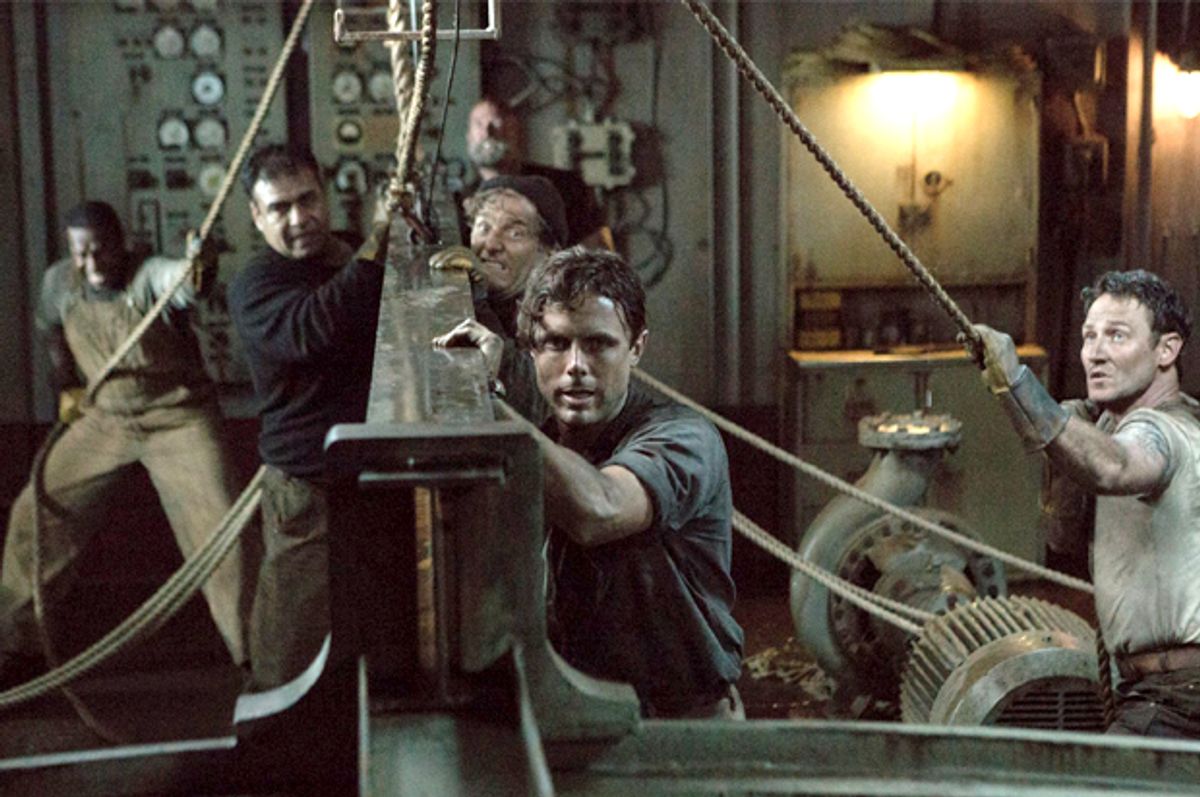

In the book turned Disney action movie ‘The Finest Hours," due out Jan. 29, Chris Pine plays real-life Coast Guard hero Bernie Webber. In February 1952 Webber and his crew of three saved 32 of 33 sailors trapped on the stern end of the Pendleton, a ship that split in two during a historic storm off New England. The Pendleton was one of two war-surplus tankers that were torn asunder by the monster storm’s 40-60-foot waves. Webber’s seamanship running his 36-foot motor lifeboat through snow-blown surf and making a near impossible rescue quickly earned him a place in the annals of gold-medal lifesaving.

Still, his rescue is just one of many in Coast Guard history. Its ranks of heroes who’ve pulled off similar amazing feats range from Alaska’s "Hell Roaring" Mike Healy to North Carolina’s Rasmus Midgett and Richard Etheridge to Rhode Island Lighthouse keeper Ida Lewis to the aviators and small boat crews who surged into New Orleans and the Gulf Coast following 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, saving 33,000 lives.

