Ever since he burst onto the literary scene almost 25 years ago, writer Chris Offutt has been offering lyrical and insightful looks into the lives of working people. His latest book gives us a peek into a world of work few of us might ever see: pornography literature at the height of its heydey in the ’60s and ’70s. Even better, the man at work here is Offutt’s father, Andrew Offutt, who wrote about 400 porn novels over the course of six decades. Andrew Offutt also wrote science fiction, fantasy novels and thrillers.

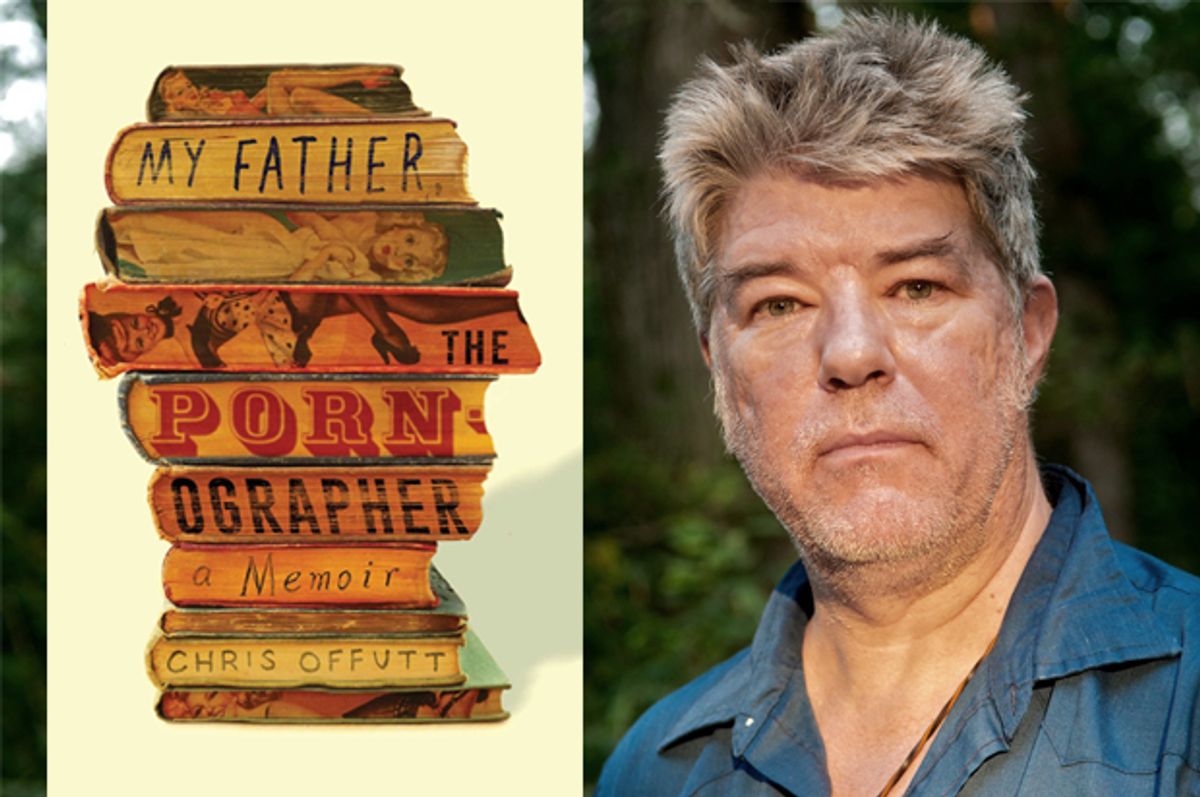

The memoir that recounts this working man’s epic output is “My Father, the Pornographer,” and it is already being hailed by the likes of author Michael Chabon as a masterpiece. In a glowing review, the New York Times called it “unexpectedly moving”; the Washington Post says it is “touching” and “haunting,” while a reviewer at the Boston Globe proclaims it “One of the most sensitive, nuanced examinations of father and son relationships I’ve read.”

