My MFA in nonfiction made me a novelist. On the one hand, spending two years practicing the art of sentence-making made me a more ambitious writer. On the other hand, I didn’t agree with the standards by which memoirs and personal essays were judged.

As James Wood recently wrote in a review of Lauren Groff’s “Fates and Furies,” “a novel that can be truly ‘spoiled’ by the summary of its plot is a novel that was already spoiled.” The same could be said of memoir: Any good book is much more than a litany of events. But nonfiction, it seemed from my writing workshops, was judged more by its plot than its language: what mattered was not the way a story was told, but how intriguing the events of the story were and how neatly those events all tied up together in the end. “Brave” was the highest—and most common—compliment a piece of writing could engender, which usually meant that the author had revealed personal information considered shocking or humiliating, followed by a clear-cut moral. We were supposed to be writing true stories, but this formula—confession, epiphany—was not at all true to the way I experience life.

By the end of my MFA, I was both weary enough of plot-centered critiques of writing and confident enough in my own use of language to believe I could at least attempt to write a novel. And what I discovered in the course of writing “Wreck and Order” is that I could communicate much more truth in fiction than I had ever been able to through personal essays. This is partly because I was no longer beholden to the often dull or inconvenient details of real life, but mostly because I could imagine truths other than my own.

Writing a novel requires close observation of both the inner and outer world, which allowed me to imagine my way into other people’s stories or into other possibilities for my own life. I had to listen to deeper layers of my brain, pay closer attention to what in real life are just passing rages or fancies, imagining what would happen if I acted upon them. As Jeanette Winterson once said, “I’m not happy for words to simply convey meaning. [They] can if it’s journalism and it’s perfectly all right if you’re doing a certain kind of record or memoir, but it’s not all right in fiction.” Rather, as she argues in her essay “Imagination and Reality,” the “true effort” of art is to “open to us dimensions of the spirit and of the self that normally lie smothered under the weight of living.”

The distance between reality (record or memoir) and truth (the rich, unseen underlayer of daily life) has widened in recent years, with the rise in reality TV; tell-all blogs; podcasts like “Serial” that turn real crimes into juicy murder mysteries; celebrity memoirs that sell for millions, while author income drops significantly overall. Anyone who’s watched an episode of “The Real Housewives” knows that just because something is real does not mean it is reflective of reality. Such deliciously ridiculous drama does not seek to depict life as it actually exists for most of humanity, but rather to use the titillating external details of strangers’ real lives as a distraction from the viewer’s own inner life.

The James Frey debacle revealed just how highly the public values confession, even at the expense of quality. Unable to find a publisher for his novel “A Million Little Pieces,” Frey decided to shop the same book around as a memoir. Random House purchased it, Oprah Winfrey extolled it, and it found millions of fans—until readers discovered the supposed memoir was largely fabricated and Frey instantly, dramatically fell from grace, with Oprah going so far as to invite him on her show to publicly excoriate him for “betraying millions.”

It’s odd that the exact same book—same sentences, same voice, same structure—could be judged so differently depending only on its genre. In his three-page acknowledgment of the lies in his memoir, now included in all editions of the book, Frey writes that he made things up because he wanted his book to have “the tension that all great stories require.” But a story doesn’t need drug rings, suicide and jail time to have tension: “Mrs. Dalloway” is about a woman giving a party; “Notes from Underground” is the misanthropic rant of a retired civil servant. If Frey were capable of writing a great story, he wouldn’t have had to claim his novel was true in the first place. The only reason Frey’s book found readers is because they believed he had actually lived through this unbelievable litany of hardships and depravities. The public’s obsession with confessionals risks lowering our standards for storytelling and making us largely blind to language.

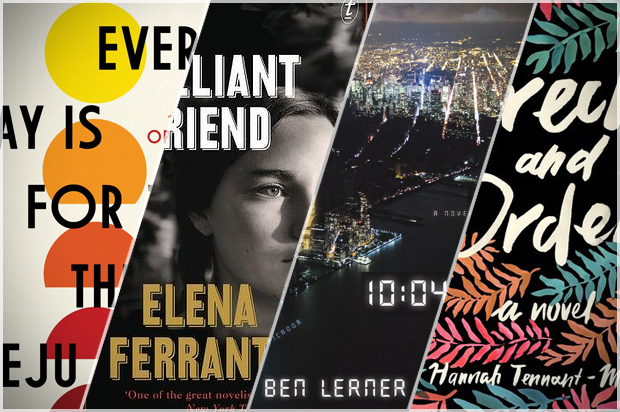

A welcome antidote to pop culture’s reality craze is the recent crop of popular novels that are both beautifully written and committed to depicting the parts of real life that cannot be readily seen or explained. Ben Lerner, Edouard Levé, Lydia Davis, Amélie Nothomb, Elena Ferrante, Eileen Myles, Janet Frame, Teju Cole, Ben Metcalf and Eimear McBride all reveal specific and often overlooked “dimensions of the spirit and of the self” as much through language as through plot.