What sets Bernie Webber apart is that when his dangerously overloaded boat was filled to the gunnels with freezing men and ocean water and his superiors were radioing contradictory orders on where he should head and what he should do next he reached over and switched off the radio that was distracting him. This guaranteed his status as an enduring hero for generations of enlisted men and women.

Years later I interviewed another small boat operator who during a giant fireworks display on San Francisco Bay messed with a radio transmission from a superior who refused to believe he’d seen what he saw drifting behind a curtain of smoke. He and his crew then dashed into the choking ember-filled blast zone to rescue a couple and their two small children whose broken down motorboat was by then smoking and about to catch fire. Afterward he recalled, despite the applause of thousands of spectators on shore, “The patrol commander said, ‘Your ass is mine,’ and tried to bring charges against me, but my captain said, ‘Don't worry about it,’ so I didn’t.”

When I was working on my book "Rescue Warriors: The U.S. Coast Guard, America’s Forgotten Heroes,” one of the things that most impressed me about this smallest of the armed services, with just over 43,000 active duty and reserve members, was how far down the chain of command they push leadership and on-scene initiative. Part of this is based on necessity given how many of their Search and Rescue (SAR) and other missions are carried out by enlisted personnel who are forced to make critical calls in difficult and unpredictable water conditions.

Given its small size and historic underfunding, having its enlisted take on command authority at a level not seen in the other services also acts as a force multiplier. Many of the service’s elite jobs, including Rescue Swimmer, small boat "Surfman," Tactical Law Enforcement and polar diver, are reserved for enlisted ranks who also get to command the Coast Guard’s swimmer shops, surf stations, patrol boats and river tenders.

An enlisted chief who ran a Coast Guard tug in New York and had previously served in the Army told me, “As an [Army] E-4 I’d have to ask four people and get signatures to take a Humvee out to pick up a FedEx box. In the Coast Guard as an enlisted E-4 I would take out a 47-foot surfboat without calling anyone. There’s that much difference in bureaucracy, or at least in trust.”

“The enlisted in the Coast Guard are a lot more empowered than in the other services,” agrees a former Marine who became a senior chief overseeing the Rescue Swimmer School. “In the Marines you don’t move till you’re told to; here they expect you to figure it out – and go get it done. Lots of prior-service guys will first wait for an order and then realize it’s not coming. They [the Coast Guard leadership] expect you to be a self-starter. They have faith in their people. What’s so cool is we have this latitude to initiate commonsense action, and if what you do is based on good order and discipline, no one flips out when you do it.”

A classic example of how this works in practice is the story of Chief Warrant Officer (CWO) David Lewald. A CWO is an up-from-the-ranks hybrid position between the enlisted troops and commissioned officers. The day after Hurricane Katrina made landfall in 2005, Lewald led a flotilla of small boats and construction tenders down the Mississippi from the “hurricane hole” they’d taken refuge in during the storm. Powering into the devastated city of New Orleans, he began telling his sector command in Alexandria, Louisiana, about the levees having been breached and the city flooded when he lost radio and cellphone contact. It would be more than three days before a 270-foot Coast Guard cutter came up river from the Gulf with officers onboard. In the interim Lewald and his enlisted crews set up a command post and security perimeter, rescued and treated hundreds of sick, wounded and dying people, coordinated with the locals, and helped evacuate 6,600 people across the river from their flooded homes. He was then piped aboard the cutter and taken to its air-conditioned Combat Information Center where the ship’s captain smiled and asked, “So what can I do for you?”

Of course, up from below leadership like that only works when the highest standards of training and oversight are maintained. And even then the burden of command can impose painful emotional scars on mostly young enlisted women and men asked to make spur-of-the-moment life and death decisions. Today post-traumatic stress disorder is better understood and treated than it was in years past.

Although 24-year-old Bosun’s Mate First Class Bernie Webber rescued 32 men on the night of Feb. 18, 1952, he was unable to save Tiny Myers, the Pendleton’s 350-pound cook who jumped too soon and was crushed between the rescue boat and the Pendleton’s propeller blades. While it was an unavoidable moment in a horrific maelstrom Tiny Myers' death would haunt Bernie Webber for the rest of his days.

David Helvarg is an author and executive director of Blue Frontier, an ocean conservation group. His books include "Rescue Warriors" and "Saved by the Sea," both now in paperback.

Shares