Across Iowa, people have been gathering in churches, living rooms, their local Pizza Ranch. They come to voice their fears and hopes to neighbors and strangers and members of the press. For Iowa, the caucus is more than a night, it is a season when the corn-fed heartland is the hot-blooded heart of American politics. And for months Iowans have been our pulse. “I love all of it,” said James Payton at a recent rally for Donald Trump. “I love going to the events, I love the ads, I love the whole experience and everything about it. I’m disappointed it’s ending, everyone’s going to leave, and then it’s going to be over. We’re another fly-over state that nobody cares about.”

Last week, I attended a caucus training for Trump supporters in the town of Toledo, Iowa. When pundits talk about the importance of a ground game, they mean events like this that draw people out of their homes and make them committed caucus-goers — and a major question has been whether Trump’s ground game is any good.

“I idolize this man,” said the facilitator, Frank Moran, about Trump. Moran owns a GNC at the local mall and claims to have spent 80 percent of his savings volunteering for Trump. Thirty of us sat in the community room of the State Bank of Toledo under fluorescent lights, noshing on homemade bars and drinking coffee. Moran asked each of us to offer a testimonial explaining why we support Trump.

“I’m so tired of people calling us a bigot,” said a man who didn’t give his name. He came with his Filipino wife, who he’d met on the Internet. As if to explain why he’s not a bigot, he told a story.

“It started out just by accident,” he said. “Two years ago I didn’t know what a Muslim was. I would see one and I would smile and say ‘hi.’ It was like I was a ghost, they couldn’t see me. It turned into a little project. Every time I got done with work I’d go down to the strip mall, seek out Muslims, say ‘hi’ and smile. I did this to over a hundred Muslims, nobody would even smile.” He returned, then, to Trump. “When he says that this” —Muslim immigration to the US — “could be a Trojan horse, he’s holding back. He knows damn well it’s a Trojan horse. They’ve got these seed cells all over America, and they are not coming here to abide by us.”

People in the room agreed. They nodded their heads, uttered exclamations. The potent sense in the room was that we in white America are in imminent danger— and not only from the Muslims. A middle-aged man named Tom explained. “Before we moved here we lived near a town of 7,200 people, predominantly white. O.K.. Meat-packing house is there — large — they employ 3,200 people. The town now is over 80% Hispanic. Most of the whites have moved out, the town looks like a ghetto.”

Tom’s anecdote and the earlier man’s story of his Muslim “project” are examples of the archetypal Trumpian narrative: things used to be good (i.e. white); now they are bad (i.e. non-white, ghetto). It has proved a narrative fit for the zeitgeist. The trick for Trump will be to get its partisans out to the caucus Monday night. That was Moran’s task.

“We’ve been here 40 minutes,” he said. “Basically, on caucus night, you’re going out the door. This is pretty painless. Other than writing Trump’s name on a piece of a paper, this is basically what it is.”

If the candidates have come to Iowa steadily since August, this past week they and their surrogates and their volunteers and their ads have bum rushed the state. The hotels are all booked. Small talk permits no other topic. On Thursday morning, at the Gateway Market in Des Moines, I asked Carol Simms-Davis whether she was following the caucuses.

“Yeah,” she said, laughing. “I’m an Iowan.”

Simms-Davis, a mental health therapist, was drinking coffee and poring over her heavily annotated King James Bible. She is an evangelical Christian and studies the Bible for personal edification as well as to teach groups of men. This morning she was reading the Book of Proverbs on wisdom.

“‘Be not wise in thine own eyes,’” she said, quoting Proverbs. “Donald Trump,” she continued. “He’s out for me.”

She considers herself a Republican and believes in the party’s platform, “but not so much the candidates.”

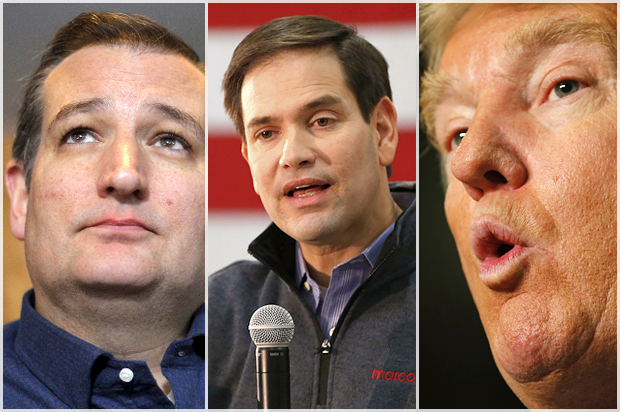

Trump? “Scary, a Johnny-one-note, an egotist, and not presidential.” Ted Cruz? “I didn’t like when he shut down the government. He’s volatile.” Marco Rubio? “Still wet behind the ears.” Ben Carson? “I need to figure out who he is as far as Christianity is concerned. He says he is a Seventh-day Adventist, they have some different doctrines. I wouldn’t vote him, even though he is black and I’m black. Doesn’t mean a thing.”

All in all, she said, the Republican candidates “suck.” She laughed. “Excuse my French.” She plans to vote for Hillary Clinton.

