About this time every year I realize that the Sept. 11 attacks changed my life, and the lives of millions of other Americans.

For the better.

There. I admitted it. Strange to say the words so baldly, but the truth is the truth.

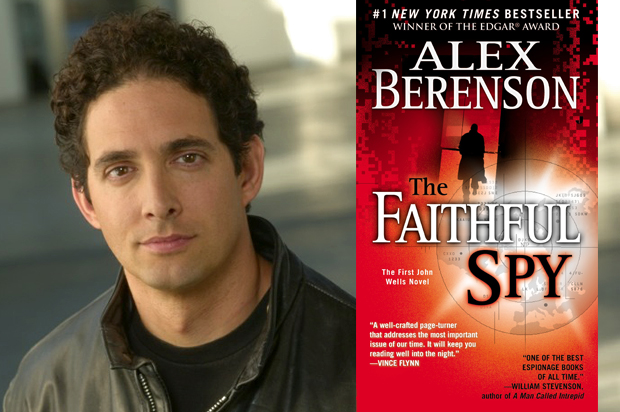

Four years after the attacks, I wrote a novel called “The Faithful Spy,” about a CIA officer who had infiltrated al-Qaida but couldn’t stop them. It became a best-seller. I’ve now written 10, all focused on espionage and terrorism. They come out each February.

I never know what to feel about this devil’s bargain. I didn’t choose it, but I didn’t walk away either. And though the story sounds like an outlier, whenever I visit Washington, as I did last week to promote my new book, I am reminded that it isn’t – and of its real cost.

The national capital is filled with people who have prospered thanks to Sept. 11, whether they admit that reality to themselves or not. They are coders at the National Security Agency, case officers at the Central Intelligence Agency, war planners in the Pentagon, satellite engineers at the National Reconnaissance Office, and the endless dragoons of consultants at Boeing and a thousand other companies. They do their jobs in heavily guarded office campuses with names like Liberty Crossing. They work hard and mean well, mostly.

And I’ve grown convinced they are a large part of the reason that ordinary Americans feel so alienated from the government that is supposed to be theirs.

Almost 1 million people now have top-secret level security clearances. More than 3,000 companies and agencies work on counterterror, homeland security and intelligence programs. But despite Edward Snowden and other leakers, we know little about what all those people actually do, how much money they make, or what liberties they take with ours. The veil of secrecy is too thick, the criminal penalties for talking too severe.

Meanwhile, the people who run the agencies – and the politicians who oversee them – still will not discuss in plain English whom they target, how they keep themselves from making mistakes, and what happens if they do. To say nothing of the broad outlines of their capabilities, or the size of their budgets and their workforces. No one needs to know exactly how many drones the United States has. But shouldn’t the government acknowledge when they strike? How long can we fight this war, and how many people can we kill, without admitting what we’ve done?

At the same time, the perpetual secret war is corroding the relationship between government and governed. The symbolism of the perpetually expanding security core around the White House can’t be ignored. Downtown Washington reminds me more of central Moscow every time I see it. The monuments and memorials are pleasant distractions for tourists. But the buildings where the real work is done might as well have force fields around them.

I am old enough to remember walking through the White House with my parents. We didn’t donate a million dollars. We got in line, walked through a metal detector, and saw the public spaces in what actually seemed to be the people’s house. That term seems worse than ironic now, with Secret Service officers in black uniforms and Kevlar vests keeping anyone even from reaching the sidewalk on Pennsylvania Avenue.

Somewhere the Secret Service has calculated the lethal radius of a 10-kiloton nuclear bomb, figured the odds that terrorists could smuggle in nerve gas components. Those fears are real. But the pendulum has swung much too far in the direction of secrecy and self-preservation. It feels sometimes as though the federal security apparatus, from top to bottom, exists mainly to protect itself and to provide jobs for its members. Even asking the right questions is next to impossible when all the relevant facts are classified.

A government that keeps so many secrets is hard to trust, easy to fear. And in this meanest of political seasons, the fear many ordinary Americans feel is palpable.

The attacks happened. We can’t go back. I wouldn’t unwrite my books, even if I could. But all of us – especially the people in the secret world who owe their careers or fortunes to Sept. 11 – need to find a way forward. Before our security strangles us.

Alex Berenson, a former reporter for the New York Times, writes the John Wells series of spy novels. Putnam published the most recent, “The Wolves,” earlier this month.