Much of the down-home soul I remember hearing from my childhood explored the joys and pains of outside love. It was a popular lyrical theme in R&B in the early seventies, the newlywed period for my parents. I didn’t come along until 1977, when disco thumped everywhere but not in the Ollison household. Blues-suffused soul and traditional gospel sparked good vibes and sustained us through bad times.

The come-hither croon of Eddie Kendricks and the symphonic love letters of Barry White were the soundtrack to the early years of my parents’ marriage.

But by the time I was in kindergarten, their union had cracked and the songs darkened. Just about all of the records Daddy dug had something to do with cheating. And he certainly wasn’t the only one listening. Just about everybody I knew had half brothers and sisters, “outside babies,” as folks called them.

Clara Mae wasn’t Daddy’s only sidepiece, but she was the only one whose house I knew and whose food I ate. During my parents’ marriage, two women bore children with strong Ollison features: thick eyebrows with high arches, full lips, and bulbous noses.

Mama, who was a few months pregnant with me, read the baby announcement for the fi rst one in the morning paper. The baby’s name, Antonio Ramon Ollison, stopped her because she had initially picked it for me. Apparently, Daddy liked the name enough to suggest it to the baby’s mother, a young Malvern woman barely out of high school.

Mama forgave him after Daddy promised he’d never do it again. But he lied just as Johnnie Taylor did in “Running Out of Lies.” It was “getting hard to think of an alibi.”

Barely two years after my youngest sister, Reagan, was born, another woman in Malvern had another son. Mama had had enough.

Before he moved out of our house on Garden Street, Daddy spent hours playing those baby-I-didn’t-mean-it songs in the living room in the dark: a cold Miller in one hand and a Viceroy burning in the other. He’d chuckle at a verse. But mostly, he stared straight ahead as an anguished voice on the stereo crooned how trying to love two sure ain’t easy to do.

