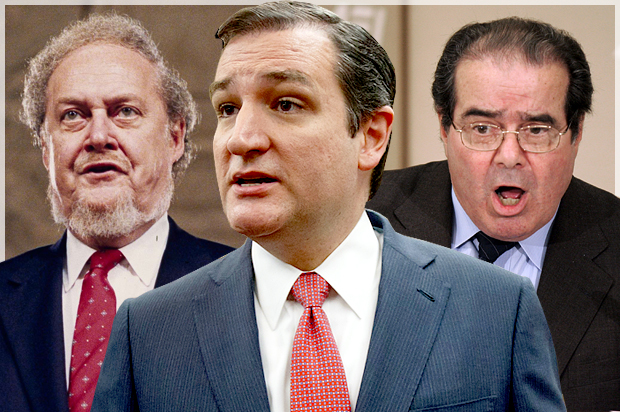

“Constitutional hardball.” That’s the term for what we’re seeing now in the GOP’s apparent staunch refusal to allow President Obama to fill a Supreme Court vacancy following Antonin Scalia’s death. And the one good thing about their refusal is that it brings the concept of constitutional hardball out into the open so that we can get a much better fix on what they’re up to—and what they have been up to for quite some time now.

The term was coined by Mark Tushnet in a 2004 paper of the same name. As he explained:

[I]t consists of political claims and practices–legislative and executive initiatives–that are without much question within the bounds of existing constitutional doctrine and practice but that are nonetheless in some tension with existing pre-constitutional understandings.

Of course, the Senate can refuse to vote on a presidential nominee; there’s nothing in the Constitution that specifically prohibits it. It’s just never been even considered, much less done, before. That’s some tension, all right! Could it be because of Obama’s race? Or just because he’s a Democrat? Tushnet continues:

It is hardball because its practitioners see themselves as playing for keeps in a special kind of way; they believe the stakes of the political controversy their actions provoke are quite high, and that their defeat and their opponents’ victory would be a serious, perhaps permanent setback to the political positions they hold.

Let’s see, Roe v. Wade, the Voting Rights Act, Citizens United, executive orders on climate change and immigration, just to name a few–yes, I’d say the stakes are high. As for “a serious, perhaps permanent setback,” that might be harder to say, but it’s certainly something that conservatives believe.

So, there’s really no question this is the sort of thing that Tushnet was talking about. In fact, it seems to me an even more clear-cut example than ones he cites in his paper, such as Democrats’ filibuster of specific judicial nominations in 2002-2003, mid-decade redistricting efforts in Colorado and Texas and the impeachment of President Clinton. Yet, for whatever reason, Tushnet only told the New York Times that it “probably” qualified.

Constitutional Hardball in Transition Periods

We’ll return to what he said, but first I want to dig a bit deeper into the concept and how to understand it. At one point, Tushnet writes, “My suggestion is that constitutional hardball is the way constitutional law is practiced distinctively during periods of constitutional transformation,” such as that which occurred during the New Deal. Constitutional transformations replace one constitutional order with another one, each involving a set of assumptions about fundamental institutional arrangements, “the relations between President and Congress, the mechanisms by which politicians organize support among the public, and the principles that politicians take to guide the development of public policy.”

As one illustrative example, Tushnet notes:

[P]rior to the New Deal, Congress initiated legislation subject to modest review by the President, whereas after the New Deal the President initiated legislation subject to modest review by Congress. And, during the transformative period when Franklin D. Roosevelt was attempting to construct a new constitutional order, his efforts to seize the legislative initiative were understood to be challenges to settled pre-constitutional understandings about the relation between President and Congress–and, as such, revolutionary.

While constitutional transformations may often occur relatively rapidly, this need not be case, Tushnet argues. In fact, he believes, “the concept of constitutional hardball does seem to describe a lot of recent, that is, post-1980, political practices. The reason, I believe, is that we have been experiencing a quite extended period of constitutional transformation.” The result is an “extended period in which political leaders played constitutional hardball. Indeed, it might come to seem as if constitutional hardball was the normal state of things rather than a symptom of the possibility of constitutional transformation. Transformation might seem like an ever-receding light at the end of the tunnel, and constitutional hardball the way politicians play day-to-day politics.”

