There have already been so many incarnations of Donald Trump in this election cycle. From the day he entered the race there was the racist Trump, followed by the misogynistic Trump after the first debate. Terror attacks launched the xenophobic Trump — essentially Islamophobic, though nicely balanced with a strain of anti-Semitism that surfaced at a Jewish event. The boorish, megalomaniac, plutocratic persona has pervaded all these shades of Trump, alongside Trump the bully, Trump the ham, and so on.

Still, there are untapped depths of Trumpery that have not yet surfaced in the media avalanche. They emanate not precisely from “Trump” the man, but “trump” the word. And while such resonances may seem like accidental connotations, or merely English-professor cleverness, I would suggest that we actually hear these aspects, perhaps as subliminal undertones, as we suffer through this interminable bombardment of all things Trump. Like many of my fellow Americans, I wish it would all just go away — but since it won’t, I might as well join in.

Let us consider, then, one more dimension, the final frontier: Trump the aptronym.

An aptronym (yes, it’s a real word) is “a proper name that aptly describes the occupation or character of the person.” As an uncommon phenomenon, it’s all the more striking when it occurs.

The aptronymic character is a literary staple, sometimes referred to as a “Dickensian name” (think of Scrooge, Pecksniff, Mr. Sloppy, Mr. Bumble). Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the 18th-century English playwright, was also fond of them: his play The School for Scandal features Sir Benjamin Backbite, Lady Sneerwell and Mr. Snake.

Real life, too, offers up such aptly-named figures every so often. Think of world champion sprinter Usain Bolt, George McGovern (who failed in his 1972 campaign to govern the U.S.), and, back to literature, sublime Romantic poet William Wordsworth. If Bolt’s and Wordsworth’s names illuminate their virtues, other aptronyms may highlight less salubrious characteristics: Dennis Rodman’s father, Philander Rodman, is reported to have sired 29 children by 16 mothers. Thomas Crapper was an early innovator in the toilet business. And who can forget the sexting scandal that erupted from Anthony’s Weiner?

If you go back far enough in the Butcher family, you’ll find a butcher, and in the Goldsmith’s you’ll find a goldsmith. I come by my aptronymic expertise honestly: My own name, “Malamud,” is a variant of the Yiddish word melamed, teacher, which is in fact what I am. A distant ancestor must have been as well.

My father is also a teacher – is it possible that names are destiny? Scientific journalist John Hoyland believed they might be, coining the term nominative determinism to describe people’s tendencies to enter “apt” professions: he cites as examples a jurist named Judge and an Arctic specialist named Snowman.

Despite all the reasons Trump deserves America’s disdain, I want to give credit where it is due and acknowledge that he is the best named candidate in the race. (A quick shout-out to Rick Santorum, the subject of Dan Savage’s brilliant postmodern double-reverse aptronymic ambush. In 2003 Savage found then-Senator Santorum’s politics so homophobic that he held a contest to invent a neologism that would reflect the ignominy he felt the politician deserved. The winner — “the frothy mixture of lube and fecal matter that is sometimes the byproduct of anal sex” — managed to displace Santorum’s actual website as the top Internet search result.)

Trump himself is obviously aware of his name’s brand appeal, its snazzy impact, its larger than life iconic allure, as he has stamped it all over his buildings, planes, resorts, fashion collections, and golf courses.

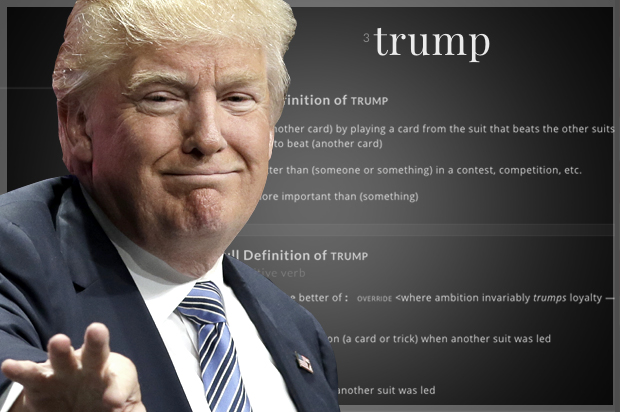

So what exactly does trump mean? As early as the sixteenth century, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word described “a playing-card of that suit which for the time being ranks above the other three, so that any one such card can ‘take’ any card of another suit.” The trump card irregularly acquires a power that it doesn’t normally inherently have. That’s a pretty fitting metaphor for what Trump has done to the Republican primary contest, isn’t it? He has trumped the political aces and kings. Jokers are commonly trumps, and I’d say this year the converse is true: Trump is a joker.

The word “trump” evokes images of a strong, successful player, a winner: to “turn up trumps” is to turn out well or successfully. In Australian slang, the trump is the person in charge. But there are less salubrious meanings, as well, bringing out the seamy underside of the wealth and power that accompany the person who holds the winning hand. Something that’s “trumped up” is unscrupulous, forged, fabricated. Ben Jonson’s 1629 play The New Inn warns that dame Fortune “is pleas’d to trick or trompe mankind,” meaning to deceive or cheat. Shakespeare used the word “trumpery” to denote a trifle, something of less value than it seemed. Now, I think, we’re hot on the trail of Donald’s inner trump.

Trump is etymologically related to “trumpet,” which gives rise to my favorite usage, an obscure and archaic definition buried deep down in the dictionary trump-roll, but one that I fervently hope to upvote so that we think of it every time Trump trumps his way into the spotlight.

Like Savage’s Santorum, this trump emanates from the asshole: In 1903, the word was recorded in a compendium of slang, signifying “the act of breaking wind audibly.” I offer this as my own small contribution to this year’s political discourse. Every time Donald Trump opens his mouth, let’s hear, instead of his demagogic blather, this etymological gem: the bung blast, the rump ripper, that trumps his tricky bravado and captures his essence.

Randy Malamud is Regents’ Professor of English at Georgia State University.