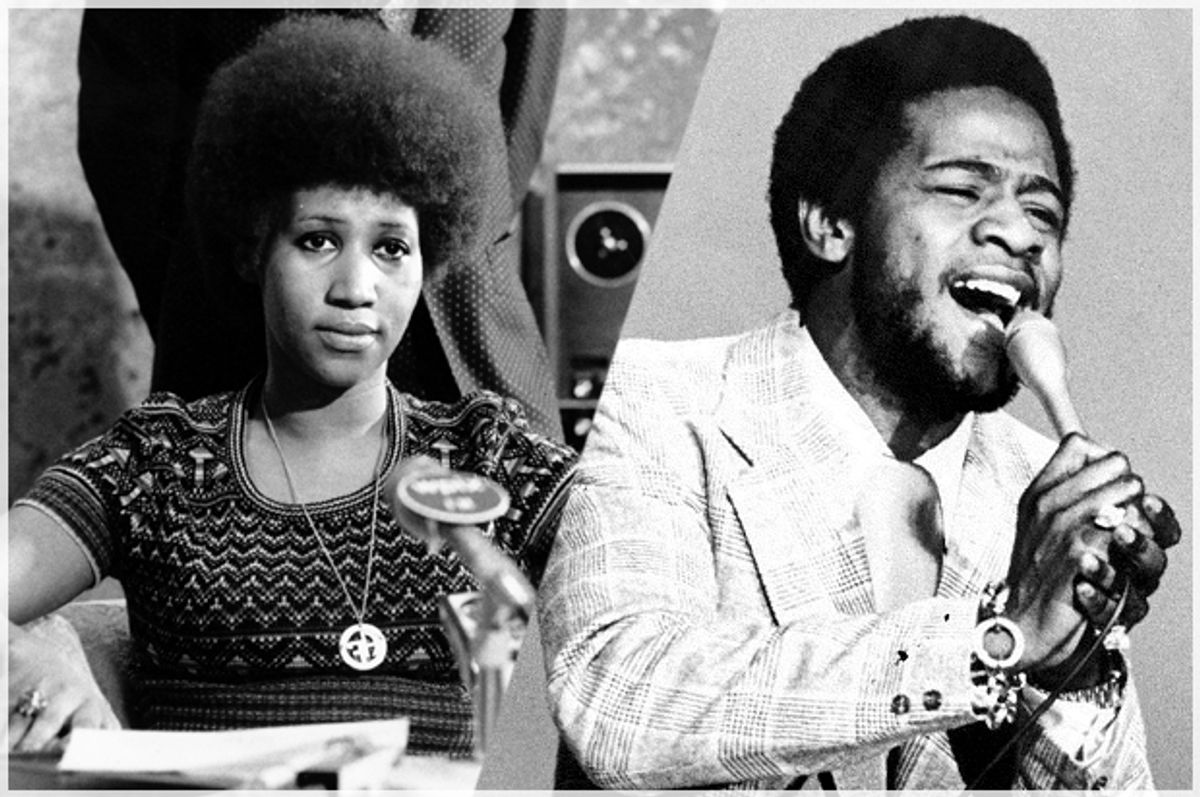

As the shattered pieces of the marriage settled around her, Mama knelt at the altar of Aretha.

She played Amazing Grace, the legend’s landmark 1972 gospel double LP, seemingly every waking hour during the turbulent years of the marriage, the only years I remember. The album often played on Sunday mornings as we got ready for church.

The fiery, holy sounds of Aretha shouting the good news, shadowed by the Southern California Community Choir, sometimes filled the house well into the night.

Daddy wasn’t home much during the last two years of the marriage. Some of his things (his shoes, his clothes, many of his albums) disappeared. I didn’t know where he stayed. Clara Mae’s? Big Mama’s? Whenever he showed up, he and Mama fought. Daddy, as usual, was drunk and the first to lay hands, shoving Mama against a wall, on the couch, on the floor. But she always fought back: kicking, scratching, and biting.

She clocked him in the head once with a phone. Her nostrils flaring, Mama set it down, carefully placing the receiver back on the base. Then she looked at us as we stood there scared and shocked.

“Y’all get somewhere and sit down,” she said, stepping over Daddy, as he moaned and writhed on the floor, holding his head.

But whenever Aretha was on, order seemed restored. Her majestic voice grounded us, especially Mama. After she came home from her job at Coy’s restaurant, where she prepared fancy salads all day, Mama often reached for Aretha.

The songs she played indicated her mood. If “Respect” or “(Sweet, Sweet Baby) Since You’ve Been Gone” rocked the house, her spirits were up; soaring ballads such as “Angel” and “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” meant she was reflective; moody cuts like “Ain’t No Way” and “Do Right Woman, DoRight Man” meant she didn’t want to be bothered. So we tiptoed around her.

Even as a child I gathered that Aretha’s music, especially her classic Atlantic recordings, was an extension of church. The air changed. A sense of reverence rained down as her voice soared from the speakers. I straightened up and listened. Coupling the skyripping strength of Aretha’s voice with Mama’s warrior-woman presence, I felt protected in Daddy’s absence.

So much of Mama’s life was reflected and refracted in Aretha’s lyrics: the longing, the loss, the hope, the faith, the perseverance. In 1967, the year of the singer’s pop breakthrough, Mama turned seventeen. She entered womanhood with the Queen of Soul as a cultural guidepost.

Aretha was the natural woman/genius from down the block, world-weary and accessible, nappy edges and all on full display. She mingled the muddy funk of the Delta with the cosmopolitan sleekness of the North. And in her music, Mama seemed to always find a home. She admired other dynamic black female singers of her generation and played their music often. Diana Ross and Gladys Knight come to mind. But her reaction to their songs wasn’t the same as when Aretha sang. Mama swayed and rocked. She waved her hand in the air, the way she did in church. Sometimes she cried. In 1983, her marriage fell in sharp glittering pieces all around her. My oldest sister, Dusa, was fourteen; Reagan, the youngest, was five; and I was six. Garden Street was bleak, save for the aural sunbeam of Aretha singing through the surface noise of well-worn vinyl, assuring us that God would take care of everything.