“My Father, the Pornographer” is much more than a look at a man who is regarded as one of the most prolific writers of pornography. In the book, the pornographer’s son carefully goes through his father’s astonishing legacy: more than 1,800 pounds of writing. Meanwhile, he also recounts his childhood with a man whom he found terrifying. “My father was a brilliant man, a true iconoclast,” Offutt writes, “fiercely self-reliant, a dark genius, cruel, selfish, and eternally optimistic.” His memoir is a tender and compassionate book that takes on a specific premise while revealing the universal complexities of child-parent relationships and the struggle of having family members whom we must accept can never love us properly.

Chris Offutt is at the top of his game with "My Father, the Pornographer," delivering on the acclaim he received in 1992 with his debut, the widely read short story collection “Kentucky Straight.” Since then he’s published a novel, “The Good Brother” (1997), another story collection, “Out of the Woods” (1999), and two other memoirs: “The Same River Twice” (1993) and “No Heroes” (2002), as well as a host of writing in some of the country’s best magazines and anthologies. Over the last few years he has turned to television writing and has written episodes for shows such as “True Blood” and “Weeds.”

Offutt recently sat down with Salon contributor Silas House for a conversation that is compelling and deeply moving, just like his remarkable new book itself.

Early on in the book you recount a moment when your father tells you that he didn’t know he’d given you a childhood “terrible enough to make you a writer.” The rest of the book recounts the fear, dread and loneliness you experienced as a child. Did what he defined as a “terrible childhood” make you the writer you became?

No. Dad's comment was more about his view of his own childhood than mine. He had a Freudian view of psychology: if this, then that. He believed he was unhappy as a child and that in turn made him a writer. When I got in print he assumed the same about me.

I included that anecdote because it was such a surprising response. I'd wanted something else from him--approval or pride--but he made my book about him. Both about his childhood and his own perceived failure as a father. It was one of the two times he'd admitted his own culpability to anything.

Do you believe that artists—whether they be writers, or actors, or whatever—need to have experienced real trouble in their lives to excel at their art, or is that just a stereotype?

I believe anyone can do anything they want. There's no recipe for being a writer, actor, composer, or painter. And there's certainly no prerequisites. You just have to want it bad enough, and be willing to make very real sacrifices to get it. Most career criminals have experienced real trouble. Does that make them better crooks? Many of our politicians come from a background of privilege, but turn out to be terrible at their job.

There exists a glamorized view of hardship and artistic achievement. Young people who believe this can easily become self-destructive in their desire to "suffer for their art.” They think they need hardship. But we all have hardship in our own way. Genuine suffering can lead to wisdom. It can also lead to despair and cruelty, drug addiction and violence. Artists are people who manage to take all this and turn it into something new. They make something. All artists excel for the same reasons: they are disciplined, diligent, and possess endurance. In order to develop artistic skill, you must have time to do so. Due to circumstances, some people simply don't have the time and energy. Others who do, squander it.

While the book’s title explicitly points to this being your father’s story, your mother is just as powerful a character throughout the memoir, and passages about her are often very revealing and sometimes difficult truths. Since she is still living, did these passages lead to uncomfortable moments with her?

Not really. Mom was much more reticent about Dad when he was alive. After he died, we had very frank and open conversations. She typed all of Dad's final manuscripts for submission to the publisher. She also knew that she'd asked a lot of me as a child--to take care of my younger siblings while she typed and took care of Dad.

Mom was my primary source, other than Dad's massive archive. I consulted her regularly on my progress. She read the book in galley form before publication. I was concerned about her response, fearful that she might not like it. What she said surprised me: "It made me miss Andy."

Do you think she was held back in what all she could have accomplished by being deeply in love with this all-encompassing man who was your father?

No, I don't think so. Mom believed being married to Dad enhanced her life. She had four kids and didn't have to work outside the home. She went to college in her forties and fifties, taught college and worked for a lawyer. Due to Dad's work, Mom traveled to SF (science-fiction) conventions and had friendships with diverse people.

Mom is not a particularly ambitious person. She was born in the Depression and came of the age in the 1950s. She was a product of the conventions of the era--she wanted to be a good housewife and mother. She did her best. At the same time, I've never seen her happier than the past few years.