Ben Lerner’s second novel “10:04” tells the story of a novelist named Ben struggling to balance life and art in the wake of a book deal for the novel we are currently reading. Teju Cole’s “Open City” chronicles “the constant struggle to modulate the internal environment” through his narrator’s observations of city life and conversations with strangers. The epigraph of Eileen Myles’ “nonfiction novel” “Cool for You” is taken from the title of a painting by artist and poet Antonin Artaud: “Jamais real, toujours vrai.” Myles is not concerned with depicting her life as a series of real events, but rather communicating how it felt to grow up poor and female and full of an inner power and joy that found no place in the outside world.

The emotional power of Elena Ferrante’s novels—particularly “The Days of Abandonment”—is so specific and convincing that the reader hardly doubts the veracity of the events that cause and result from these emotions. Yet it’s entirely possible that most or all of Ferrante’s plots are concocted. By keeping her identity a secret, Ferrante refuses to allow any discussion of “real” versus “make-believe” to impact the way her books are judged. “I very much love,” she has written in justification of her anonymity, “those mysterious volumes, both ancient and modern, that have no definite author but have had and continue to have an intense life of their own.”

Writers whose primary concern is a faithful depiction of the human heart and mind have a long tradition to draw upon, from Proust, Knut Hamsen, Sebald, and Henry Miller, to more recent classics such as Alice Munro’s “Lives of Girls and Women” and Norman Rush’s “Mating.” Although “Mating” is clearly not autobiographical—Rush is male and his narrator is female—the book feels true both to his character’s particular voice and patterns of thought and to the way the mind creates language in general. Munro has said that “Lives of Girls and Women”—which portrays a seemingly average teenage girl getting to know herself as she gains and loses friends, acts in school plays, loses her virginity—is an “autobiography in form but not in fact.” This is perhaps the best way to characterize the difference between the real and the true in writing. Truth in writing—whether fiction or memoir—comes from finding an original form that accurately reflects a particular person’s particular experience, whether or not the details of that experience are based on real life.

Edouard Levé’s “Suicide” is written in the second person, addressed to a friend of the narrator’s who committed suicide 15 years earlier. It certainly increases the intrigue of the novel to know that Levé took his own life soon after completing “Suicide,” but the novel’s power is self-contained. Levé’s nonlinear stream of recollections about his friend denies the reader the self-forgetful pleasure of the traditional novel: that of entering another world, elaborate yet comprehensible. Levé sees such collective sense-making as an anxious denial of the essential absurdity of our lives. So “Suicide” does not seek to explain how circumstances could make a person desire death, but only to illumine the particulars of that desire. As the narrator’s revelations about his friend’s inner life become increasingly complex, the reader comes to see “you” as an externalized form that allows the narrator empathic clarity about the most disturbed parts of his own being. The very fact that his friend is dead allows the narrator to have the kind of unchanging closeness with him that one often has with books, which allow one to feel less alone by virtue of feeling more connected with one’s self:

If you were still alive, would we be friends? I was more attached to other boys. But time has seen me drift apart from them without my even noticing. All that would be needed to renew the bond would be a telephone call, but none of us is willing to risk the disillusionment of a reunion. . . . I no longer think of them, with whom I was formerly so close. But you, who used to be so far-off, distant, mysterious, now seem quite close to me. When I am in doubt, I solicit your advice. Your responses satisfy me better than those the others could give me. You accompany me faithfully wherever I may be. It is they who have disappeared. You are the present. You are a book that speaks to me whenever I need it.

Consider, by contrast, the following passage from Catherine Millet’s memoir “Jealousy”—the follow-up to her bestselling “The Sexual Life of Catherine M.”—in which Millet agonizes over her husband’s affairs with younger women. Millet reveals, in the course of a page-long paragraph about her passing interest in plastic surgery, that her mother committed suicide when Millet was a child. When she tells her husband, “My mother’s death has broken me,” he responds, “What kind of cliché is that?”