In the summer of ’83, a few months before my parents’ divorce was final, we moved into the housing projects over on Omega Street.

The apartment felt like a step up from our place on Garden. That house, a small white one with three bedrooms, had been built sometime in the 1920s, with a wide front porch and not much of a yard in the front or the back. It faced the old National Baptist Hotel, at that time an abandoned building my sisters and I thought was haunted. Decades before, the majestic red-brick hotel attracted every major black performer who came to Hot Springs. The building, which took up a block, included a bathhouse, a performance venue, a conference center, a gym, and a beauty parlor.

The neighborhood surrounding the National Baptist Hotel had been a glorious one in the years before integration. Black doctors, lawyers, teachers, and other professionals lived in the stately homes, some of which were teetering on dilapidation just before we moved out. Reagan and I rode our Big Wheels up and down the hill in front of our house. Drunks staggering out of the dives and liquor stores on Malvern Avenue, the main drag that ran perpendicular to Garden Street, were mostly nice. Some were even parental, telling us to be careful on our Big Wheels and to stay out of the street.

We were all happy to leave that old white house, which was also home to mice and roaches. I remember once going into the kitchen and seeing a mouse swimming around in the cold, greasy dishwater left overnight in the sink. I almost pissed myself.

Daddy’s absence hung over everything. I missed our clandestine trips to Clara Mae’s; to the liquor store on the street directly behind the house, where he bought me Guy’s potato chips and Dr. Pepper; to the homes of his drinking buddies, where I was treated like one of the fellas. I wasn’t given beer to drink, though occasionally Daddy gave me a quick sip of his and laughed his wheezing laugh as I frowned and gagged at the acrid taste.

I sat among his ragtag friends and absorbed their tall tales peppered with “bitch” this and “muthafucka” that. For the longest time, I thought my name was “Lil’ Mafucka.” As I followed Daddy into smoky backrooms, a grinning drunk man with a beer in his hand knelt down to rub my head and say, “Hey there, lil’ mafucka.”

I remember the last time Daddy darkened our front door on Garden Street.

It was a Saturday morning, and Mama was at work. Dusa was in charge, sitting on the couch talking on the phone, as usual. Reagan and I were glued to the TV, eating cereal and watching The Smurfs, when the door opened and in walked Daddy.

We rushed him, hugging his legs. I couldn’t remember the last time he had been home.

He hugged us and went into the bedroom he shared with Mama. We followed him, pelting him with questions: “You come home, Daddy? You stayin’, Daddy?”

“Y’all go on back in the living room now,” he said. “Go on.”

We went back into the living room, giddy that he was home at last. After he was in the room for a while, I snuck in. He sat on the edge of the bed crying, something Daddy often did when he was drunk. So this wasn’t an unusual sight.

He looked up, saw me, and sobbed.

“Your mama don’t love me no more,” he said.

I saw the luggage at the foot of the bed.

“I wanna go,” I whined.

“Nah, you can’t,” he said, lifting himself off the bed.

He picked up his suitcases and headed out of the room. As he walked through the living room, Reagan jumped from her spot in front of the TV.

“Daddy, where you goin’?” She was in tears.

“I’ll be back,” he said, hugging us both. He looked over at Dusa, who was still on the phone. Daddy had been a father to her longer than he had been to us, and yet she seemed indifferent to his departure.

“Tell your mama I’ll call later,” Daddy said to Dusa, who just nodded and said, “Okay.”’

“Y’all be good,” Daddy said as he closed the door.

We didn’t realize that Uncle Alvin, the husband of Daddy’s sister Stella, had been outside the entire time waiting in the car. From the living room window, I saw Daddy load his things and get in. He and Alvin sat there for what seemed like a long time before leaving.

Daddy haunted every room on Garden Street. He lived barely an hour away in Malvern. But he may as well have been across two oceans because he didn’t come around. In the new room I shared with Reagan on Omega Street, I kept a stack of 45s he’d bought me—music that connected us.

