Terrorism is a form of communication. Through public spectacles of violence, it attempts to convey a message from relatively powerless groups — usually nonstate actors — to more powerful groups — usually states.

Without a doubt, the Islamic State has mastered the art of this form of communication. They’ve beheaded and burned alive captives, thrown homosexuals off the top of buildings, stoned women for being raped, and produced an online magazine that uses stunning high-quality images to convey their propaganda message. The Islamic State has also embraced an apocalyptic narrative that makes it highly attractive to young men looking for adventure and a sense of meaning in life. In fact, their recruitment campaign has been extremely successful, with tens of thousands of foreigners flocking to Iraq and Syria from all around the world.

For such recruits, what could be more exciting than fighting the infidels at the very terminus of world history? What could be more thrilling than clearing the way for Jesus to descend over the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus before he hunts down the Antichrist and slaughters him in the modern-day town of Lod, in Israel? (This is what the Islamic State actually believes.)

In the pursuit of fulfilling what it believes is God’s wish for humanity, the Islamic State has openly fantasized about acquiring a nuclear weapon from Pakistan (which has a history of leaking nuclear secrets), shipping it across the Atlantic, smuggling it through the “porous borders” of South America, and detonating it in a U.S. city. It’s also pondered the possibility of weaponizing the bubonic plague, and even trying to spread Ebola by infecting some of its own members and them putting them on an airplane. While the Islamic State’s initial aim was provincial — to build a caliphate in Iraq and Syria — it later expanded its ambitions with coordinated attacks outside its territories, such as in Paris on Nov. 13, 2015. And there’s evidence that an attack on the American homeland may be one of the Islamic State’s resolutions for the new year. As Vincent Stewart, who directs the Defense Intelligence Agency, testified on Capitol Hill earlier this month, the Islamic State “will probably attempt to conduct additional attacks in Europe, and attempt to direct attacks on the U.S. homeland in 2016.”

So the threat is real and ongoing. As President Obama correctly noted back in 2009, even a single nuclear device exploding somewhere on Earth “would badly destabilize our security, our economies, and our very way of life.” An exactly similar thing could be said about a bioterrorism attack, which the former secretary-general of the U.N. Kofi Annan describes as “the most important, under-addressed threat relating to terrorism.” The stakes are high today — in fact, higher than they’ve been in the past.

But the Islamic State probably isn’t the greatest long-term threat to the Middle East — or to the West. While it’s managed to gain a monopoly of media attention because of its theatrical exhibitionism, many experts believe that there are even more dangerous nonstate actors lurking in the shadows. For example, former director of the CIA David Petraeus has claimed that Shia militia in Iraq threaten the “long-term stability and the broader regional equilibrium” of the Middle East more than the Islamic State.

An early militia of this sort was the Mahdi Army. It was formed by the influential Iraqi leader Muqtada al-Sadr for the express purpose of driving out the invading Western forces, and its religious ideology had an important apocalyptic twist to it. As the Islamic scholar David Cook writes, the Mahdi Army probably believed that “the purpose of the US-led invasion was to initiate an apocalyptic war — in this case, to find the Mahdi and to kill him.” The Mahdi is the end-of-days messianic figure of both Sunni and Shia Islam, although his role in each tradition is considerably different.

While this may sound like a pedantic detail of the Mahdi Army’s worldview, I’d argue, quite vigorously, that those of us in the West simply can’t understand what’s going on in the Middle East today without some sense of the eschatological beliefs that animate so many Sunnis and Shi’ites in the region.

The Mahdi Army actively fought the Coalition forces for more than half a decade, but in 2008 it spawned, and was replaced by, another Shia militia revealingly named the Promised Day Brigade. This group has since emerged as “one of the most prominent … Shiite militias operating primarily in and around Sadr City and Baghdad,” which the Islamic State failed to capture because of Shia militia resistance. (Sadr City is a suburb of Baghdad.) The Promised Day Brigade is also known to “receive training, funding and direction from Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force,” an elite special forces unit that the U.S. has classified as a terrorist organization since 2007. The fact that the Promised Day Brigade is actively supported by Iran — one of the major regional powers — is why Petraeus has worried that, “Longer term, Iranian-backed Shia militia could emerge as the preeminent power in [Iraq], one that is outside the control of the government and instead answerable to Tehran.”

