The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world. A 2013 study reports that while the U.S. accounts for only 4.4 percent of the world’s population, it has 22 percent of the world’s criminals. Yet, despite all of this jail time, Americans are crying out for justice. The recent Netflix documentary “Making a Murderer” decries the inept working of justice in Wisconsin that led to the faulty conviction and incarceration of Steven Avery for rape, and later muddied the certainty of his later conviction for murdering Teresa Halbach. Later this year, Graywolf Press will rerelease “The Red Parts,” Maggie Nelson’s memoir of the trial for her aunt’s 1969 murder, which, in part, focuses on the inability of American justice to truly provide closure or retribution.

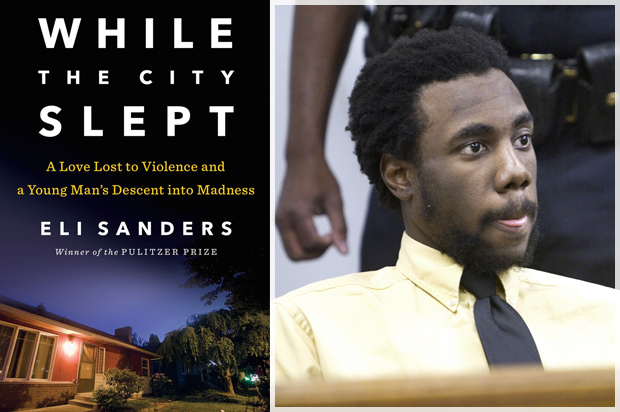

Joining this chorus is Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Eli Sanders, whose new book “While the City Slept: A Love Lost to Violence and a Young Man’s Descent Into Madness” (out Feb. 2) looks at the deplorable state of mental health care in America through the story of Isaiah Kalebu and his victims, Jennifer Hopper and Teresa Butz. The book follows the intersecting lives of the three individuals and concludes with the trial and conviction of Isaiah Kalebu for the 2009 murder and rape of Teresa Butz and the rape of her partner Jennifer Hopper. The book takes a hard and long look not just at the violence itself, but at Kalebu’s years of personal, emotional, institutional and even governmental neglect.

The book begins with a map of Kalebu’s neighborhood, South Park, Seattle, and a detailed description of its decline. From the beginning, Sanders builds the connection between the crumbling infrastructure of the town and the crumbling lives of its residents. The pattern is clear—when people and places are neglected, things fall apart. Studies back up Sanders’ metaphor. Even prior to incarceration, people in jail had a median income of 41 percent less than non-incarcerated people of similar ages, are more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods and lack access to education and basic mental health services.

And like the rotting bridge that connected his neighborhood to the city, Kalebu spent the majority of his life needing help that never came. Sanders makes this point clear in his book, describing the many times Kalebu was recognized as being in dire need of intervention. The first moment of note happened in school when a teacher noticed that Kalebu struggled in class, despite his intelligence. His parents, entangled in an emotionally and physically abusive marriage, dismissed the teacher’s suggestions out of hand. Later, during his parent’s contentious divorce, Kalebu was flagged as needing counseling. As Kalebu continued to lag behind academically, still in need of mental health help, his father enrolled him in Seventh Day Adventist schools—a denomination that strongly counsels against medical intervention in the lives of its followers. While Seventh Day Adventists are only a small portion of the denominational mix in America, the denomination’s bootstrap approach to mental health reverberates in a nation where a lack of understanding feeds into prejudice. Sanders describes how Kalebu’s immigrant father often took a “work harder” approach to problems in life. And Kalebu himself held fast to this belief, insisting, even after his mother and sister pleaded for him to get help in the days leading up to the murder, that he was still master of his mind.

This attitude persisted during the trial as Kalebu sought to use his mental health as a means of defense — at one point, he testified that God told him to attack “his enemies,” whom he identified as the victims — without ever admitting to needing help. After all, needing help is one of the worst things you can admit to in a country where the national myth is that a “can do” spirit and “work hard” ethic can triumph over anything.

But that national myth is crumbling, as story after story reveals that cycles of poverty and injustice are impossible to end. Like Kalebu, Stephen Avery grew up in a place beset by poverty and neglect. And whatever the status of Avery’s guilt or innocence, in order for justice to prevail, the system has to work at every level. And it did not—not for Avery and not for Kalebu, because like the places they are from, they were ignored and dismissed until the very moment when they become a danger to themselves and others. Sanders makes the case that if Washington state had put the proper resources and funding into its mental health clinics, the rape and murder of Teresa Butz and the rape of Jennifer Hopper would never have happened. And yet, it’s possible to go back farther, to Kalebu’s teachers who very early on noticed a small boy in need of help — teachers who also lacked the resources themselves to help a small child in need.

Sanders humanizes not only Kalebu’s victims and family, but Kalebu himself, allowing the reader to see him as he is—a human, full of potential for both good and for ill, a man who, because of neglect, fell apart and now sits in prison, and is again neglected. That’s what we call American justice.

In “The Red Parts,” Maggie Nelson clearly articulates the emptiness of justice. She writes, “[Justice] always swoops down from on high—from God, from the state—like a bolt of lightning, a flaming sword come to separate the righteous from the wicked in Earth’s final hour. It is not, apparently, something we can give to one another, something we can make happen, something we can create together down here in the muck. The problem may also lie in the word itself, as for millennia ‘justice’ has meant both ‘retribution’ and ‘equality,’ as if a gaping chasm did not separate the two.”

In America, our answer to crime only focuses on the end game—that grand sweeping gesture of a trial, jail time, or the death penalty, as if the whole process offered any sort of remedy for the deep wounds of our society. Crime creates a need for both retribution and equality, but both of those cannot occur at once if we only focus on the aftermath of a crime. Sanders calculates the total cost so far of incarcerating Kalebu as well over $3 million — money he says that could have been used more effectively to provide counseling and psychiatric intervention. With an estimated 20 percent of the prison population struggling with mental illness, Sanders argues for a more comprehensive approach to justice, one that begins at the very start of a person’s life—one that seeks to rebalance the injustice we hand to our children just by virtue of their being born. If justice is to work, it has to work to right every wrong and work on every level, for every one, even before we are left bleeding in the streets.