The projects were designed like townhomes. Our three bedrooms and bathroom were upstairs. A kitchen with washer and dryer hookups was to the left as you entered the front door. Each unit had a small front porch; some had a small back porch, too. The grounds were well kept.

Barely a block away, there was a park with a tennis court, a basketball court, swing sets, a merry-go-round, and a large pavilion, where DJs in the summer spun the latest in R&B and hip-hop.

The music in the air during the summer or whenever the weather was warm and mild enlivened Omega Street. Neighbors dragged their stereo speakers out on porches or perched them in windows, and the gritty sounds of Z. Z. Hill, Lakeside, or the latest punk funk by Rick James complemented the sun-kissed weather and the aroma of ribs sizzling on a grill.

You identified the neighbors by the music they played. Next to us, Betty played the blues first thing Saturday morning—the slick Southern kind, Denise LaSalle, Latimore, and Johnnie Taylor. Sherry, who sometimes lived with her grandmother Miss Wyrick across from us, played Luther Vandross all day. And from Sharon’s unit three doors down, the effervescent funk of Shalamar and the sleek romantic duets of Alexander O’Neal and Cherrelle blared routinely.

No men were around, save for somebody’s no ’count boyfriend or a creeping married man breezing in and out. The block was dominated by single women, all black, raising their kids and everybody else’s. Some were elderly and retired, like Miss Wyrick. A matronly, gossipy woman, she and Mama became fast friends.

Loud Miss Wells, who policed the grounds (“Child, you betta pick that candy wrapper up!”), lived two doors down. Betty next door to us was one of Miss Wells’s daughters and a projects diva. Svelte and stylish with no job, Betty smoked cigarettes and in the summer squeezed her cantaloupe breasts into tube tops. She threw loud card parties that went on well past midnight, which pissed off Mama, the only woman on the block who got up every morning and went to work. Everybody else waited for the welfare checks to come the first and the middle of every month, which is usually when their boyfriends showed up.

Betty’s sister Dot lived a few doors down across from her. She was also a tube top–wearing projects diva, who strutted around like a peacock with nails painted shades of purple, yellow, or blue. Her voice was loud, like her mama’s. When she wasn’t strutting from door to door, she was cussin’ and fussin’ at her badass boys, T.J. and Prince, who were about the same age as Reagan and I.

My sisters immediately took to our new neighborhood, spending hours on the porch and chatting with folks. I was glad to be in a place free of mice and roaches and the sight of the creepy Baptist Hotel. But I withdrew.

It seemed I mourned the breakup of my parents’ marriage more than anybody else in the house. Daddy could be stormy when he was home, usually as gin streamed through his system. But there were calmer times I relished.

We used to eat sardines with yellow mustard and saltine crackers at the kitchen table, just us two, because nobody else in the house liked them. When he wasn’t working the graveyard shift at Reynolds, Daddy was up during the early part of the afternoon. In the summer, he took us to the park or out for a ride. He watched old westerns and cartoons with us on the couch.

Sometimes on Fridays after he picked me up from my kindergarten class at Langston Elementary, we stopped by the Dairy Queen for a cherry slush, then went on to the dusty record shop downtown that sold new and used music. Daddy bought himself albums and picked 45s he thought I needed to hear.

“This here is music you should know ’bout,” he said.

I showed off my records to Mama when we got home.

She shook her head. “Why you buy this boy all these old-ass records? What the hell he know about Johnnie Taylor?”

Daddy laughed as I spun the blues on my Mickey Mouse record player.

But over on Omega Street, I felt as though I were standing in a river. Everything just kept moving as though Daddy never existed. Mama had a new job at a hospital, and her hours were long. Dusa, who turned fifteen just before we moved, had a part-time job after school at Taco Bell. Well developed and pretty, with Mama’s creamy skin, keen features, and lush dark hair, she kept herself busy with the boys in the neighborhood when she wasn’t in school or behind the counter for a few hours at Taco Bell.

