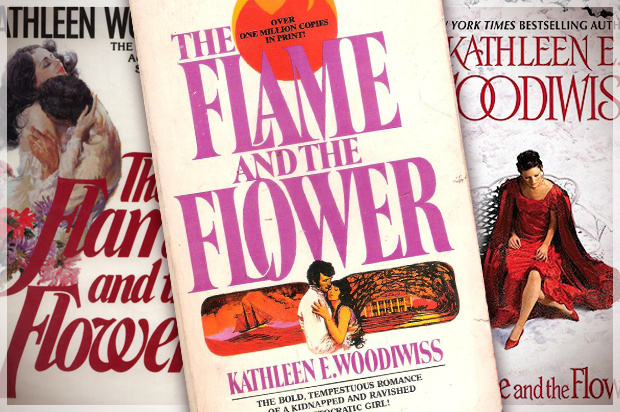

Forty-four years ago, in the winter and spring of 1972, two publications debuted just months apart that might seem at first glance to have nothing in common. In January 1972 — a time when the Equal Rights Amendment was big news — the first issue of Gloria Steinem’s Ms. magazine appeared, and sold out in eight days. Then in April 1972, “The Flame and the Flower” by Kathleen Woodiwiss caused an immediate sensation by opening the bedroom door. It also opened a new era of highly popular romance narratives where sex could be part of the story.

For me this spring also marks my own personal publishing milestone: My 25th romance novel, “Love After All,” will be out in April. With that anniversary coming up, and with Valentine’s Day upon us, the moment seems right to reflect on how romance novels picture love, and how they picture women. When Ms. and “The Flame and the Flower” hit the stands in 1972, their depictions of women were worlds apart. That would soon change.

Forty years ago public discussion was just beginning about equality in the workplace, domestic violence, sexual harassment, reproductive rights and other issues affecting women. Romance novelists quickly joined the discussion, grappling with these same issues through the lens of love.

In Woodiwiss’ “The Flame and the Flower” the orphan heroine, Heather, is out and about one evening in 19th-century London when a man attempts to rape her. She kills him and runs away, getting lost near the London docks. There the captain of a ship, the hero Brandon, mistakes her for a prostitute, captures her and sails off with her to South Carolina. On board ship Brandon rapes her, whereupon he realizes she’s a virgin.

Long story short: Heather gets pregnant, she and Brandon are forced into marriage, trials and tribulations ensue and they eventually get their Happily Ever After.

Heather has no understanding of her sexuality and no power of consent. She has two bad choices: First, she can either be raped or kill her sexual aggressor; later, when Brandon rapes her, she can resist or learn to love her rapist. From this unpromising beginning, romance narratives quickly shifted in their exploration of women’s sexuality and the nature of consent.

In early 1970s romance novels “no” sometimes meant “yes” and a rapist could figure as a hero. By the end of the 1970s “no” meant “no” and a rapist could no longer fill the hero slot.

In those early romances heroines were virgins and heroes had a lot of sexual experience. Those dynamics, too, changed quickly. Well before “Sex and the City,” romances validated women’s sexuality and curiosity. I remember loving Beatrice Small’s “Skye O’Malley” (1980), whose title heroine was luscious and lusty.

Today heroines are allowed to have sexual desire and are informed about consent. If they make bad choices, they learn from their mistakes. It’s even possible to have a virgin hero, such as James in Diana Gabaldon’s “Outlander” (1991).

Over the years, and long before Barbie got her new body, romance novels also changed the portrayal of women’s bodies. Early on heroines tended to be normatively slim with perky breasts. Soon enough that changed when the full-figured Amelia Peabody in Elizabeth Peters’ “Crocodile on the Sandbank” (1975) strode onto the stage. Today heroines come in all shapes and sizes.

Romance novels haven’t just reflected changing ideas about women. They’ve also long been gay friendly and featured characters from all ethnic backgrounds. Harlequin published Sandra Kitt’s African-American romance “Rites of Spring” in 1984. In today’s romances, characters of various ethnicities have become commonplace.

When I put “The Flame and the Flower” next to a romance from 2016, the most striking difference is in the heroines themselves. Forty years ago a heroine was either an orphan nobody like Woodiwiss’ Heather or maybe a secretary. Today heroines are firefighters, travel agents, lawyers and doctors; deep-sea divers, police officers and captains of industry. Again, Skye O’Malley comes to mind here, leading her own fleet of ships in that 1980 book. Romance writers have long dreamed big.

Question: Who also benefits from women discovering their sexuality, liking their bodies, and becoming worthy breadwinners with satisfying careers?

Answer: Their lucky partners.

For many people, Valentine’s Day is a one-day event. For readers and writers of romance novels, it’s Valentine’s Day every day. Romance novels don’t ask the old question: “Can women have it all?” The premise of the narrative is an obvious “yes.”

Julie Tetel Andresen is a professor in the English department and chair of the interdepartmental program in linguistics at Duke University. Her most recent romance is “Knocked Out” (2015). Her most recent academic book is “Languages in the World. How History, Culture and Politics Shape Language” with Phillip M. Carter (January, 2016). Follow her on Twitter @JTAbooks.