If the vague, yet oft-touted, religiosity of presidential wannabes remains a factor in elections these days, there may be a good historical explanation for why that is, beyond the percentage of churchgoers who vote. We’re talking George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, not that either of those two gentlemen cared much for praying and such.

Our country began celebrating George’s birthday when he first entered office, and still does despite the fact that, since 1971, the generic Presidents’ Day never falls on either Lincoln’s (the 12th) or Washington’s (the 22nd) February birthday anymore. Thank Congress for that. The third Monday in February apparently only belongs to the advertising industry.

Washington took his final breath in the waning days of the 18th century. He was mourned nationally on what would have been his 68th birthday, in 1800, an official day of fasting and prayer not to be repeated until 1865. Artist David Edwin’s commercial print “Apotheosis of Washington,” publicized later in 1800, shows the placid Hero rising to heaven, a “wreath of immortality” above his head. Eulogist Henry Lee, a major general and the father of Robert E. Lee, suggested that if the American Union was to prove immortal, it would be because Washington looked down upon and blessed it.

The three outstanding traits assigned to the much lamented “founding father” (the term is actually of 20th-century vintage) were his incorruptibility, courage and fairness. In life, the towering (6-foot-3) professional soldier was obviously imposing; effectively turned into a religious icon in death, he was frequently referred to as the “instrument of heaven.” This holy designation was what sealed Washington’s place as the moral exemplar of all time. Jefferson possessed the beautiful and empowering turn of phrase, Madison the glowing acumen of a constitutionalist; but Washington alone remained politically (as he was in war) bulletproof. Thanks to the invention of photography, the martyred Lincoln can still evoke tears, but among the most esteemed of presidents Washington looks best, as it were, in marble.

That earliest of presidential myths, George Washington’s “I cannot tell a lie, father…” comes courtesy of the Rev. Mason Locke Weems, in a book published in 1800, and meant to inculcate patriotism––and enrich the good parson, at 25 cents a pop. “A History of the Life and Death, Virtues and Exploits of General George Washington, Faithfully Taken From Authentic Documents” was dedicated to the national father’s widow, Martha, on Washington’s first posthumous birthday, at the behest of “orphaned America.”

Washington saw his birthday celebrated during his lifetime, and stood by as his presidency was clothed in robes of quasi-royalty (certainly by modern standards), despite the pride a majority of his countrymen took in the republican ideal that dictated against ostentatious display. The Washington myth propounded by Weems took many forms beyond the cherry tree, much of which was couched in religious language. As that instrument of God, his “great name” was all his soldiers need utter in order to find courage, fight and save America from ruin. Washington was, wrote Weems retrospectively, “him, whom heaven, in mercy, not to America but to Britain and to the world, had raised up to found here a wide empire of liberty and virtue.” As a soldier, he was “the first on the field and the last off.” He proved “that virtue is the soul of courage.” Editorialized the author: “The next duty to piety is PATRIOTISM.”

The good parson’s Washington retained his heroic character as president by existing above partisanship when other mortals could not. The “unutterable curses of FACTION and PARTY, rose often in the mind of Washington, and shook his parent soul with trembling for America.” To honor his memory, then, citizens were urged to wake from all pettiness and “fly from party spirit,” which was “the only demon that can prevent favoured America from rising to the greatest and happiest among the nations.”

On the 100th anniversary of Washington’s birth, in 1832, “centennial balls” were held across America. Military posts saluted with the firing of 100 guns. That week, Congress was disappointed in only one instance, when the effort to convince the patriarch’s heirs to part with his remains, that they might be removed to the Capitol to go on permanent display, failed.

In his lifetime (and at no time after), Washington had his public detractors. Cold and aloof, he was at times irritable when the roar of adulation went silent–he craved notice. During the Revolutionary War, his leadership was on a number of occasions called into question and his explosive temper noted. When he retired from the presidency in 1797, the Philadelphia newspaper editor Benjamin Bache, a grandson of Benjamin Franklin, called for rejoicing, writing disrespectfully that “an able carpenter may be a blundering tailor; and a good general may be a most miserable politician.” Others pointed to his flawed humanity, more quietly, in private letters. But his integrity, his essential honesty in political life, was never called into question.

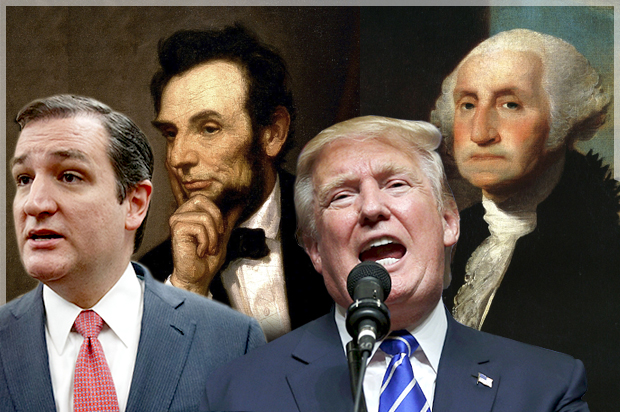

In the quiet classic, “Red, White, and Blue Letter Days,” the historian Matthew Dennis notes that upon Lincoln’s death in 1865, banners spelled out the new message as an unmistakable allegory: “Washington the Father, Lincoln the Savior.” Dennis points out the further absurdity of president worship in his characterization of the adorably campy 1881 oil painting by Erastus Salisbury Field, which shows the foremost Revolutionary commander standing with an arm resting on the shoulder of Lincoln, the two of them flanked by Civil War generals. It is jarring, of course, but just as revealing of the unconscious need of national mourners to populate a holy pantheon. Washington gave comfort to Lincoln, as the pair were joined to personify American freedom in the abstract.