There is, of course, a profound irony here: those trying to transform the constitutional order call themselves “conservatives,” even as they drive the process of striving for radical constitutional transformation. Liberals play hardball, too, of course, as Tushnet describes it, but the prime example he gives, mentioned above—the judicial filibuster of Bush appointees in 2001-2003—was a clearly defensive move, was turned to reluctantly, and was deployed against a limited number of targets. There was, throughout the process, a prudential conservative element in the Democrat’s thinking, which made good sense: they were trying to (re-)normalize things, trying to appeal to traditional notions of comity. Even if they had to take an extraordinary action in order to do so, they wanted their extraordinary action to be as reasonable and restricted as possible, while still achieving their goal—which was inherently a limited, defensive one.

The Case at Hand

With all this in mind, let’s return to what Tushnet told the New York Times:

The argument for calling it hardball is that there might be a reasonably settled understanding that it’s undesirable for the Supreme Court to operate ‘too long’ without a full complement of judges, and, as a result of that understanding, that the Senate will consider nominations sent to it reasonably far in advance of a presidential election.

But I believe what’s going on here is potentially much more radical than Tushnet’s description allows. The actual settled understanding is much clearer, and has nothing to do with presidential elections. That’s just a convenient ruse Republicans are using in their propaganda war. The Constitution (Article II, Clause 2) says the President “shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, judges of the Supreme Court….” To repeat: “shall nominate.” Not “may nominate.” It is a presidential duty, an obligation of the office, not a presidential right, which some may contest because they do not like him personally. It’s a duty of his office as long as he’s in office. There is no cut-off date. Thus, what Republican senators have almost immediately said is that President Obama should not do his duty.

To further underscore what the settled understanding is, we can look to the historical record. Since the time of George Washington, 196 nominations have been made, with 160 confirmations, while 36 declined, withdrew or were defeated,. Of those 160 confirmations, 10 were confirmed the same day they were nominated, 53 within a week, and 88—more than half—within a month. Only six nominees have taken more than three months to get a vote. Of these, two were rejected, one withdrawn and three confirmed. Only one nominee took more than four months for a vote—Louis Brandeis, who was confirmed 47-22. These last six examples represents the outer limits of delay, compared to the 11 months that Obama has remaining in his term. He could appoint three of the most contentious nominees ever in the time remaining.

While it’s true that the process has grown more intensive in the television age, the basic understanding has not changed. Since Richard Nixon took office, the average time from submission to vote has been notably longer than in the pre-television era, but it’s still only a fraction over 60 days, the longest being 114 days for Robert Bork. Again, we are nowhere near to any sort of time limit, other than the time limit that Obama should never be allowed to act as president at any time whatsoever.

But that view of theirs is entirely at odds with the universal understanding of what the office of the president entails. So what we have here is not a situation which is “probably” constitutional hardball. It is constitutional hardball on steroids. They want to cripple the president—at least until they control the Oval Office again, at which point, well, who knows? Because this is where I think Tushnet’s argument needs some refinement. I think he’s absolutely right about the prolonged period of constitutional transformation and constitutional hardball, but for whatever reasons, conservatives and Republicans have been unable to clearly formulate the constitutional order they wish to achieve, beyond simply keeping Democrats out of power. If they have the White House, they’ll make it as powerful as possible. If they don’t, they’ll cripple it. This is not a recipe for a constitutional order, it’s a recipe for constitutional disorder—and incoherence in terms of defending it. And they’re only getting better and better at it over time.

Oh, and just in case you might think being in an election year matters, at SCOTUSBlog, Amy Howe reports that “The historical record does not reveal any instances since at least 1900 of the president failing to nominate and/or the Senate failing to confirm a nominee in a presidential election year because of the impending election,” and then goes on to describe the record. Woodrow Wilson actually nominated two justices in 1916. Both were confirmed. So the idea that a president should hold off and “let the people decide” has never been taken seriously in practice. The people already did decide when they voted in the previous election.

