Bernie Sanders’ historic 20-point win in New Hampshire has dramatically pushed the Democratic campaign in a direction none of the punditocracy expected. Clinton immediately tried to respond, in part, by refocusing her campaign around race—a move whose historical underpinnings, from the execution of Ricky Ray Rector to mass incarceration to “welfare reform” that left millions of children behind, were sharply criticized by Michelle Alexander in the Nation, due to the Clintons’ actual history.

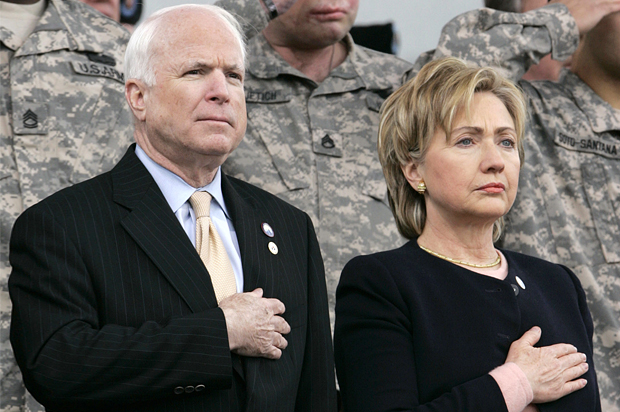

But we’ve also seen a predictable Clinton emphasis on foreign policy, taking aim at Sanders’ comparatively meager record—as we saw in the PBS debate in Milwaukee [transcript]—and trying to portray it as utterly disqualifying, rather than as yet another reflection of a profound elite/mass divide, symbolized by their starkly different views of elite elder statesman Henry Kissinger.

However, such a move also requires a massive case of amnesia—above and beyond her palling around with Henry Kissinger, that is—for Clinton’s hawkish differences with Obama as well as Sanders. It’s not just her Iraq War vote we’re talking about. Sanders is also far more in tune with Obama’s willingness to negotiate with enemies—a formerly bipartisan posture that traces back to John F. Kennedy (“Let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate”) as well as Teddy Roosevelt (“Speak softly and carry a big stick—you will go far”).

The fact that this is now seen as a soft, risky or fringe position by many in the establishment simply goes to show how badly the establishment has lost its way, on foreign policy, every bit as much as on domestic issues.

In an excellent piece at LobeLog, Eli Clifton shows how the Clinton campaign attacked and misrepresented Sanders’ call to normalize relations with Iran, how they similarly attacked Obama’s willingness to negotiate with adversaries in 2007/08, how Obama’s popular accomplishments—the Iran deal and restoring relations with Cuba—came directly out of the Obama/Sanders approach to negotiation, and how “Clinton megadonor Haim Saban may be one explanation for the tilt toward hawkish positions” she continues to espouse, despite Obama’s diplomatic successes.

None of this makes Clinton look particularly good in attacking Sanders. The words “whistling past the graveyard” come to mind. Meanwhile, the demise of Rand Paul’s presidential bid means the GOP is back to pure unfocused aggression as its consensus position. So one could cogently argue that, however inexperienced or seemingly uninterested Sanders might be—a characterization open to question, as we’ll see—he is still the best choice on foreign affairs as well as domestic: The conventional wisdom is wrong once again.

But that’s not how it’s been playing out so far in the media, as Max Fisher noted at Vox, “An issue that should be a strength for Sanders in the primary has become a weakness.” A prime reason is that donor influence is only part of a more general problem of elite culture when it comes to foreign policy, lurking just beneath the surface when Sanders, quite rightly, questioned Clinton’s coziness with Henry Kissinger, perhaps the major, unexpected flash-point of Clinton’s foreign policy vulnerability.

Sanders called Kissinger “one of the most destructive secretaries of state in the modern history of this country,” pointed to his role in overthrowing Prince Sihanouk, creating the chaos that led to the killing fields where 2-3 million were butchered, and said, “count me in as somebody who will not be listening to Henry Kissinger.” To which Clinton responded snarkily, “Well, I know journalists have asked who you do listen to on foreign policy, and we have yet to know who that is.”