Some of those boys regularly snuck in the house through the back door when Mama was at work. They couldn’t come through the front, not with Miss Wyrick perched at her kitchen or bedroom window, both of which faced the front of our unit. She’d surely let Mama know that So-and-So’s mannish boy was over there.

We never told Mama about Dusa keeping company. Reagan did anything she said, so she wasn’t going to tell. I kept quiet, because Dusa was bigger and threatened me with force: a punch in the shoulder, a kick in the leg, a slap upside the head.

An only child for nearly nine years, Dusa never got over the fact that I was born. She was the creamy-skinned dream child relatives adored, with long hair, a living doll with Shirley Temple vibrancy. The girl danced and sang for anybody who paid attention, and Dusa loved attention. Mama Teacake’s attachment to her bordered on possessive.

According to family legend, Dusa strongly resembled Jannette. My grandmother had her favorites and made no qualms about it. In her eyes, I guess, Dusa was her second chance with Jannette. Mama Teacake rarely smiled, but her face brightened whenever Dusa appeared. When the bubbly girl left her sight, Mama Teacake’s face fell back to its usual fuck-you expression.

Dusa had no relationship with her biological father, who moved to California soon after she was born. She was barely two when Daddy and Mama married, and he spoiled her as though she were his own. That changed when I was born. Then Reagan came a year and five days later. Dusa had to share attention in the house, and this fucked with her for years.

By the time we were on Omega Street, Dusa had been saddled with more responsibilities than her age and emotionally fragile nature could handle. But she played the part of the steely woman-child, fumbling new liberties and exploring her sexuality with boys from around the way.

I didn’t care about what she did on the couch or in her bedroom with those knuckleheads. But I don’t think anybody had to tell Mama a thing. That year, she put Dusa on birth control.

With Mama working all the time and Dusa busy with school, Taco Bell, and fucking, Reagan and I were forced to be independent. At six and seven years old, we let ourselves in the house after school and fixed sandwiches or bowls of cereal if Mama hadn’t left something cooked in the oven. Dusa usually got home a few hours later and ran everything. If Mama hadn’t cooked, Dusa handled the pots and pans. Her fried chicken was red at the bone, and the frozen Banquet potpies were still cold in the middle when she took them out of the oven. Dusa checked our homework and put us to bed. Sometimes the entire day passed without us ever seeing Mama.

I escaped into my records.

The swirling shades of purple mesmerized me. The hallelujah voice trapped inside the wax sang about losing her mind over something she heard through the grapevine.

Reagan played outside with the neighborhood kids, but I preferred to sit in our room next to my record player. The rest of the world disappeared while I stared at the 45s spinning. The colors of the labels attracted me first. Purple and yellow were favorites. When Daddy and I were in the record shop, I picked 45s with those colors.

"Daddy, this one.”

He plucked it from the row and read it. “Oh, yeah. You gonna like this.”

“It’s yellow,” I said, grinning.

Daddy bent down to show me the label. “Can you read this? That’s the Staple Singers.”

I pointed to another row. “That’s a purple one.”

“Hold on. Let me see,” Daddy said, plucking the record. “Oh, yeah. Gladys Knight & the Pips.”

As the music played, I thought about Daddy and ached for him. Whenever I asked Mama about his whereabouts, her face tightened: “Boy, go somewhere. You ain’t got no daddy.”

I felt a sting inside each time she said that, which was often.

I changed records. The label was lemon-yellow with a black rectangular box on the left. Inside, slender brown fingers froze in a snap. The voice, as earthy as turnip greens, sang of a place where “ain’t nobody cryin’” and “ain’t nobody worried.”

She sure wasn’t singing about No. 1 Omega Street.

Excerpted from "Soul Serenade: Rhythm, Blues, & Coming of Age Through Vinyl" by Rashod Ollison (Beacon Press, 2016). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press. All rights reserved.

Shares