So do you chalk that new kind of happiness up to a new kind of freedom for her, or just a new phase in her life? Not a feeling of being released from him?

I think it's a combination of things. She'd never lived alone and is still excited about that. She lived with her father until she got married, then with her husband until he died. Her own mother died very young, and Mom took care of her sister and father. Then she took care of her children and husband. At 78 she was released from the responsibility of having to look after others.

Dad's secret life as a pornographer meant she had to keep that secret as well. I grew up in Rowan County, which was in the news last year because the county court clerk refused to issue marriage licenses to gay couples. I know the clerk [Kim Davis] and knew her mother. They knew my parents. This level of conservative thought was part of the reason Mom and Dad kept their porn enterprise secret.

Leaving that area released her from the pressure of maintaining secrecy. The first thing she noticed when she moved to Oxford, Mississippi, was that she could order a glass of wine at lunch in a restaurant and nobody thought anything of it. She and I are probably the only people in America who moved to Mississippi for the more progressive politics!

Your relationship with your mother comes through beautifully in the book. In many ways the memoir is largely about the relationships between parents and children. So there are many universal scenes throughout the book. In one powerful scene where you write on the wall of your parents’ home as an adult in your fifties, you think “If Dad found out, he wouldn’t like it, and I’d get in trouble.” Do we ever get over trying to please our parents?

In my case, it was nearly impossible to please my father. Trying to avoid making him mad was always a bigger priority. This was due to fear. I'm not convinced that fear is a good motivation for trying to please anyone--parents, children, partner, friend, or neighbor. If you're afraid of someone, you can appease but rarely please.

When I wrote instructions on the basement wall for the plumber, I experienced a very childlike element of sheer defiance. Embarrassing to admit. Perhaps on some level I knew that Dad would never know. He couldn't get down the steps.

But that anxiousness is well earned. I mean, your father does some pretty unforgivable things—chief among them is the fact that he took the money from a college fund your aunt and grandmother had set up for you and your siblings and used it for himself. He sold your comic book collection. He cashed your brother’s college financial-aid check. Yet you still went to him when he was sick, and you paid his literary archives the respect of delving into them when others might have just lit a match. Is the fact that you and your siblings even managed to keep speaking to him a testament to the powerful bond between child and parent?

I went to see him because my mother called and asked me to come home. Dad was hospitalized and she wasn't sure why. She called me because I'm the oldest and she'd always relied on me. I helped her deal with doctors and the hospital, and arranged for a wheelchair ramp to be built at home.

Dad was extremely dramatic and prone to grandiosity. After his own mother died, he sent me a "Secret Will" that put me in charge of his literary archive. I took on that task because none of my siblings wanted to. They wanted to destroy it and my mother didn't care one way or another.

So with that in mind, do you think you took on the task and were more curious about it than your siblings mostly because you’re a writer? And is that probably why he wanted you to be the one who did it? Or was there another reason at play?

Dad wasn't close to any of us, but he talked to me about his work more than he did to them. I believe he feared their judgment. I was more curious about Dad and his work than they were. We all knew that. Dad made no arrangements for his archive. He just put me in charge. It was an odd form of posthumous trust.

Going through it was a way to learn about my father that he never allowed while he was alive. As a writer, I believed that Dad deserved a bibliography. The book evolved from my efforts to assemble it. After finishing the book, I moved all 1,800 pounds to a storage unit. I had no interest in keeping the material in my house.

Would there have been some satisfaction in putting a match to the literary archives? In destroying them instead of preserving them?

Yes, absolutely. It would have saved me a lot of stress and let me finish the novel I set aside to deal with his death. But it would have been a grand gesture, one I'd have probably come to regret. Plus, it would have taken a long time. Stacks of paper don't burn readily. I'd have to dig a hole and douse it all with kerosene and hope the wind didn't kick up.

There is a common thought that a streak of meanness or antisocial behavior is even more rampant amongst geniuses. You describe your father as both a genius and as cruel. Are those two things related, or do we just excuse the cruelty of geniuses more because of their genius?