Sanders’ argument here is on extremely solid ground. Clinton’s ties to Kissinger are strong, including emails between them when she was secretary of state, as Ben Norton and Jared Flanery wrote about here in January. And as Greg Grandin, author of “Kissinger’s Shadow,” pointed out at the Nation after the previous debate, Kissinger’s record was not simply littered with wantonly bloody escapades, but with demonstrably failed, counterproductive ones that give the lie to his posture of hard-nosed “realism”:

Pull but one string from the current tangle of today’s multiple foreign policy crises, and odds are it will lead back to something Kissinger did between 1968 and 1977. Over-reliance on Saudi oil? That’s Kissinger. Blowback from the instrumental use of radical Islam to destabilize Soviet allies? Again, Kissinger. An unstable arms race in the Middle East? Check, Kissinger. Sunni-Shia rivalry? Yup, Kissinger. The impasse in Israel-Palestine? Kissinger. Radicalization of Iran? “An act of folly” was how veteran diplomat George Ball described Kissinger’s relationship to the Shah. Militarization of the Persian Gulf? Kissinger, Kissinger, Kissinger.

The broad range of folly that Kissinger’s been instrumental in significantly buttresses Sanders’ argument that his judgment is better than Clinton’s: She looks at that catastrophic record of failure, and either doesn’t see it as the disaster it so clearly is, or else doesn’t understand the role of Kissinger’s horrendous judgment in it. Either way, it’s a profound indictment of her own judgment—and a much broader vindication of Sanders’ judgment that he proudly spurns it. Clinton’s Iraq War vote fits neatly and coherently into the broader pattern of Kissinger-generated follies in the region, while Sanders’ vote against it echoed elsewhere in his past record as well—though it’s not as well known. Since the question going forward is how to extricate ourselves from this mess, it certainly makes sense to choose someone who forcefully rejects the author of so many different facets of its genesis.

That said, we need to go back to Clinton’s snarky retort about Sanders’ lack of advisers. What’s going on behind the scenes here is most revealing, as Fisher explained:

Hillary Clinton has locked up much of Washington’s foreign policy expert community, and no one wants to defect to team Sanders for fear of being shut out of a Clinton administration for the next year four to eight years.

It’s not just a passive fear, either:

The Clintons are notorious for rewarding loyalty and punishing perceived disloyalty — no matter how slight or how long ago. Even when Clinton was part of the Obama administration, her State Department shut out quite a few people who had supported Obama.

If you’re a foreign policy professional, you remember that.

Hence, the back-and-forth exchange that boiled down to:

Sanders: You consult with a war criminal.

Clinton: So what? No one consults with you!

There’s an obvious problem here on both sides. On Clinton’s side it’s not just her indifference to Kissinger’s evil—which is bad enough—but, more insidiously, the way that the Clintons’ stress on loyalty systematically dampens criticism, thus contributing to the bubble mentality that has helped lead them astray in the past, most notably with the Iraq War vote (on top of the fact that Clinton sees Kissinger as mentor and guide). This is a systemic problem for the Clintons, analogous to their Wall Street/Super PAC/megadonor/speaking fees problem: it’s a cumulative problem of eroding judgment, and breeding blindness to the most precipitous of dangers. (An analogous systemic blindness problem on the political side prevented them from seeing Sanders as a serious electoral threat.)

But it’s also a problem for America more broadly, a devastating example of how elite crony politics sets itself up for disastrous systemic failures, suppressing or ignoring the very diversity of thought, depth of critical analysis and redundancy of fallback strategies and perspectives that ought to be characteristic of a mature, well-educated high culture. It’s almost as if the foreign policy establishment were trying to make the financial establishment look good by comparison.