Confusion, Inc.

Of course, conservatives and Republicans have gone all out on obscuring the issue. It’s what they do. And Media Matters has been going all out in batting them down. For example, they highlight Hugh Hewitt on CNN making up a new rule, “Lame ducks don’t make lifetime appointments.” And just to be clear Hewitt explicitly was framing it as a sort of marching order for the entire GOP:

If I were a Republican, whether the majority leader all the way down to the county clerk and every nominee, I would say very simply, no hearings, no votes. Lame ducks don’t make lifetime appointments….

It’s a nifty rhetorical contrast—lame duck vs. lifetime appointment—but it’s utterly without substance, since “lame duck” is a term referring to someone who has either lost or not run for re-election, and is simply serving out “dead time,” waiting for their successor to take office. It is simply ludicrous to refer to a two-term president in their last year in office as a “lame duck”: they have no elected successor, and all the normal responsibilities of their office still require their attention—including the appointment of Supreme Court justices.

The CNN host Dana Bash tried to question this canard, but Hewitt easily danced away into spinning further irrelevancies:

DANA BASH: And he’s a lame duck even a year out?

HEWITT: Easily. The last time — Justice Kennedy has been referred to a lot — was nominated in November of 1987 after Judge Bork had been blocked. That vacancy occurred in June of 1987. So there is no precedent. And I would simply add, the base will not forgive anyone. Senators will lose their jobs if they block the blockade. There should be an absolute blockade on this. And [Sen.] Patrick Leahy [(D-VT)], who was your guest earlier, voted 27 times to deny a vote or a hearing to Republican nominees between 2001 and 2003. Patrick Leahy created the conditions that he was decrying right now.

I’ll have more to say about Bork below, and while it’s true that Leahy took unusual steps—it’s the first example of constitutional hardball that Tushnet considers in his paper—his actions were all directed against specific nominees who had been named, and deemed too extreme or otherwise unfit. Neither Leahy nor any other Democrat sought to block all Bush nominees… none of whom were to the Supreme Court. Nor, of course, did anyone dream of telling Bush he couldn’t make such nominations in the first place. That’s four key points of difference between what Leahy did and what Hewitt—and others—are calling for now.

So what you see here is a typical performance of ill-informed conservative outrage, which seems to help fuel the dynamics of constitutional hardball in a way that’s quite satisfied to never settle down into a new constitutional order, but simply to move from one crisis formulation to the next, playing hardball all the way.

Hewitt is only one voice among many, and Media Matters comes to the rescue again, with a sort of roundup piece on various other false comparisons that have been floated. These include the mischaracterization of Senator Chuck Schumer’s objection that Justices Roberts and Alito had provided vague, inadequate and misleading testimony—not a call to refuse to consider them. Similarly, both Obama and Clinton joined the filibuster against Alito, after he had gone through confirmation hearings, and they laid out their reasons objecting specifically to him, not to anyone that George W. Bush might have nominated.

Another early favorite trope is to invoke the spectre of Robert Bork. But, as Media Matters points out, the Bork comparison is wildly off the mark, since Bork got a full hearing before the judiciary committee, and an up-or-down vote before the full Senate. He was rejected, just as 10 other nominees before him had been. There was nothing new, unusual or unprecedented in that. What was new was the degree of pubic scrutiny in the television age–but the problem wasn’t TV, it was Bork himself. As examples of his extremism, Media Matters cites an NPR report [emphasis added]:

He wrote an article opposing the 1964 civil rights law that required hotels, restaurants and other businesses to serve people of all races.

He opposed a 1965 Supreme Court decision that struck down a state law banning contraceptives for married couples. There is no right to privacy in the Constitution, Bork said.

And he opposed Supreme Court decisions on gender equality, too.

If Obama nominates someone as out of step with the American people as Robert Bork was, the GOP senators should have no problem voting against that nominee. Just let the process go forward, as the Founders intended.