John Zeller — another Gateway Market regular — sat at the next table, studying Italian. “Oh yes,” he said, “I love to caucus. It’s fun. At least the Democratic ones.” At the Democratic caucus, voters gather according to who they support, but if their candidate fails to reach 15% of attendees, they have to disband and support another candidate. This is when the Iowa caucus gets wild, because supporters, say, of Sanders and Clinton will attempt to convince Martin O’Malley supporters, in real time, to come to their side. For Zeller, the fun is in forcing others to convince him.

In 2008, Zeller and his twin brother began with Bill Richardson, knowing he would be unviable, so that others would have to convince them. They believed that the media, particularly, Zeller said, “Japanese TV,” would find the spectacle of the obstinate twins compelling. “You could just tell that the crowd hated us,” he said. “We were just, you know, basking in our glory. Just making them sit there for another half an hour.” Without apparent irony, he concluded, “It’s a long evening.”

Where will he end up tonight? He said that, despite his attraction to Bernie Sanders, he’s eager to see “that the Democrats win and we don’t have the Republicans put three troglodyte Supreme Court justices in. So I’ll hold my nose and vote for Hillary.”

Neither Simms-Davis nor Zeller were at the Gateway Market that morning for the main event: breakfast with Rick Santorum — a man as well known for being a former Pennsylvania senator as for lending his name to a byproduct of anal sex — who many, even in Iowa, had forgotten was running. The event drew 25 people, 10 of whom were journalists, which meant every attendee was interviewed multiple times. (During caucus season, people in Iowa are so accustomed to speaking to journalists at political events they often begin unprompted by spelling their surnames for the voice recorder.)

William and Rose Yost are devoted Santorum supporters. Several months ago they hosted him for an event in their home. “What was supposed to be 45 minutes,” said Mr. Yost, “turned into three hours.” Mrs. Yost fed everyone “two and then three times.” At the end of the night, they loaded up Santorum’s crew with “stacks of Italian cookies.”

“That’s Rose,” said Mr. Yost. “She has to feed everyone.” That morning Santorum fed us. We listened to him defend his candidacy over plates of cinnamon rolls and Denver scramble.

The night before, anyone who was interested had the chance to see Rubio, Carly Fiorina, and Cruz speak back-to-back-to-back at three events within six miles of one another in the suburbs west of Des Moines. Rubio presented his stump speech at Wellman’s Pub to a well-heeled crowd of business professionals as they sipped glasses of wine or local microbrews. According to The New York Times, middle-class, college-educated suburbanites ages 30 to 45 are the Rubio campaign’s target demographic, and they were in ample evidence at Wellman’s.

Fiorina spoke in the back room of Rube’s Steakhouse. At Rube’s, a diner has the option of selecting her own raw steak and cooking it herself. Fiorina made her pitch, but with technical difficulties — a detail that resonates with the struggles of her campaign. As I left, her microphone quit working and she was speaking loudly to the elderly attendees, asking if they could hear her.

Down the road, Cruz drew an impressive, standing-room-only crowd for an endorsement-studded pro-life rally. To find parking, SUVs hopped curbs and sedans squatted at the edges of intersections. Inside, supporters in red, white, and blue Cruz sports jerseys jockeyed their way into a position to see him. But first, we listened to remarks from Congressmen Steve King and Louis Gohmert, Gov. Rick Perry, and evangelical leaders Bob Vander Plaats and Tony Perkins. When Cruz rose to speak, the crowd erupted with religious fervor.

“One hundred and nineteen hours,” said Cruz, counting down until the caucus. He structured his speech around what he called “seven times for choosing,” selecting a number with Biblical echoes of the apocalypse. Whether it was immigration, gun rights, or the Affordable Care Act, Cruz was alone, in his narrative, on the right side of history. He closed by asking us all to pray between now and November “for Christ to pull us back from the abyss”— the abyss, apparently, of his potential electoral loss.

It is Trump, though, who draws the biggest crowds — and who raises the biggest question. Half the people I spoke with at a recent Trump rally in Iowa City came for the spectacle, or to protest. Early in Trump’s speech, a young man threw two tomatoes at the stage, missing Trump wide left. After that, protesters repeatedly interrupted Trump by blowing shrill whistles, forcing him to cut his remarks short.

Annie Ventullo, a family and child therapist, organized the protest. “If this fascism continues in this country,” she said, “I don’t want to say I didn’t do everything I could to stop. So I’m spreading peace and love.”

But I spoke to many others who support Trump, and — while all white — they surprised me with the diversity of their professions: kindergarten teacher, aspiring animator, computer systems analyst, hospital freight clerk, the owner of Iowa City’s Café Vape, purveyor of electronic cigarettes. Will these people, many of whom have never caucused before, caucus tonight? Are there more Trump supporters than we think, or fewer? These are the questions that pollsters, pundits, and the rest of us are waiting now to find out. The race couldn’t be closer. At the time of writing, Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight has Trump’s odds at 47%, Cruz’s at 40%.

The owner of Café Vape told me that he knows “a lot of people that wouldn’t come to this” — the Iowa City rally — “because they don’t want to be depicted as Trump supporters. Because it’s depicted as negative.” Will these ashamed Trumpeteers cast their votes?

James Payton, the man who loves everything about the Iowa caucus, represents a final, and crucial, demographic: “I consider myself a Trump Democrat as there were Reagan democrats,” he said. “And I think there’s more people out there like me than people realize.” He suspects Trump will win handily.

It’s time to find out if he’s right.

Dan Sinykin is an assistant professor of English at Grinnell College.