Sometimes, when my mother was very tired, her words would fail her and she would sign to me and my sisters instead. Usually she only ever got as far as signing “stop”—open palm, one hand coming down on the other, easy enough to translate. “You’re doing it again!” one of us would shriek, and she would catch herself and sigh, exasperated, “Girls.”

Like all the women in my family, my mother loves language—gusts of words and coaxings and questions, always questions. She is almost never at a loss for words, but when my sisters and I were younger we did our best to overwhelm her, to see what it took to get her words to go and her signing to take over.

Our mother learned to sign because she is, above all, a curious person. It is a trait that’s led her many places in her life. To a deaf university, Gallaudet, for graduate school. To the backwoods of 1970s Maryland to work with the developmentally disabled children warehoused in the state’s asylums, about to be released into a world that wasn’t ready for them. But my favorite story of where her curiosity took her—well, almost took her—was to a research institution in upstate New York, to live with a chimp and raise it. This was before I was born, when she was a newlywed. She was living in Brooklyn and taking advanced signing classes at Hunter College. She interviewed for the job, and they wanted her right away when they found out one of her daughters was 2 years old. To my sisters’ and father’s eternal disappointment, my mother said no. “I realized I’d have to raise that animal as my own. And then leave it behind, when we would move—it was too cruel,” she’d explain. My father grumbled about the loss of a good deal—the mysterious institution, never named in her recollections, would have given them a house in Westchester County, rent free, and a car. My older sisters lamented a lost playmate.

I thought about that story for many years, and then I decided I wanted to write about it. I did some research and found that raising a chimp alongside one’s child is actually a surprisingly common occurrence. There are numerous memoirs about the strangeness of sharing space with an animal, the loneliness of difference, the sadness of losing one’s sibling.

Even as I read those memoirs and became interested in writing about that story, I knew that I wanted the novel to be about something more than just that experience.

For nearly 10 years I worked as a tour guide at African-American historic sites. All day, every day, I either talked to people about race and history, or thought of new ways to disseminate historical research to the general public. I talked to grade-schoolers and high school students and militants and scholars; sometimes to people who cared deeply about black history and sometimes to people who had absolutely no interest in it or sometimes to people who were openly hostile toward it.

It became evident that there was something wrong with how Americans attempted to talk about race. There was a given narrative that most people, or people who counted themselves as decent people, generally followed. This narrative was known by black people and non-black people. It was obsessed with progress. It was uplifting. It did not allow for tangents or for misfits or for bitterness. Then there were those deeply invested in a version of black history that only cared about the pain, the degradation, the terror. This faction rejected any attempt to explore a position other than the defensive, arguing that any experience less than constant trauma was not authentic enough. And then, of course, there were those who wished so badly for American ideals—liberty and justice for all—to be true, that they refused to acknowledge any atrocities at all.

It became clear that language was failing me, was failing all of us. And our stories about the past were failing us as well. The stories and the language that we used were obscuring what needed to be said.

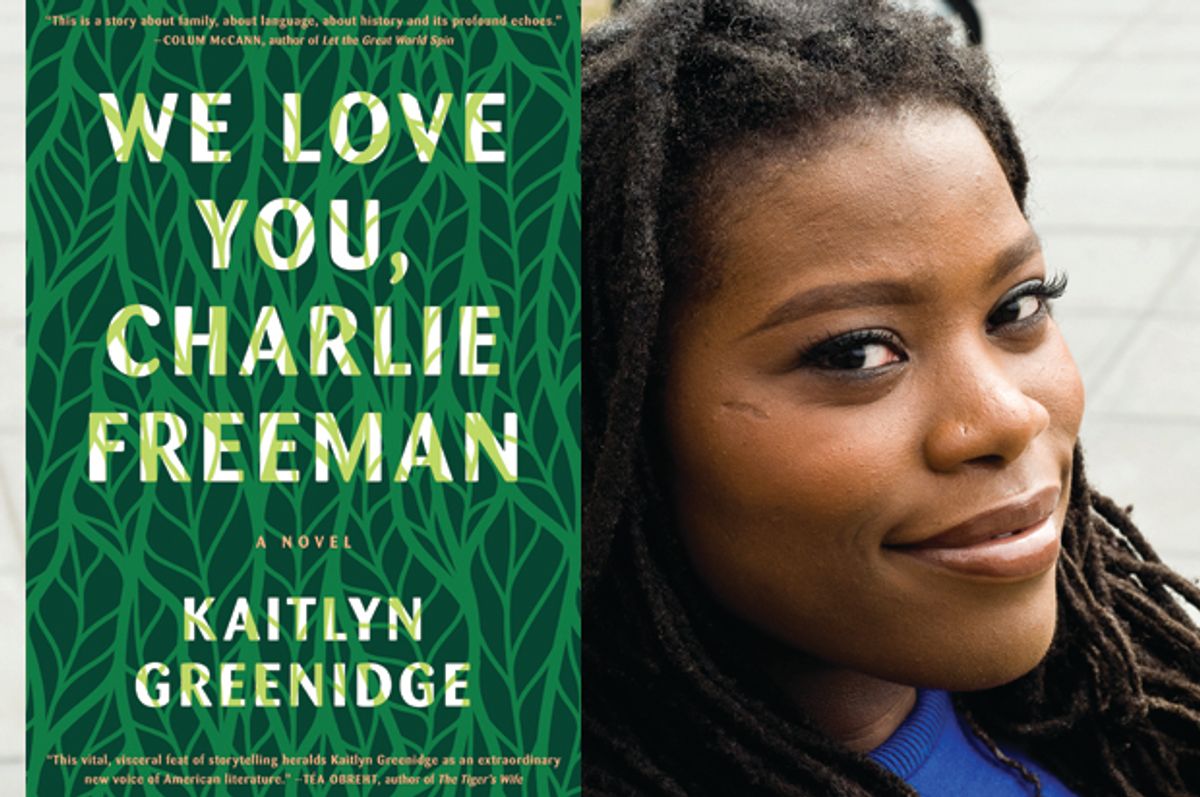

I decided to use the story of a pretend experiment (similar to the job my mother was offered decades ago) to talk about the intricacies of race and memory and history. "We Love You, Charlie Freeman" is about a black family who moves to a nearly all-white town in Western Massachusetts to teach sign language to a chimpanzee named Charlie. The Freemans are chosen to take part in the experiment because of their race, and the citizens of the town they move to and the research institute sponsoring the experiment are chronically stymied, unable to address or even acknowledge transgressions of the past and present.

Interwoven with the story of this family is the story of Nymphadora, a black woman in the 1920s, whose connection to the research institute involves a crime that is linked to its founding. The decision to include Nymphadora came about because I’ve been fascinated by the American Eugenics movement since I was in college—a book I came back to, again and again while writing this novel, was "The Mismeasure of Man," Stephen Jay Gould’s exploration of scientific racism in 19th and 20th century American academia. What that book provided, and what I tried to bring into this novel, was other stories about race, other narratives besides the pat ones I’d encountered as a historical interpreter, about what it means to be a white or a black or a raced person in the United States.

This book is an attempt to join in the conversation that the United States has had since its founding, our never-ending story and cry and argument about race. It’s an attempt to make peace with the language we have now, in this moment—broken, and inadequate, and wondrous, all at once.

Shares