On Sanders’ side the problem is his lack of a foreign policy team, and the difficulty of building one, given the reality of the Clintons’ influence—although, as Fisher indicates, there are knowledgeable anti-interventionist foreign policy experts ensconced in academia who could at least help get him through the primary process, and Mondoweiss has put together a list of dozens of possibilities—people like Stephen Walt, Andrew Bacevich, Phyllis Bennis, Juan Cole, Trita Parsi and Ali Abunimah—for Sanders to consider. There is, in short, at least a potential heterodox foreign policy bench for Sanders to draw on. Given that such talent exists, he would be wise to begin reaching out.

In fact, one very senior member of the foreign policy establishment has already spoken out in defense of Sanders: Lawrence Korb, who served as an assistant secretary of defense in the Reagan administration, and is now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and a senior adviser to the Center for Defense Information. In Politico recently, Korb penned a piece, “Bernie Sanders Is More Serious on Foreign Policy Than You Think,” in which he said:

In my dealings with him, and in analyzing his record in Congress over the past 25 years, I have found that Sanders has taken balanced, realistic positions on many of the most critical foreign policy issues facing the country…. Sanders certainly isn’t a foreign policy lightweight: In fact, given his long tenure in the House and Senate, he has more foreign policy experience than Ronald Reagan or Barack Obama did when they were running for office the first time.

Korb advised both men in their election campaigns, and was co-coordinator of Obama’s foreign policy team. Compared to their relatively paltry experience, Sanders “has been in Congress for the past quarter-century, voting on issues like the end of the Cold War, the rise of China, and the military interventions in Somalia, Kuwait, the Balkans, Afghanistan and Iraq.”

There’s a point to keep in mind here. Hands-on foreign policy experience has not been the rule for American presidents for a very long time. In our early years, when our size relative to the rest of the world made foreign policy inescapably central, the position of secretary of state became the primary mode of presidential succession. From 1800 through 1828, our third through sixth presidents—Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe and John Quincy Adams—were all former secretaries of state, all but Jefferson moving directly from the State Department to the White House. But those days are long gone, and it’s a much better guide to compare Sanders to more recent presidents, as Korb does in his piece.

As for the specifics of a Sanders foreign policy, Korb wrote that “it would be rooted in a number of key principles. First is restraint in using American force abroad,” including following the Weinberger/Powell Doctrine, which distilled the military’s lessons learned from the Vietnam War: “When the United States uses military force abroad, our objectives should be clear, we should be prepared to use all the force necessary to achieve those objectives, and we should know when they have been achieved.” It also requires an exit strategy—in advance.

Korb goes on to note that “Sanders’ military restraint extends to spending, too….There is no need for the United States to spend more than the next seven top-spending countries in the world combined, several of which are our allies, and more in real dollars than we spent annually on average during the Cold War.” Much more productively, in terms of building security, Sanders would push for ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, and the Law of the Sea Convention, and “He would, like many of our military leaders, treat climate change as a national security threat.” Last, but not least, Korb notes, “Sanders has demonstrated an admirable commitment to diplomacy.”

Korb also addresses the complaint that Sanders needs to get more specific, pointing out that other presidents haven’t been specific in advance (“Eisenhower said only that he would go to Korea; he had no specific plan for how to end the conflict there”) and have even reversed themselves (“Lyndon Johnson said specifically that he would not send American boys to fight wars in Asia”). Knowing how to respond to ISIS, or the problem of terrorism more generally, returns to what really matters most, the question of judgment:

It is hard to know what challenges the next president might face. That’s why, ultimately, judgment matters more than experience for a potential president. The presidents I have advised—Reagan and Obama, as well as George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State John Kerry—all showed great judgment in considering, but not bowing to, the advice of the foreign policy establishment.

I don’t think that Reagan was quite as wise as Korb does, though it’s true that, contrary to his image, Reagan rejected more rigid, hawkish decisions Korb points to: “choosing to withdraw from Lebanon and negotiate with Mikhail Gorbachev.”

