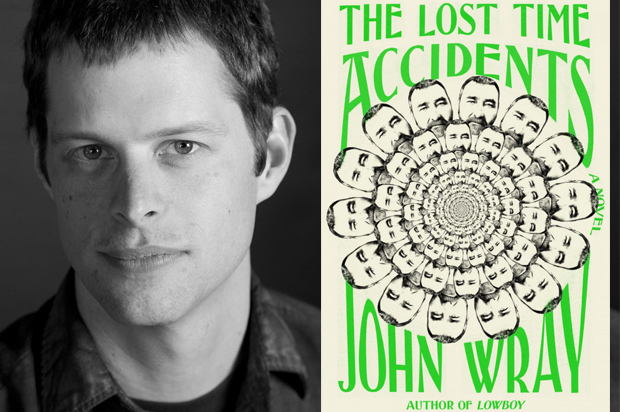

A new novel from John Wray is an event, and I opened “The Lost Time Accidents” with great excitement. I was not disappointed. Wray is something of a daredevil in the field of contemporary fiction: Each new project represents a radical break with his previous work, and the risks he takes are part of the thrill of reading him. I expected this latest novel to be an entirely different animal from “Lowboy,” Wray’s breakout 2009 success—and in this I was entirely correct.

“The Lost Time Accidents,” which Wray devoted seven years to writing, chronicles a century in the life of the Tollivers, a once-illustrious family that has fallen into elegant ruin as a result of its fascination with the nature of time. Time’s mystery seizes each member of the family differently—some become physicists, some embrace science fiction, some commit bizarre and spectacular crimes—but all of them are defined by their obsession, for good or for ill. “Time,” says our narrator and hero, Waldy Tolliver, “is our family curse,” and the novel chronicles this hundred-year jinx, in all its symbolic richness, with a masterful lightness and charm. “Time is everyone’s curse,” Waldy’s lover, the mysterious Mrs. Haven, replies. And the story that follows makes this magically clear.

I sat down with John Wray at Shopsin’s in New York’s Essex Street Market, a curious restaurant with draconian rules of conduct and an inexplicably enormous menu filled with enigmatic dishes (Bombay Turkey Cloud Sandwich, Slutty Cakes) that would have fit rather well into “The Lost Time Accidents‘” wild, eccentric world.

You spent seven years writing “The Lost Time Accidents,” while I spent 12 on my most recent novel, “Family Life.” Why the rush?

(Laughing) I actually thought this was going to be a quick book to write, since its tone is more playful that my earlier work. But it turns out that writing a comic novel—a good one, one that manages to be funny and serious both, sometimes in the same passage—is a hell of a lot harder than it looks like at first glance. We tend to take humor for granted, somehow, or to think of it as frivolous. It’s not.

No one would mistake this novel for something frivolous, certainly—it touches on a number of the greatest crimes of the 20th century, from the death camps of the Nazis to the atomic bomb, and chronicles, among a profusion of other topics, a tragic love affair.

My books always seem to tend toward dark subjects, no matter how hard I try to steer them toward the light. That sounds awfully pretentious, doesn’t it? (Laughter) But I found very quickly that you can’t succeed in packing a book with as much life as possible, as I tried to do here, and keep tragedy and horror out. I think you need a measure of bleakness, if only to frame the all-too-fleeting moments of joy. A quote by Jean-Luc Godard, of all people, has stuck with me over the years: “Periods of happiness are history’s blank pages.” I hope I’m not misquoting him too badly.

There’s a strong science fiction element in this novel, which greatly adds to the comedy, but do you consider this a work of science fiction?

One of the pleasures of a book this big is that it can be many things in the course of its trajectory, without being defined by any of them. There’s a science fiction novel hidden inside “The Lost Time Accidents” somewhere, and an end-of-the-20th-century romance, and a comedy of errors, and a seedy Third Reich thriller. It’s a literary novel that ate a pulp paperback. This aspect made it hugely fun to write. How are you liking your Slutty Cakes, by the way?