No, I don't think being cruel and a genius are related. There are many kinds of genius: physical, visual, literary, scientific, etc. Most writers are social misfits as children. The world of literature provides a healthy escape and the next step is to create those worlds oneself. The occupation requires years of time spent alone in a room, which can erode social skills. It is necessarily a selfish occupation. Conversely, you have to turn away from the world to write about it.

Cruelty is not a side effect of being a genius, or of artistic achievement. It is often an expression of poor self-esteem and inner pain. People lash out because they are scared or hurt. I think it was both for my father. Some part of him also enjoyed being cruel. I don't know why.

Dad often referred to himself as the happiest man in the world. I don't think that was true. He spent 15 years as a salesman, and I believe he became adept at selling himself on whatever he needed to believe at the time.

This book is also about grief, although most of the media around it has centered more on the sensational aspects of your father being a pornographer, while overlooking this fact.

In one way, I lost my father many years ago. I understood that he was damaged somehow, that he couldn't change or improve, would not visit his children. I was able to accept that I'd never have the father I wished I'd had. That was a more profound grief than his death.

Would you say, then, that you’ve had a long bout of grief since accepting that you’d never have the father you wanted? That, in some way, you’ve had a grief-haunted life because of that realization?

Most people don't have the parents they might have preferred. And some parents don't get the kids they prefer, either. For both parties, the best route is acceptance, not grief.

Like you, I grew up in the hills of Appalachia. It is a hard world, with high unemployment, poor education and lack of opportunity. That results in dire social problems. By the time I was 30 I knew about 25 people my age who'd died. That's not the case in all environments. If I'm grief-haunted, it's because I can't comfortably live in the most beautiful part of the world.

So which allowed you to work through the grief of losing your father better: dealing with his eighteen hundred pounds of written legacy or writing your own book about that process?

Dealing with his archive and writing the book are inseparable. I didn't intend to write a book, but put together a bibliography. None of his material was organized. To keep track, I started taking notes about his work. Then I took notes about the notes, and added comments. It was like a private form of Midrash. Pretty soon those notes evolved to narrative. By the time I completed his bibliography, I had a 400-page manuscript. I then cut 150 pages and tried to make a coherent story.

His death meant he could no longer hurt me. That in turn supplied a compassion and generosity toward him that ultimately benefitted the book.

So the book allowed you to look at your relationship to him with more complexity than you had before?

No, not the book so much as the archive itself. Dad saved everything he wrote going back 60 years. Most adult children don't have the degree of unfiltered access to a parent that I had. He didn't save it for me, he just kept it all.

Going through it and writing the book didn't change our relationship, or our history. But it gave me a great deal of insight into my father, which in turn provided some about myself.

Throughout the memoir, you find comfort in nature. At one point you tell us that you have even recorded the birdsong of your native hills to comfort you in hard times. A couple of times you realize that the family members you are most devoted to are the hills you grew up with. What is there in the woods that offers a balm to you?

Beauty and peace. Tranquility and calmness. There is nothing prettier than light in the woods, wildflowers, the sound of a creek and birds. I feel safe in the woods, safer when I'm alone. Some people find that solace in church, others by listening to music, or reading quietly by a fireplace. For me it's always been nature.

Yesterday I took a long walk in the woods behind my house. I've been there dozens of times, but each time I see something new. Nature is brutal and relentless, but it is also gorgeous and balanced. I came home dirty, wet and happy. I've learned more from being alone in the woods than anything else. I can't fully explain it.

One thing that is so interesting—and universal—about this book is the way that even while we are striving to not become like our parents, we unconsciously do. Can you talk about that a bit?

Because I was the oldest, I didn't have an older brother or sister to emulate, and we didn't live near any family. As a boy, I naturally copied my father. His opinions were always strident, extreme and self-righteous. Not much nuance. He was a strong thinker, but mainly an either/or thinker.

During my teenage years, I began to rebel. I didn't want to be anything like my father and rejected many of his values. This let me form my own opinions and values. I believe all this is typical of many people. When I had sons, I was determined not to raise them the way my father had raised me. At the same time, I often felt the impulse to respond to them the same way Dad did to me. I tried to resist it. The result is that I'm very close with my sons.