The fatal counter-example to keep in mind is Lyndon Johnson. Particularly for progressives, if we have questions about Sanders on foreign policy, Johnson easily stands out as the great cautionary figure: a giant of activist government domestic policy, second only to FDR, his legacy has instead been defined by the Vietnam War, which he never wanted to fight, but proved unable to avoid. Moreover, the war contributed significantly to the Democrat’s sudden loss of power—they would only win the White House one time in the two decades after LBJ. Strong on domestic issues, weak on foreign affairs, the parallel seems obvious—and chilling.

But there are major differences as well. Johnson’s problem was not, at bottom, that he lacked experience. It’s that he deferred to an establishment array of experts whom he felt intimidated by, and he had no alternative vision of his own to guide him. But Sanders wasn’t intimidated into voting for the Iraq War, as noted repeatedly, and that judgment is reflected more broadly as Korb attests. So there’s a good initial reason to trust him to avoid Johnson’s mistake.

There are other reasons as well. Johnson’s Senate position as leader of the Democrats made him highly attentive to foreign policy issues, but almost entirely from a political point of view, which proved particularly misleading. He was conversant with the issues, but as a Senate strategist more than a global one. As historian and former Senate staffer Robert Mann describes in “A Grand Delusion: America’s Descent Into Vietnam,” the Democrat’s loss of the Senate in the wake of the Korean War profoundly shaped Johnson’s outlook. Much the same way that Senate Democrats like Clinton and Kerry “learned the lesson” from the Gulf War to support Bush Jr. with their Iraq War votes, Johnson and most of his cohort learned that they had to avoid another surprise like Korea. But the most knowledgeable senators—Mansfield and McGovern especially—were effectively sidelined in the process (Mansfield voluntarily, out of his sense of party/institutional loyalty).

Hence, Johnson and Clinton both had more experience, whereas “Sanders has operated during his time in Congress mostly on the sidelines on these issues,” Mann told Salon. “So, the only real record we have to go from are his votes against the Iraq War, which redound to his credit.” But beyond that, Mann thinks the record is thin. “I don’t see any evidence that he has been a leader on national security or military issues or has attempted in any way to educate himself on this during his time in Congress,” Mann said. “I think his lack of knowledge and experience on this matters shows during the debates.”

However, he notes, “As we’ve established, experience doesn’t mean one will make the right decisions, especially if that experience leads you to faulty conclusions. That was certainly Lyndon Johnson’s story and Hillary’s, too.” So, in the end, Mann asks, “What do we think would be Sanders’ degree of wisdom on issues like this?” And he answers, “I think we can safely guess that he would be skeptical of his military advisers’ advice and generally very reluctant to use military power. I suspect he would operate a bit more like Kennedy, post-Bay of Pigs, than Johnson in 64-65.”

Mann’s view of Sanders is less appreciative than Korb’s, who actually knows Sanders better, but he’s studied Johnson far more deeply, and doesn’t think Sanders would repeat his mistakes. Korb was quite clear on this:

I have no doubt that Sanders will be willing to challenge the foreign policy establishment, as Obama did on such issues. Does Sanders have the same amount of foreign policy experience as Hillary Clinton? Obviously not. But Bill Clinton had far less foreign policy experience than George H.W. Bush, and Obama had less than John McCain—and both presidents had effective foreign policies. If he is elected, I believe Sanders will also be able to attract a competent foreign policy cohort, just as Obama did—including many of the current Clinton team. With the right partners in place—and, above all, the right principals and instincts—a President Sanders could be just the foreign policy president we need.

Korb makes a powerful argument, and Mann counters what’s probably the most legitimate concern. Other than that, most of what’s been said about Sanders on foreign policy has to be taken with a huge grain of salt: It’s primarily coming from people who’ve mostly been wrong about the most important decisions of the century. People who don’t know enough about Henry Kissinger to see him as a terrible liability. Listening to them, and letting them set the agenda for how we think about the election—now that would be yet another very serious foreign policy mistake.