Whenever people ask where I get ideas for my thrillers, I say, “Direct from the U.S. government.”

They laugh, but it’s true—in a time of detention (indefinite imprisonment without charge, trial or conviction); enhanced interrogation (torture); targeted killings (extrajudicial assassinations); and, of course, the unprecedented bulk surveillance revealed by whistle-blower Edward Snowden, third-party villains like SMERSH and SPECTRE and the rest can feel a bit beside the point. Indeed, when the NSA, in its own leaked slides, announces its determination to “Collect it All,” “Process it All,” “Exploit it All,” “Partner it All,” “Sniff it All” and, ultimately, “Know it All,” it’s safe to say we’re living in an age of “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”

Does that claim sound extreme? Have a look at this National Reconnaissance mission patch. What is this Octopus doing to the earth?

There are two things worth noting here. First, a giant octopus strangling, eating and/or otherwise assaulting the earth is how our intelligence apparatus (which prefers the friendlier nomenclature “intelligence community”) perceives itself. Second, that apparatus has become so detached and unaccountable that it now believes this kind of logo will create a favorable impression among ordinary people.

Naturally, there are dozens of other such patches from various intelligence and military organizations, many of them incorporating figures like poisonous snakes and devils and even the Grim Reaper, variously clutching, encircling and attacking the earth. In fact, Trevor Paglen has written a whole book on the topic: “I Could Tell You but Then You Would Have to Be Destroyed by Me: Emblems From the Pentagon’s Black World.” The imagery and slogans offer a fascinating look at the leaking id of our metastasized national security state; if you’re curious, here are a few links with many more.

As a certified news junkie and civil liberties and anti-torture activist, I’ve long been aware of these patches, along with some of the examples of governmental overreach the patches tend to suggest. After all, New York Times journalist James Risen broke an early NSA domestic spying story all the way back in 2005. So I’d been playing around with a novel based on a top-secret government surveillance program for quite a few years when the Snowden revelations shocked the world in the summer of 2013. I thought, Hmmm, powerful actors doing terrible things for reasons they believe are good—my kind of villainy!

So I obsessed over the news articles. I imagined what wasn’t being reported—what even Snowden might not have been able to access. And I remembered one of the things they taught me at the CIA: that sometimes it pays to cover up the commission of a serious crime by confessing to a lesser one. The programs Snowden revealed were appalling, yes, but what would be the even worse ones, the ones that would leak later, if at all?

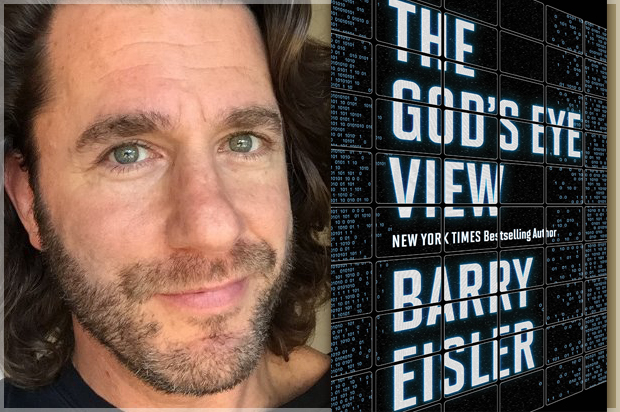

My answer to that question—informed by the abuses of the J. Edgar Hoover years, the history of COINTELPRO, the allegations of NSA whistle-blower Russ Tice, and most of all by Snowden’s revelations themselves—became the foundation for “The God’s Eye View,” with an all-seeing surveillance state the novel’s milieu. In fact, Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon—the circular prison in which a central watchtower would simultaneously monitor all the prisoners—became a kind of motif for the novel.

Within that framework, characters began to evolve. I asked myself, what would you do if you were, say, Evelyn Gallagher—NSA analyst, single mother to a small deaf son, mostly intent on keeping your head down—and you discovered the existence of a program as vast as God’s Eye? And what if you were a contractor assigned to assess and eliminate Gallagher—say, Marvin Manus, a badly damaged giant of a man intent on protecting the director of the NSA and struggling with a growing attraction to the woman you’ve been tasked with killing? How much would you double down if you were, say, Theodore Anders, the director of the NSA itself, and you believed an employee had become an insider threat to the most far-reaching spy program in history? And how far would a mother like Evelyn go to protect her small son with the full might of the national security state arrayed against her?

I know not all novelists are comfortable with the notion of depicting our ostensible protectors as villains. But I think that reluctance misses an important dynamic. To analogize for a moment: The body will generate a fever to destroy a pathogen. But a fever that runs too hot and too long can become more dangerous to the body than the original pathogen ever was. This is the world I believe we inhabit post 9/11—a world in which we have less to fear from non-state actors than we do from our own overreactions. After all, America is the most powerful nation the world has ever seen. It’s therefore unavoidably true that we can do far more damage to ourselves than any enemy ever could—if we lose our heads, and our values, and turn all that power on ourselves. So even beyond the inherent attraction of realism, if maximum danger means maximum thrills, in a political thriller it makes sense to depict the gravest dangers a society can face.

And while the fever analogy applies generally, the NSA is a particularly acute example, both because its original mandate was exclusively overseas, and because the changing nature of technology has enabled the organization to spy on virtually every aspect of human behavior. As I wrote in 2013 on the topic of post-9/11 governmental overreach:

The National Surveillance State doesn’t want anyone to be able to communicate without the authorities being able to monitor that communication. Think that’s too strong a statement? If so, you’re not paying attention. There’s a reason the government names its programs Total Information Awareness and Boundless Informant and acknowledges it wants to “collect it all” and build its own “haystack” and has redefined the word “relevant” to mean “everything.” The desire to spy on everything totally and boundlessly isn’t even new; what’s changed is just that it’s become more feasible of late. You can argue that the NSA’s nomenclature isn’t (at least not yet) properly descriptive; you can’t argue that it isn’t at least aspirational.

As with all my novels, ultimately what I set out to do with “The God’s Eye View” was to drop fictional characters into real situations, both as entertainment and also because “Nonfiction is fact; fiction is truth.” In this regard, early reader reactions have been encouraging: a lot of, “Loved the book, and then I came to the bibliography and thought, ‘Holy smokes, this stuff is all real?’”

Yes, it is. And when a program like God’s Eye is revealed in tomorrow’s news articles and history books, remember: “Fiction” got there first.