Another View of Systemic Failure

If we want a clear view of what’s happening that encompasses all this foolishness, and bears some relationship to Tushnet’s concepts of constitutional hardball and constitutional transformation, it’s helpful to turn to Ian Millhiser, Think Progress blogger and author of the book “Injustices: The Supreme Court’s History of Comforting the Comfortable and Afflicting the Afflicted.” He doesn’t use Tushnet’s terms, but discusses similar dynamics, along with the political fray I’ve just touched on, and he’s got his eye on how things connect. For example, he notes how uniquely obstructionist Mitch McConnell has been as majority leader:

In the 13 months since McConnell became majority leader, the Senate has confirmed exactly 2 judges to federal appeals courts — and one of those two, Judge Kara Farnandez Stoll, was confirmed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, a largely apolitical court that primarily deals with patents. By comparison, the Senate confirmed six of President George W. Bush’s appellate judges, eight of President Bill Clinton’s, and 10 of President Ronald Reagan’s during the same 13-month period in each man’s presidency.

Both the point he’s making and the way he’s making it stand in stark contrast to the farrago of nonsense that the right is spewing, and much of the media is recycling as if it were the least bit credible. But Millhiser also argues that Democrats would behave quite similarly if the shoe were on the other foot. I don’t quite believe that—as I’ll explain below—but the reason he says so is vitally important.

No, the Supreme Court vacancy crisis cannot be laid solely at the feet of Mitch McConnell. Rather, it is another manifestation of the same broken constitutional system that gave us the last government shutdown. When different parties control different branches of government, our system requires consensus to prevent a breakdown of governance. But the two parties now have disagreements that are so fundamental that such agreement is impossible.

The argument Millhiser is making is actually two-fold. First, that we have a systemic failure of the constitution, a failure common to all presidential democracies, as he discusses in the 2013 story that he links to, written at the time of the government shutdown:

As Yale political scientist Juan Linz explained in 1990, the chief executive in a presidential system has a “strong claim to democratic, even plebiscitarian, legitimacy” as the only national official elected by the nation as a whole, but an opposition-controlled legislature can also claim democratic legitimacy as the winners of their own elections….

When the president and the legislature reach a truly unresolveable impasse, Linz warned that the end result is often quite ugly. “It is therefore no accident that in some such situations in the past, the armed forces were often tempted to intervene as a mediating power.

Of course, there are two problems with this, at least, in America’s case. The first is the Senate. As Millhiser himself notes in another post, the GOP majority in the Senate represents 20 million fewer voters than the Democratic minority. Hence, “the party that represents a minority of Americans in the Senate should not pretend to have the will of the people on their side.” The other problem is the House, thanks to extreme gerrymandering in a small handful of states, such that Obama won a majority of votes in six of them, and lost narrowly in a seventh, while Republicans took House seats from those states by a 2-1 margin. Hardly an advertisement for democracy.

Still, even though the GOP legislative majorities don’t represent voter majorities, they still are legislative majorities, which can pretend to represent the people—and a gullible media gives them every form of support they could ask for.

Competing Judicial Visions

Second, Millhiser argues that we have two competing judicial visions that are irreconcilably different, between which there can be no middle way:

Simply put, there is no such thing as a consensus nominee that can unite the sort of people who view Justice Thomas as a hero with the sort of people who view him as a crank.

One vision, he explains, goes back to the New Deal era:

Beginning in the late 1930s, a national consensus began to form around the appropriate role of the judiciary in a representative democracy. As the Supreme Court established in United States v. Carolene Products and similar cases, the overwhelming majority of issues belong to elected officials. The judiciary should intervene when lawmakers violate an explicit right protected by the Constitution, or when they engage in invidious discrimination, or when they enact a law “which restricts those political processes which can ordinarily be expected to bring about repeal of undesirable legislation.” But outside of these narrow categories, the people would rule through their representatives….