I’m … liking them. They’re interesting.

It’s the molten peanut butter in the middle that gives them their unique appeal.

Let’s get back to the book. Over the course of the narrative, its characters encounter quite a range of historical figures: Klimt, Einstein, Himmler, the Black Panthers and Joan Didion, to name only a few. Why did you do this?

Writing a novel of this length is often disheartening, as I’m sure you know—and without a commitment from the start to have as much fun with the project as possible, I’m not at all sure that I’d have made it. It’s incredibly fun to weave historical and cultural figures into a fictional narrative for some reason. Along with the samples of Orson Tolliver’s (terrible!) science fiction, the ersatz personal essay by Joan Didion that I gave myself permission to attempt near the close of the book gave me as much pleasure as anything I’ve ever written. Also, as a holder of an Austrian passport myself, I have to admit that it gave me a kind of transgressive thrill to skewer our national icon, Gustav Klimt, just a little. Not to mention giving Himmler “the eyes of cave-dwelling prawn.” (laughter)

Let’s talk a little about the elusive Mrs. Haven, the novel’s great lost love. Is it saying too much to reveal that your narrator is writing to her throughout this novel—that the book is, in a sense, an extended love letter to a single person?

Ah, Mrs. Haven—light of my life, fire of my loins! Bits of personal and family history notwithstanding, it’s in her character that I see myself most clearly, if only because I gave myself full and complete permission, in my mad scientist lab, to attempt to breathe life into my romantic ideal. For better or worse—by which I mean, ethical lapses and all—Mrs. Haven is a version of my dream lover, and her ghostly presence kept both my humble narrator and yours truly scribbling away over all these years. As Nabokov says in more than one preface to his own work, the disciples of Herr Freud should have a field day.

One of the stories running through “The Lost Time Accidents” is the resentment of mainstream science that gets passed down the Tolliver line. As family legend would have it, if Einstein hadn’t stolen the spotlight with his theory of relativity, Waldy’s forefathers’ own theories of time and space would have garnered the acclaim and attention that Einstein received. (I love, by the way, that Einstein is never referred to by name—he is contemptuously known as “the Patent Clerk” throughout.) Were there particular historical cases of scientific rivalry that got you thinking about this aspect of your novel?

There were, actually. I’ve always been intrigued by the story of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, the famous French zoologist and theorist, whose contributions to our understanding of the natural world, which were immense, were completely overshadowed by Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Lamarck got so much right, but now, if we learn about him at all, his errors are what we hear about: his notion—now partially vindicated—that the traits an animal acquires in its lifetime can be passed on to its offspring. Science is a tremendously creative field of human endeavor, of course, and when I began doing my own research for “The Lost Time Accidents,” I had the idea to consider science as one might consider literature: a rich field of parallel narratives, competing but not mutually exclusive, each of which might display its own very subjective type of elegance and beauty.

One last question. Why is there so much sex in the novel?

Is this a serious question?

Absolutely. Does it embarrass you?

I’d have to be pretty inhibited if the mention of sex in my own book embarrassed me! I wasn’t necessarily aware of writing especially many sex scenes—but what did occur to me, as I wrote, was that most of the sex in the book is good sex. By and large, the characters in “The Lost Time Accidents” enjoy the sex they have, and aren’t shy about talking and thinking about it—celebrating it, even. That’s a pretty big departure from my earlier books. In “Lowboy,” for example, the protagonist is convinced that he can change the world by losing his virginity, but the act is more a duty to him than something he seems to desire. He’s insane, of course, but so are any number of the characters in “The Lost Time Accidents”—just not in a way that interferes with their enjoyment of the world. There’s too much bad sex in the world as it is, after all. Why condemn my characters to the same unhappy fate?

Akhil Sharma is the author of “An Obedient Father” and “Family Life.” He teaches at Rutgers University – Newark. “Cosmopolitan,” his collection of short stories, will be published in 2017.