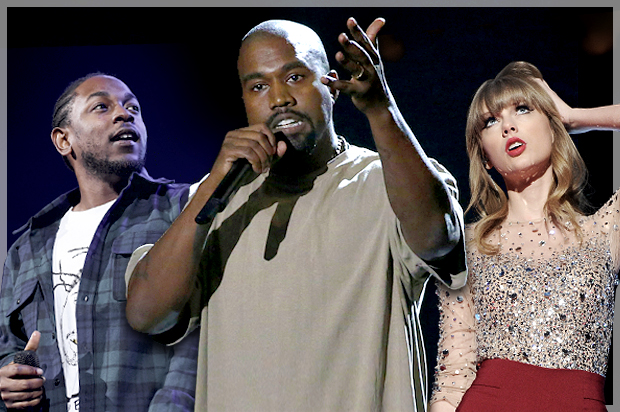

If you’re a gambling person, don’t bet against Taylor Swift at this year’s Grammys. Although many critics favor Kendrick Lamar to win album of the year for his critically beloved “To Pimp a Butterfly”—2015 winner of the prestigious Pazz and Jop poll—the 26-year-old pop star is widely expected by Grammy insiders to take home the evening’s top prize for “1989” instead. Pundits on Gold Derby are currently backing Swift by 50 percentage points. That would be Swift’s second win in the category after her 2009 win for “Fearless.”

History is certainly on Swift’s side. Recent best album winners like Daft Punk, Mumford and Sons, Arcade Fire and Adele all have something key in common—they’re all white. An artist of color hasn’t won album of the year since Herbie Hancock’s 2008 win, a problem that Kanye West called out last year when he nearly stormed the stage to interrupt Beck as he accepted a surprise win over Beyoncé. (To widen the frame of reference further, in the last 40 years, 12 of the album of the year awards have gone to artists of color.) Beyoncé’s self-titled visual album redefined the music industry when she released it without prior press in December 2013, but she settled for wins in the R&B song categories.

If Kanye once suggested that George Bush didn’t care about black people, the same can be said of the Grammy Awards, at least in recent years: The ceremony will continue to dismiss the musical contributions of people of color because the Grammys simply do not value black artists on the same level as their white peers. In a year that brought us #OscarsSoWhite and the continued conversation about racial inclusion at the Academy Awards, the public has yet to recognize that the Grammys have the same problem: They’re extremely white—and only getting whiter.

Each year, the Grammys present a stage that exhibits a post-racial ideal of diverse artists of varying backgrounds coming together for artistic collaboration. The show brought together U2 and Mary J. Blige in 2006 for a transcendent rendition of the Irish band’s classic “One,” as well as Ed Sheeran, Questlove, John Mayer and Herbie Hancock for a performance of Sheeran’s “Thinking Out Loud” last year. But even that utopian ethos is deceptive: Notice that Blige also offered backing vocals to Sam Smith in 2015 for “Stay With Me,” but the Grammys have yet to enlist Adele and Lady Gaga to jam out in the background of “Family Affair.”

That’s because the Grammys like their diversity when it has a white face at the center. In the history of the Grammys, only two hip-hop acts have ever earned album of the year—Outkast for “Speakerboxx/The Love Below” in 2004 and Lauryn Hill for “The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill” back in ‘99. A hip-hop album wasn’t even nominated until 1990, when M.C. Hammer’s “Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em” broke that glass ceiling for rap artists at Grammys. Since then, album of the year has passed over far more deserving records—2Pac’s “All Eyez on Me” and Jay-Z’s “Reasonable Doubt” in 1997—for fare like Celine Dion’s “Falling Into You.” If you have to ask whether Jay-Z or 2Pac even made the album of the year shortlist, clearly you’ve never seen the Grammys.

In fact, the Grammys didn’t even recognize hip-hop albums as their own separate competitive category until 1996 — to use a reference a Grammy voter might recognize, that’s a full decade after the Beastie Boys released “License to Ill.” Naughty by Nature’s “Poverty’s Paradise” became the first-ever rap album winner; before then, the group had only previously given awards to rap singles, not entire LPs. Since Eminem won his first rap album Grammy in 2000 for “The Slim Shady LP,” white artists have dominated the category. Although white artists account for just 11 percent of rap nominees in the past 16 years, acts like Eminem and Macklemore make up 35 percent of the category’s winners.

As the CBC’s Jesse Kinos-Goodin points out, it’s not just that the Grammys favor white artists overall, but that they almost always win any time they are nominated for a rap album award, too. “Kanye is the only rapper to ever win the award against a white artist (he beat the Beastie Boys in 2005 and Eminem in 2006),” Kinos Goodin writes. Perhaps that’s the reason why Eminem currently holds the record for most rap album awards—with six victories (over winless artists like Nelly, Mos Def, Common, the Roots, and Childish Gambino). The past two winners—Marshall Mathers (2015) and Macklemore (2014)—have both been white.