The religiosity of patriotism is nothing new. Nor is Romantic biography, which has held sway ever since Parson Weems, and ever since Washington Irving in the 1850s published a five-volume biography of the man after whom he was named. Irving’s “Life of Washington” came to be the most widely owned nonfiction work in private libraries across America. “The fame of Washington stands apart from every other in history,” Irving pronounced, “shining with a truer luster and a more benignant glory.” He had already made waves, as it were, with a multivolume biography of the mariner Christopher Columbus, whom he painted in Washingtonian shades and Americanized.

Following Irving’s example, virtually every Washington biographer since has openly avowed that the man on whom they lavish praise had an average intellect and was educated merely to conduct the mundane business of colonial life. It was his passage through arduous trials, as in Greek mythology, which formed him as a genuine historical hero. Washington might be the nation’s pillar of strength, but he never quite rose to be the nation’s conscience–it was as if that honor providentially awaited the martyrdom of the unbeautiful, sublimely brooding Lincoln.

Irving’s “Life of Washington,” wrapped in moralizing clichés, served as a reminder, as all of Irving’s stories did, that time softened the emotions, and that whenever Americans went bathing in a backward glow, they could simply forget the partisan battles that were waged in the past. As the creator of a time-traveling Revolutionary dreamer named Rip Van Winkle some decades before “Life of Washington” appeared, it was Irving’s genius to feed the historical imagination, to leave his readers in awe of the supernatural. He could bend time, displace time, and make everything come out all right in the end.

Irving left a major mark on more than one national holiday. He virtually invented Santa Claus, and he gets extra credit for Halloween owing to a certain fictional character whose head was a pumpkin. All in all, he exploited a very human trait: the desire to fantasize a friendly unknown, even one of cosmic proportions. We situate “great” past presidents in the escapism of that earlier aesthetic. To do so reminds us of what is good in the world––because we certainly don’t need to be reminded of all that bodes ill or feeds anxiety. That’s why we put up with conventional politics.

The giants of our past take us by the hand. Sometimes, as with the kind of movie magic Daniel Day Lewis delivered in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln,” we can be made to believe our forebears are knowable. We perceive the danger in this brand of seduction, but so what, right? To believe in an American Golden Age is only truly dangerous when untrustworthy politicians who read too much presidential hagiography and consult too little good history use their minimal engagement with history to parrot back something about the superiority of the “traditional family” or the supposed economic benefits that attach to “a simpler time” before the nanny state. Students of history know different. Our ancestors were in no way better off. There is no such a thing as past perfection or Washingtonian virtue.

Oversimplification of history is a real concern. We only have to turn on the television to recognize that the chance to engage major problems is undermined by singular news stories that occupy the entire news cycle, by manufactured crises, and by politicians promoting apocalyptic fears and unbelievable promises at the same time. “Make America great again” is just the most blatant of such concoctions. Any politician who wants you to believe that there was a glorious America at some undesignated moment in the past, a stable and protected time that can be restored somehow, does a real disservice to the voter. Families will not “once more” be magically wrapped in a loving embrace before the hearth; political actors will not prove themselves to be interested in what’s best for all Americans.

That time never existed. Certainly not in the Age of Washington. The gifted Adams family, gathered round the hearth on wintry evenings in Quincy, Massachusetts, was beset by successive generations of suicides and alcoholics. One can joke that if Donald Trump had cut down the cherry tree, he’d make Mexico pay for it; or that Marco Rubio would lambaste Thomas Jefferson for knowing exactly what he was doing when he tried to change America and make it more like France. But the nonsense we hear out of the mouths of schoolyard bully presidential candidates and gossipy news organs was precisely why politicos ended up dead on dueling grounds; it explains, too, how gadfly columnists behaved throughout America’s so-called glory years in spreading lies and prompting the candidates’ surrogates to daily dispel them.

If Bernie Sanders wanted to make trouble for himself, he’d shame President Washington for being of the 1 percent, for gobbling up all the best frontier land and exacting steep rents from the poor folks who settled on it. He’d be right. Even putting aside the slave-owning that a gaggle of Virginia presidents was complicit in, we’ve had a lot more chief executives on the order of Chester Arthur and Warren Harding than those warranting a February holiday.

Parson Weems toyed with his generation, and the legend lived on. If George Washington could not tell a lie, then public servants with aspirations––for they had all heard the tale as youngsters––could be made to honor at least the ideal that was presented of the virtuous Washington. When an “outsider candidate” named Jimmy Carter ran for president in 1976, he predicated his entire campaign on a refusal to lie to voters, which was made credible by his well-known religiosity, and was especially refreshing in the wake of Watergate and Nixon’s resignation. His Washington-esque appeal wasn’t enough to salvage his administration after four inflationary years and 444 days of failure to rescue hostages to the Iranian Revolution.

President John Adams, the very first one-termer, was similarly constituted insofar as his vaunted personal honesty won him few friends. To his son, fated to be only the second one-termer, he wrote of the hopelessness of removing oneself from partisanship and relying instead on unbiased judgment: “You are supported by no Party. You have too honest a heart, too independent a Mind and too brilliant Talents, to be Sincerely and confidentially trusted by any Man who is under the Dominion of Party Maxims or Party Feelings: and where is there another Man who is not?”

Party politics ruined the chance of Americans enjoying “the good old days” a long, long time ago, friends. Hopefully, the lesson to be gleaned is not that honesty and talent won’t ever go over as well as a warrior mentality, or that the carpet-bombing politics of our present-day campaigners will continue to yield rewards. Anyway, Happy Presidents’ Day.