Being caught in flagrante using a ready made formula only increased my feelings of helplessness and humiliation. But over the next few days I had decided that in fact I wouldn’t retract the word ‘broken,’ even if it was so often used incorrectly, hyperbolically, creating the reverse effect of what was originally intended, and making it sound somehow pompous. There is a reason why a commonplace is called common. When we use one, it is not just that we suddenly have a lapse of lucidity or intelligence or even of culture, which would otherwise enable us to make a more refined or appropriate choice of vocabulary, it is also that we need to feel part of something. When suffering from the shock which comes from joy or misfortune, human beings are not fitted for the solitude which extreme emotions often bring upon them, and so they try to share them, which usually means they must ‘relativise them,’ that is to say, play them down.

By the end of this treatise on “appropriate choice of vocabulary” and the human impulse to “relativise” emotions, the reader still has no clear sense of how Millet feels about her mother’s suicide or what, if anything, this suicide has to do with her pained relationship with her husband. We learn more in one sentence of Levé’s about both the precise nature of the narrator’s feelings for his dead friend and the complications of intimacy in general.

Let’s look at a second example: In the wake of learning that their husbands are having affairs with younger women, the writers of “Jealousy” and “The Days of Abandonment” have a nearly identical physical reaction: they lose control over their bodily movements. Here is how Millet describes the change: “Firstly, my emotional state was such that I could only move extremely slowly. Sometimes one’s heart rate increases to a point at which it seems as though the heart is banging against the walls of the chest and that what one hears is the sound of it doing so.” And here is Ferrante on the same experience: “I wanted my movements to seem purposeful, but instead I scarcely had control over my body…. In the car I had nothing but trouble: I forgot I was driving. The street was replaced by the most vivid memories of the past or by bitter fantasies, and often I dented fenders, or braked at the last moment, but angrily, as if reality were inappropriate and had intervened to destroy a conjured world that was the only one that at that moment counted for me.”

Millet may be describing real events from her real life and Ferrante may be inventing the life of an imaginary woman, but Millet’s awkward, stilted, and oddly generalized language merely allows us to gape at a version of reality we already think we understand. Ferrante, on the other hand, forces us into the unseen layers of that same reality. Just as her narrator’s belief in a coherent world of work and family is destroyed when her husband leaves her, Ferrante’s depiction of everyday life does not reinforce a common sense of the way the world is, but rather surprises the reader into new understandings.

Janet Frame decided to publish her novel “Towards Another Summer” posthumously because she felt it was too personal to be shared in her lifetime, even though her life story was already well known thanks to her bestselling memoir “The Angel at the Table.” Little happens in “Toward Another Summer”; the story’s momentum comes from the unusual, moving way the narrator’s mind struggles through ordinary human interaction. Fiction frees the writer to reveal not only the self as it appears to the outside world, but also the self that, as my narrator puts it in “Wreck and Order,” “I feel myself to be late at night when I can’t sleep and I’m all alone with the minutes passing, and I’m wide awake with thoughts I want to force the minutes to understand, but they are too fast, they pass and pass, and then pass again.”

Writing slows time down enough to force an awareness of secret thoughts from secret selves. A fictional narrator can be the person you fear you are, or the person part of you wants to become and parts of you wants to kill, or the person you were once for 30 seconds the one and only time you stood up on a surfboard, or the person you are in the gap between consciousness and unconsciousness at the moment you wake up in the morning, before your brain’s belief in your fixed identity starts bossing you around.

When I began writing “Wreck and Order,” I was writing the story of the person I feared I would become, and somehow, in the course of writing, it became the story of the person I still hope to be. Only fiction could allow me to bridge that distance, not with miraculous self-improvements and life changes (the drunken sex addict becomes a saintly Buddhist nun!), but by concretizing—through language, through imagined events—the invisible connections between seemingly disparate longings and personalities, times and places.

I don’t mean to imply that memoir is inherently limited. There are countless examples of memoirs that are not merely factually accurate, but also manage to reveal complex truths about how it feels to live particular facts—”This Boy’s Life,” “Name All the Animals,” “Darkness Visible,” “Survival in Auschwitz”—just as there are countless examples of novels that provide facile explanations of life solely through plot, without ever credibly depicting characters’ inner lives. Truth, in both memoirs and novels, does not come from relaying concrete events, but from giving language to the invisible, ineffable undercurrent of real life that makes every event much more than it appears to be.