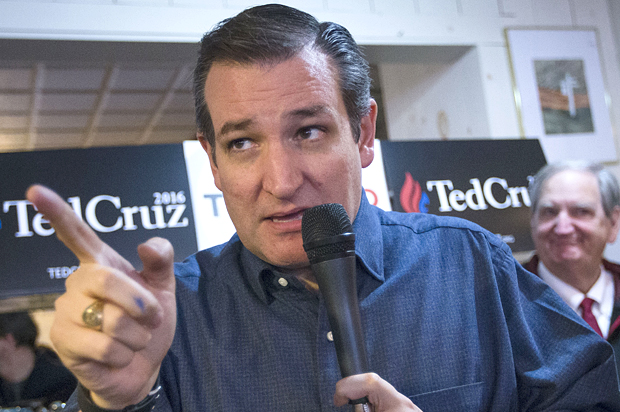

It appears that those who live by the sword of constitutional originalism may be destined to perish by its two edged blade—or maybe not. Is Ted Cruz a “natural born citizen” under the U.S. Constitution and hence entitled to run for the president? Editorialists, pundits, constitutional law professors, and yes Donald Trump, have all weighed in on this question. The emerging consensus appears to be –well– that depends on your preferred theory of constitutional interpretation. If you support the idea of a living or an evolving constitution, or even if your support the pluralist methods favored by most modern judges, Cruz clearly meets the constitutional requirements for becoming president. Originalism, by contrast, the theory Cruz himself favors, offers the strongest arguments against his eligibility.

To date efforts to defend Cruz in originalist terms have not been especially effective. In a short article in the Harvard Law Review, Neil Katyal and Paul Clement, each a former solicitor general of the United States, argue in broadly originalist terms that Cruz is eligible. Neither Katyal nor Clement have strong originalist credentials, but they are two of the most effective Supreme Court litigators and their arguments are therefore less academic and more attuned to the type of originalist arguments likely to be persuasive in court.

These two “super” lawyers point to a series of statutes enacted by the British Parliament before the American Revolution as a key to unlock the meaning of this contested provision of the Constitution. It is true that Parliament extended the rights of natural born subjects to children born abroad to parents who were English subjects. The problem for Cruz is that these laws only extended these rights to children whose father was a natural born subject. Given that Cruz claims American citizenship by virtue of his mother, not his father; he would not have been a natural born citizen under that definition.

A cleverer originalist argument has recently been floated that focuses on Parliament’s authority to change the English common law definition of natural born citizen, something it did several times in two centuries before the American Revolution. If one assumes that the Founding generation believed that Constitution gave Congress similar power under its authority to establish uniform rules of naturalization, Cruz is in good shape, even under an originalist model. If this were true and the term “natural born citizen” was something Congress could re-define as it wishes Cruz might still be able to have his originalist cake and eat it at the Republican national convention.

One of the problems this theory must overcome is the obvious differences between the scope of the British Parliament’s authority in the 18th century and the far more limited nature of the powers vested in Congress. Britain’s Parliament was omnipotent, Congress was limited by the text of the Constitution. Although ingenious, this type of originalist argument requires a good deal more historical evidence to prove that this understanding was wide spread in the Founding era. It would mean that Framers of the Constitution used a technical legal term borrowed from English law, but gave Congress the power to change its meaning.

There are several reasons to doubt that this was the case. One of the key texts cited by everyone in this debate, including Katyal and Clement, is the first naturalization act passed by Congress in 1790. Courts have always assumed that the First Congress was uniquely positioned to interpret the meaning of the new Constitution. The language of that 1790 text asserts that “the children of citizens of the United States, that may be born beyond the sea, or out of the limits of the United States, shall be considered as natural born citizens: Provided, that the right of citizenship shall not descend to persons whose fathers have never been resident in the United States.”

According to Katyal and Clement, “The Naturalization Act of 1790” expanded the class of citizens at birth to include children born abroad of citizen mothers as long as the father had at least been resident in the United States at some point.” While this reading may be plausible when read against the assumptions and interpretive conventions governing modern law, it seems highly improbable that the First Congress or the vast majority of lawyers or judges in the early Republic would have come to the same conclusion. A much more historically attuned reading of the text would be that the First Congress took the accepted notion of natural born citizenship already articulated in English law which was based on the status of ones’ father and added an additional and more stringent requirement that one’s father also had to have been resident in the US. There is almost no contemporary evidence to support Katyal and Clement’s feminist reading of the text, appealing as it may be to modern ideas of gender equality.

There is another problem with the feminist reading of the naturalization act of 1790. Katyal and Clement note that the Founding generation was deeply influenced by Sir William Blackstone, but they curiously ignore the learned English judge’s comments on the legal status of married woman. “By marriage, the husband and wife are one person in the law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband: under whose wing, protection, and cover, she performs every thing.” When an analogous issue about a woman’s freedom to reject her husband’s national allegiance came before American courts a decade later, the Blackstonian notion prevailed. Apart from the most heinous crimes such as murder or treason, it was generally assumed that a woman’s choices were not her own to make. To accept Katyal and Clement’s view of the Naturalization Act one would have to believe that the First Congress not only broke with pre-existing English law, but that they struck a major blow for woman’s rights which went un-noticed by any contemporary commentator, including some of the nation’s leading jurists.

Ted Cruz is not the first presidential candidate to face a conflict between his political objectives and his constitutional theory. Thomas Jefferson was in much the same position when he cast aside his theory of strict construction and decided to purchase Louisiana from the French. There are no serious legal obstacles to Cruz moving forward. The only question is will he show some measure of intellectual integrity and reassess his commitment to originalism. The Founding generation was steeped in Roman republican values and Cruz ought to take a lesson from them.

Ted Cruz can keep his constitutional ideas and fall on his originalist sword by abandoning his quest for the presidency, or he can admit that the theory he has championed for so long simply does not make sense in this day and age. Most likely, he will try to have it both ways, a craven form of political pandering, and something that would have disappointed leading members of the Founding generation.