A couple of years ago, Macklemore stoked the flames of controversy by apologizing to Kendrick Lamar of “robbing” him for the best rap album award via a text message after he left the stage, rather than calling attention to the Grammys’ double standard in his speech. (The rapper—née Ben Haggerty—then reposted the exchange to his Instagram.) The apology, I’m sure, was well-intentioned, but Haggerty missed the point: Because the Grammys seem to believe that white artists sell (and black ones don’t), the awards are designed to rob everyone who doesn’t look like Macklemore.

As Salon’s Brittney Cooper told the Los Angeles Times, “Black stars are not seen as crossover stars and are often relegated to traditionally black categories.” This means that Kanye West—one of the most dominant and acclaimed musicians of the past decade—has never won an award outside the Rap and R&B genres. This would be less of an issue if those wins were on the same playing field as prizes like album or record of the year, but genre is treated as a lesser phenomenon, so much so that the Grammys don’t even air the presentation for rap album during the ceremony. They’re pushed to an awards banquet held earlier in the day.

The group’s disrespect for genres specific to non-white musicians was particularly clear in 2012, when the Grammys decided they didn’t need to be giving so many awards to people of color. “They decided to siphon off 31 jazz, world music and Latin-centric categories from the Grammys,” wrote Rolling Stone’s Raquel Cepeda. Latin jazz artist Bobby Sanabria called it “subtle form of racism,” protesting the decision along with musicians Paul Simon, Herbie Hancock, and Carlos Santana. The Grammys would save face by bringing back its Latin jazz award—at the expense of all the other musicians who got shown the door.

What’s unusual about the Grammy’s tortured relationship with genre is that historically, this wasn’t always the case. In the 1970s, revered R&B and soul singer Stevie Wonder won three album of the year awards, while Lionel Richie, Michael Jackson, Quincy Jones, Natalie Cole and Whitney Houston all took home the same prize in the next two decades. Their groundbreaking wins were reflective of a music industry where artists of color were gaining increasing amounts of radio play. Research from Vocativ shows that in the late ’90s and early 2000s, when rap ruled the airwaves, the Billboard Hot 100 was evenly split between musicians of color and white artists.

As research from Vocativ shows, that diversity peaked around 2003—rapidly declining in the years since. Today, mainstream radio is the whitest that it’s been in 40 years, as over 80 percent of artists on the Billboard Hot 100 are Caucasian. If it seems Grammys have followed suit, that disguises an important fact: The success of artists like Stevie Wonder and Natalie Cole were always outliers. At the apex of diversity, non-white musicians accounted for less than 10 percent of Grammy nominees—despite the fact that in 2000, people of color made up around 30 percent of the population.

As the industry has become whiter, so have the Grammy Awards. These days, the Grammys like R&B, hip-hop, jazz and Latin-inspired music best when they have a white person to vote for. In 2000, Santana won his first album of the year award after his Rob Thomas-sung “Smooth” went No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 for 12 weeks. After being nominated twice, Ray Charles nabbed a posthumous award for “Genius Loves Company,” a duets album that features a roster of the whitest people ever: Michael McDonald, Van Morrison, James Taylor, Bonnie Raitt and Diana Krall. Herbie Hancock won his 2008 album of the year trophy for singing Joni Mitchell covers.

When it comes to the nominations, at least, this year represents a modicum of progress: 2016 is the first time since 2005 that people of color boast the majority of album of the year nominees—the Weeknd, Alabama Shakes and Kendrick Lamar all earned bids. But not a single non-white artist is favored to win in the lead categories: In addition to Swift’s presumptive album win, she’s also expected to earn song of the year over Wiz Khalifa’s “See You Again”—which was the bigger hit. Record honors will likely go to the Bruno Mars-sung “Uptown Funk,” which feels like something. However, it’s Mark Ronson’s song—Mars is just the vocals.

Seven years ago, Kanye famously started this debate about who wins music awards and why when he interrupted Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech during the 2009 VMAs, arguing that Beyoncé deserved the honor. The public backlash made West a pariah in the music industry, writing “Runaway” in response to his regret and self-loathing over the incident (it’s the closest you’ll get to Kanye apologizing). But close to a decade later, history is repeating itself, as Swift is poised to win yet another award over more deserving black artists. If Kanye snatches Taylor Swift’s microphone on Sunday, it’s time to listen to what he has to say.

You might hate Kanye West, but you have to admit that he’s been right all along.