Americans are increasingly supportive of hiking the minimum wage to a degree that would have been politically unthinkable as recently as 10 years ago, so the usual arguments against it don’t pack quite the punch that they once did.

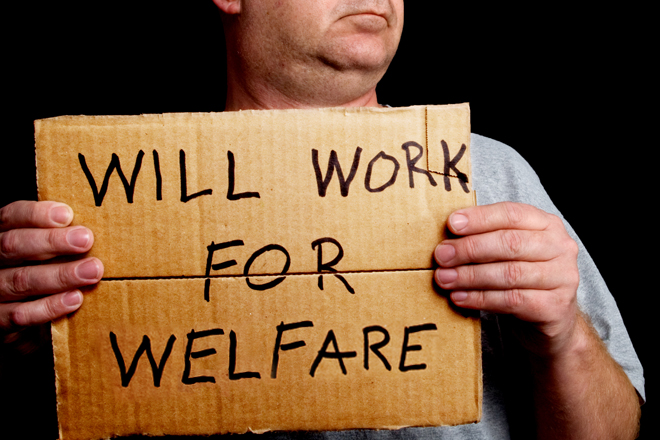

Still, if you peruse Twitter or Facebook on a day when fast food workers are protesting, you’re liable to find, mixed in with all the usual poor-bashing, a whole lot of specious arguments about how a higher minimum wage would end up hurting consumers — and, ultimately, the government’s bottom line. Don’t believe them.

On the question of whether paying workers at your favorite fast food joint a living wage will render the chunks of corn syrup and sodium they sell unaffordable, the answer is no. There probably won’t be any affect on price whatsoever, of course. But we’re talking cents here; often less than a quarter’s difference. It is extremely likely, in other words, that you can afford it.

It turns out, however, that the other line of argument — that raising wages would hurt the economy and end up leaving taxpayers with the bill for cleaning up the mess — isn’t true, either. And as anyone who’s ever read a story about Wal-Mart (or McDonald’s) and Medicaid knows, it’s not like the government isn’t paying for bad wages already.

Now there is a report, released by the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute earlier this month, that adds further credence to this line of analysis. Titled “Balancing paychecks and public assistance: How higher wages would strengthen what government can do,” EPI’s new report shows that policy designed to give American workers a raise wouldn’t just be the right thing to do in terms of economic and social justice. It’d help create a more efficient and effective government, too.

Recently, Salon spoke over the phone with David Cooper, the study’s author, about his findings as well as their larger implications. An edited version of our conversation can be found below.

So what was the overarching public policy question you wanted to address with this study?

The motivation behind the study is the recognition that it takes a lot of income for folks to have a decent quality of life. We have a tool called the Family Budget Calculator that calculates throughout the country what we would consider a modest, but adequate, standard of living. It tells you exactly what we expect one would need to cover everything from housing, rent, a car payment, childcare, healthcare, and when you add up all those numbers, it comes up with a budget. In most parts of the country, those numbers are a lot higher than you would get if you were, say, earning the minimum wage in most places.

Right. Even if they show up and work hard every day, for many people on minimum wage, it’s not enough.

As a consequence of that, I think most people looking at public policy would say that it’s reasonable to expect that for some portion of the population, you’re going to need to have income coming from labor, as well as some sort of supplement from the government.

We have public assistance programs to provide a safety net when folks lose their job or suffer some shock to their income and they need that extra support. We also, in a lot of cases, have people that have special circumstances that need support from the government, be it they are disabled or have a sick child or something like that that requires them to have some support from the government.

So in other words, I think it’s reasonable to expect that for a lot of people, it’s going to take a combination of both income from a job and income or in kind support from public assistance programs.

So in the absence of that, what questions arise?

Have we set up a scenario where businesses are effectively shifting some of their costs onto taxpayers, because taxpayers are footing more and more of the bill when it comes to providing the benefits and income that people need to get by?

And what did you look at to try to answer that question?

What is the composition of folks who are receiving public assistance who also work? What are the levels of benefits they are receiving? What are the hourly wages that they’re making?

Our belief was that, in all likelihood, there are certain industries and certain places where folks are being paid so little on the job that it’s essentially forcing people to turn to these public assistance benefits because they just don’t have any other option.

What do you mean by “public assistance”?

When I say public assistance I mean the programs that are dependent purely on your income level. So I’m not talking about Social Security or Medicare, which specifically targets the elderly population, or disability, which specifically goes to folks who have a disability or a disabled family member. I’m talking about the programs that are universally available for folks with low income. Things like food stamps, SNAP, EITC, the child tax credit, energy assistance, housing assistance and the WIC program for women with young children.

Got it. So when you look at all that spending, what do you find?

We find that about 70 percent of all of those benefits being paid out through those programs among non-elderly families are going to working families. We also find that among those folks that are receiving benefits and working, about half are working full-time. So it isn’t even the case that these are folks who are working part-time and looking to their benefits to pay the bulk of their bills. A lot of them are working full-time and still can’t make ends meet on what they’re getting from the job.

These aren’t a bunch of 15-year-olds working in these jobs, either.

We’ve done a lot of work on who would be affected by raising the minimum wage. That obviously is the most directly relevant policy to this paper. In the paper we talk about how raising wages generally would affect utilization of public assistance, but clearly the policy that’s going to raise wages right away is going to be raising the minimum wage.

When you look at the population that would be affected by increasing the minimum wage, it’s not the stereotype of the teenager working after school just so that they have enough money to buy video games. The vast majority of the folks that would be affected by an increase in the minimum wage are adults 20 or older. Many of them work full-time, primarily women. About a third of them are married. About a quarter of them have children.

Outside of raising the minimum wage, what are some other things that could help to raise wages?

Other things like the Obama administration’s proposed rule change regarding overtime, raising the threshold under which someone is automatically eligible for overtime — [all] that’s going to raise wages. Strengthening collective bargaining, making it easier for workers to form a union and negotiate collectively — that would raise wages. Targeting full employment by the Federal Reserve (in other words, getting the unemployment rate down so low that employers have to start fighting to get the staff that they need by bidding up pay in those positions) — that’s another thing that would raise wages.

The reality is that over the last 35-plus years, the only time when the vast majority of Americans have experienced an actual increase in hourly wages was in the late 1990s, between 1996 and 2000, when we had such a tight labor market, when unemployment was so low that we had this experience of employers bidding up wages. That lifted pay for folks across the wage distribution, but particularly folks down at the bottom who were in the 10th, 20th, 30th percentile.

So how does this dynamic impact the government’s spending at large?

Basically right now we have a situation where a lot of workers in retail and other industries where folks are getting paid wages that are so low that they have to supplement their income by using food stamps or other public assistance programs. Essentially, those are dollars that are being provided to those workers through the government, through the taxpayer.

If we raise labor standards or if we targeted full employment, Wal-Mart and those other employers would have to raise higher wages, and that would mean that the folks receiving those benefits would probably see their benefits decline. But because they’d be making more on the job, on net they’d still be better off. So the money that the government would not be spending then on food stamps could be taken and used for other purposes or could even be used to strengthen those programs that target poverty and try to lift people up who are struggling.