But Shia militias aren’t the only nonstate threat more significant than the Islamic State. A recent report by the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute argues that the Syrian-based terrorist group Jabhat al-Nusra (or the al-Nusra Front) is “much more dangerous to the US than the ISIS model in the long run.” Al-Nusra is an affiliate of al-Qaida, and it played a central (albeit somewhat incidental) role in the emergence of the Islamic State.

Briefly, the story is worth recounting for the sake of context: the Islamic State itself began as an al-Qaida affiliate called “al-Qaeda in Iraq” (AQI), led by an apocalyptic psychopath named Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. After al-Zarqawi’s death in 2006, the new AQI leadership decided to declared an Islamic state in Iraq to “fill security vacuums” left behind when U.S. troops withdraw from the region. Consequently, AQI changed its name to the “Islamic State of Iraq” (ISI). Then, in 2013, the head of ISI, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, abruptly announced that al-Nusra in Syria was now under his control, thereby yielding the “Islamic State of Iraq and Syria” (ISIS). The problem with this merger is that neither al-Nusra nor al-Qaida approved of it. This resulted in a political dispute that (along with disagreements about ISIS’s brutal tactics) led to ISIS becoming an independent entity. A year later, ISIS made an even bolder declaration that it was establishing a caliphate called the “Islamic State,” whose aim is to usher in the final events before the Last Hour.

The point is that the Islamic State’s claim to legitimacy is crucially dependent upon the continued existence of its caliphate, which some believe will eventually “cover the entire Earth.” Consequently, as Graeme Wood points out, if the Islamic State “loses its grip on its territory in Syria and Iraq, it will cease to be a caliphate. Caliphates cannot exist as underground movements, because territorial authority is a requirement: take away its command of territory, and all those oaths of allegiance are no longer binding.”

In contrast, al-Qaida and its affiliates, like Jabhat al-Nusra, “can survive, cockroach-like, by going underground.” Such groups are defined not by territory, but by ideology, and this makes them especially difficult to target and destroy. In fact, as the president of the Institute for the Study of War Kim Kagan observes, “Al-Nusra is quietly intertwining itself with the Syrian population and Syrian opposition. … They are waiting in the wings to pick up the mantle of global jihad once ISIS falls.” And ISIS will eventually fall, given its flawed “caliphate-now” approach. The result will be new opportunities for al-Nusra to strike Western targets, a goal that the group has, Kagan says, made a “tactical decision” not to pursue right now.

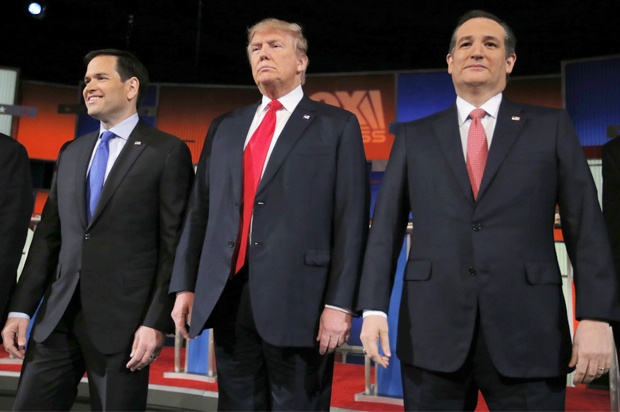

While foreign policy discussions in the media and during presidential debates has largely focused on the Islamic State, this could be a mistake. By many accounts, al-Baghdadi and his army of religious extremists hoping to bring about the apocalypse could be the least of our worries — in the long run. However difficult it may be to widen our perspective and avoid the seduction of myopic strategies, it’s crucial that we recognize the real threats to our country. Some terrorists “don’t want a seat at the table, they want to destroy the table and everyone sitting at it,” as the former director of the CIA James Woolsey puts it. Recognizing which terrorists are most likely to actually accomplish this is our only hope for long-term success.