As I explain in my book, “Injustices: The Supreme Court’s History of Comforting the Comfortable and Afflicting the Afflicted,” liberals remembered the dark ages prior to Carolene Products, when the Supreme Court routinely implemented a conservative economic agenda through its decisions, while conservatives cared more about erasing decisions such as Miranda v. Arizona or Roe v. Wade than they did about implementing economic policies through the judiciary.

While conservatives have long had a strong, if not totally dominant presence on the Supreme Court, it’s only during the Obama administration that conservative judicial activism to attack Carolene Products (a key feature of Bork’s outlook) has distinctly come to the fore:

NFIB v. Sebelius, the first Supreme Court case attacking Obamacare, was a direct attack on principles established by the Supreme Court more than 200 years ago. The Federalist Society — an influential conservative legal society whose members, at least until Justice Antonin Scalia’s recent death, included three Supreme Court justices — has become a breeding ground for plans to render federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency impotent. United States senators speak openly of restoring long-discredited legal doctrines that would invalidate the minimum wage and the right to unionize. Justice Clarence Thomas, a sitting member of the Supreme Court, embraces an interpretation of the Constitution that would strike down federal child labor laws and the same Civil Rights Act Bork once railed against.

What Millhiser doesn’t say here, but that needs to be noted, is that Chief Justice Roberts is not fully on board with this extreme agenda, although he’s deeply ideological in his own way, having had his sights set on destroying the Voting Rights Act since the early days of the Reagan Administration, as Ari Berman lays out in his excellent book, “Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America“ (Salon interview here). Simply put, there are different strains of conservative thought, so what we’ve seen recently has been the emergence of one powerful faction in particular: a faction that wants to take down the New Deal and the entire, much broader constitutional framework around it.

But this is not what Republican base voters care about—as Donald Trump so vividly reminds us. They are powerfully motivated by negative partisanship—whoever Obama nominates must be opposed—but they have no interest at all in losing their Social Security or their Medicare, and that is precisely where the attack on Carolene Products leads, though of course it would take some time to get there. What’s remarkable about Trump is that—without knowing any of this—he has made these hidden long-term agendas palpably relevant to the GOP base today, however incoherently it’s mixed together with other issues.

Two Sides Aren’t Mirror Images

This begins to get at one of the ways in which both sides are not mirror images in this fight. Millhiser is right to point out that structural, systemic features of our political system can have generally symmetric destabilizing effects—in a similar vein, Tushnet points out that either side (ideology) or party can engage in constitutional hardball. But there are reasons why conservatives and Republicans are far more likely to engage in it, with a much deeper passion and long-term commitment. The broad popularity of the New Deal vision is one underlying factor. It causes conservatives to rely on a great deal more indirection and deceit in their politics, and it makes them far more conscious of how tenuous their hold on power is, making them all the more ferocious in hanging on to it. Although Tushnet uses a different language, one could make the same point in terms of his observation about how the GOP/conservative constitutional transformation remains in limbo.

As the nomination debate swirls, there have been immediate calls in several quarters—from liberals like Rachel Maddow as well as from centrists—for Obama to appoint a moderate, centrist “consensus” candidate. Millhiser rightly shows that such hopes are ill-founded, if this is supposed to make matters easier, but it does reflect a genuine difference between the two sides. There is a consistent constituency for moderation and compromise on the Democratic side, a view commonly held in contempt by Republicans. They have concluded that Roberts is a traitor, to be used in attacks on one another on the campaign trail, because he failed the talk-radio zealotry test on Obamacare.

Hence, even Millhiser’s analysis falls short of fully integrating all the moving parts. The internal dynamics of the two sides are significantly different. As the would-be initiators of constitutional transformation that’s been in limbo, it is the conservatives who are prime movers in the realm of constitutional hardball. They’re the ones who want to radically change how things are done—even as they try to pin the tail on the Democratic donkey, instead. The attempt to prevent Obama from appointing Scalia’s successor is simply an extreme example of the very essence of what they’re all about.

Tushnet calls it “constitutional hardball.” But at times like this, it feels like constitutional beanball, instead.