Writing this book required a deep examination of my father's mind. I had to "enter" his way of thinking at times. And yes, we are much alike. Same occupation of writer. A similar preference toward solitude. For nearly three years I worked 10 to 12 hours a day to the exclusion of most else. That's how Dad worked, and now I was doing the same on a book about him. Dad was obsessed with sex and porn. At a certain point I realized that I was obsessed with Dad's obsession with sex and porn. It was a strange moment and I didn't like it much. At the same time, we are also very different. My wife and sons consistently pointed this out. I needed to hear it.

Another parallel between the two of you is that your father started writing porn to support his children and you turned to writing for Hollywood to put your sons through college. Which is the darkest territory to enter: the porn scene of the ’60s and ’70s inhabited by your father, or modern Hollywood?

The porn market exploded in the 1970s. Consumer demand had never been higher. Publishers needed content, which meant they needed writers. Dad exploited that demand for money. In the 2000s the television market exploded in a similar fashion. Today there are more networks and means of distribution than ever before. Consumer demand has never been higher. And there is an incredible need for content and writers. I exploited that demand for money.

Neither territory is dark, per se. It's how people react to it. My first response was to walk everywhere because driving in L.A. scared me. Hollywood is an intensely alluring place. It requires a collaborative effort, which I enjoyed. After years of writing alone in a room, it was nice to have people around, and most are incredibly talented. The stakes are very high--money, status, power--and that influences all decisions. Working there was intoxicating but draining. I learned a lot.

This is a memoir about pornography, but your book never becomes dirty—it’s gritty, but never gratuitous. Why did you decide to not include excerpts of his pornographic sex scenes?

I wanted the book to be about my father, and our relationship. That he wrote porn made him more unusual than most fathers. That he did it in eastern Kentucky made the story, and my childhood, equally unusual. I believed that including excerpts of his porn would bring down the overall tone, and undermine what I was trying to do. Besides, if people want to read porn, they can do it on their phones!

The most disturbing sections of the book are the ones about your father’s fantasies about torturing and demeaning women. Those passages are obviously the hardest on you, as his son, too. Have you come to terms with that writing of his?

Not really. It was the biggest and worst surprise in his archive. Reading it or looking at the comic books he created made me feel terrible--physically and emotionally. He didn't understand his own impulses, and at times expressed shame and confusion about them. But he followed them to the extreme.

It was a kind of addictive habit that fastened on him young. His work didn't evolve much, didn't progress. He got better at it, but his ideas became more extreme instead of interesting or deeper. He thought there was something wrong with him, that he couldn't help it. One thing that surprised me--I wound up with a kind of sympathy for a person, any person, who had such awful violent thoughts and imagery in his head. That it was my own father made it worse.

I’d venture to say that your father’s writing has received more mainstream media attention because of your one book about him that the more than 400 he wrote himself. How do you think he would feel about that?

I think Dad wanted people to know how prolific he'd been. I'm speculating after the fact. My mother recently told me that Dad would have loved the attention. I believe Dad judged himself very harshly and assumed everyone else did, too. He wanted to be known for his work, but didn't want anyone to know he'd done it. A very difficult spot to be in.

When he died, all his books were out of print, every writer's worst nightmare. It's been the fate of many genre writers, some undeservedly so. I think it made him sad and angry, which in turn made him more isolated. Perhaps that resentment led to the extreme violence in his later work. But to answer the question, Dad probably would like the attention but figure out a way to be angry and resentful about it, too.

How much of an emotional and physical toll did writing this book take on you?

Well, as we say in the hills, it plumb wore me out. I was exhausted in every way, and to a certain extent I am still recovering from it. To be objective about his work I had to create a distance from myself and the content. That distance crept into my life. I became distant from myself. I gained weight and started smoking again, then quit and started back six times. For a while I had absolutely no interest in sex whatsoever. It was like an overdose of porn.

I put everything into the book, which meant it took everything out of me. After finishing it, I felt relieved, a little lighter in every way, unburdened.

Shares