons perpetrators use to get away with rape. It’s not knives and guns. It’s silence and alcohol. And the silence is something the women can do something about, if they’re willing to pay the price.

I’ve gotten messages from women who have said, “You know it’s great, I admire these women, but they’re still going to pay a price and they’re still not going to be believed by most people and they’re going to be ostracized and slut-shamed.” And that’s all true. You’re still going to pay the price, but that’s what’s so courageous about it.