The two defense lawyers who represented Steven Avery, and gained overnight stardom from the Netflix docu-series “Making a Murderer,” kicked off a North American road show last week that will take them to 33 cities by the end of summer.

That’s a long way from the dusty county courthouse in Manitowoc, Wisconsin.

Appearing Friday before a hometown crowd in Milwaukee, Jerry Buting and Dean Strang were greeted with whoops and hollers as they took the stage for a 90-minute “unfiltered discussion” about the criminal justice system and the case that made them folk heroes to some, scoundrels to others, and unlikely sex symbols to still others.

The Netflix crowd, if there is such a demographic — bearded men and bespectacled women in normcore, equal parts law students, armchair detectives and aging professionals — were fans all the way. Sitting beneath the gilded ceiling of the historic Riverside Theater, they could have been at a Sufjan Stevens or Jackson Browne concert, singing along with every song. They knew the film’s back story, its players, its every twist and turn. Yet they wanted more: a second encore, a third.

Of course, that’s been the appeal of the series from the start. Despite the guilty verdicts, the convictions and life sentences of Steven Avery and his nephew-accomplice Brendan Dassey, the story has no ending. Avery and Dassey both are appealing their convictions. Filmmakers Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi reportedly are considering a sequel. And the show goes on.

With the release of all 10 episodes on Dec. 18, “Making a Murderer” leaped into the public consciousness. Dripping with drama, supercharged with controversy, and populated by true-life characters — many of them unlikable yet oddly charismatic — it went beyond water-cooler fodder. It became a national obsession.

Reaction to the series has become a virtual true-crime parlor game, with viewers taking sides and duking it out on social media: Avery, one side claims, was rightfully convicted for murdering 25-year old Teresa Halbach, then burning her body outside his mobile home near Manitowoc. Not so, counter the skeptics. He was framed by police whose calculated disregard for justice had put him behind bars before, for a crime he did not commit.

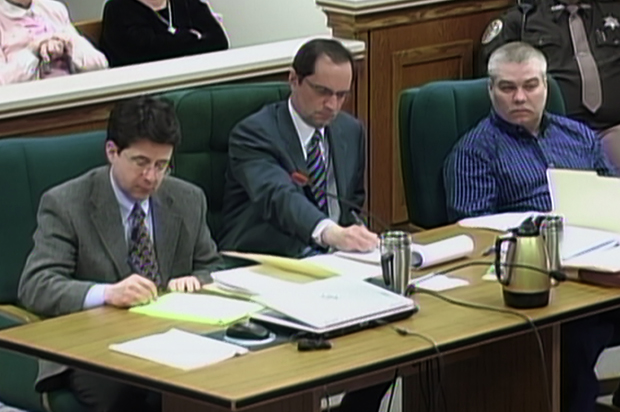

Meanwhile, cast through the filmmakers’ subjective lens as noble pursuers of truth and justice, Avery’s defense lawyers became accidental celebrities, their on-screen personae deconstructed by infatuated magazine writers and fawning fans: Buting as the combative one, a forensic wizard, attack dog when necessary, and full-on Twitter freak; Strang, the compassionate one, a former federal public defender, unpracticed in social media yet an online heartthrob, whose Tumblr image of him lounging barefoot on a couch inexplicably gave certain followers fits.

On Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and websites worldwide, every angle imaginable was explored, every conspiracy theory dissected. Rotten Tomatoes gave the doc a 97-percent rating, while celebs like Ricky Gervais and Mandy Moore and Alec Baldwin weighed in on social media.

And in no time at all, up sprang a cottage industry hawking anything tangentially related to the docuseries. “Free Steven Avery” bumper stickers flooded online markets and souvenir shops, while T-shirts extolled the sex appeal of the defense team: “Jerry Buting in the streets, Dean Strang in the sheets” and “Dean Strang is BAE.”

Podcasts popped up on Radiolab, Reddit and iHeart Radio. A software company in Palo Alto offered the StevenAvery.org Web domain for a cool $1,000. Downloads of trial transcripts – some 13,300 pages — were free for the taking, financed through a crowdsourcing campaign.

Faster than you can say “I object,” at least a dozen books showed up on Amazon, most of them e-books and nearly all of them panned. One promises multiple sequels: “Fool’s Paradise: The State vs. Steven Avery (The Halbach Murder Mystery Series Book 1).” In the Creepy Yet Creative genre, “The Steven Avery ‘Making a Murderer’ Coloring Book” invites adults and kids alike to colorize the line drawings of courtroom caricatures and crime scenes, and then post the artwork on Instagram.

And then there’s “Kill the Rich,” a paperback mystery listing Steven Avery as the author and displaying his photo on the cover. The 315-page novel cries out “hoax” and “scam.”

“I wrote this book from my prison cell,” reads the dubious bio of the author. “It was the only way I could think of raising the money for my next appeals challenge. Please be kind in your Amazon reviews. I had to write this book without access to Google or the Internet. Just me, an old manual typewriter, and some yellow note pads. Plus, it’s hard to write a book while murderers and rapists are shouting and fighting all the time.”

***

I came to the “Making a Murderer” phenomenon late. As a reporter, I had worked on a magazine article in late 2005, chasing the back roads of Manitowoc County, visiting the Avery auto salvage company, interviewing friends and family members of the victim and of the accused – looking for an explanation for the disappearance of Teresa Halbach.

After Avery’s arrest, I interviewed him by phone when he was in jail. Exonerated for a violent rape, he was behind bars again. The déjà vu twist was nearly beyond belief.

When “Making a Murderer” debuted 10 years later, it took me weeks before I finally gave in and binged. I had seen too much of the drama close-up. It was buried deep in my subconscious, and I didn’t hurry to dislodge it. I had lived it for months, dreamed it, walked on the land near the crime scene – a massive, hilly vehicle-strewn property that had come to represent a place of savage violence and suffering, a Wisconsin gethsemane.

It’s hard to reconcile the quick-buck hustles, the overkill of media coverage, and the wild popularity of two above-average criminal defense lawyers who were simply doing their jobs. This, after all, is the story of a young woman who was murdered, a man and teenage boy who were found guilty of the brutal act, and the aftermath of so many others who were touched by the tragedy. Coloring books and T-shirts have become the tawdry and unfortunate byproducts of a personal tragedy gone viral.

It would be easy to accuse Buting and Strang of cashing in. Their cross-continental tour will take them to the Beacon Theater in New York, the Berklee Performance Center in Boston, the Theater at Ace Hotel in L.A., the Sony Center in Toronto, the Chicago Theater, San Francisco’s Warfield, and on and on.

Nice work if you can get it.

Tickets for their opening night in Milwaukee were on the pricey side, from $45 to $65, and I half expected to see a merch table in the theater lobby, stocked with “Making a Murderer” baseball caps and Buting and Strang for president posters, maybe action figures of the lawyers in gray suits, posed to mightily launch a cross-examination.

But there was no self-promotion at all, except for a cursory mention of each of their law firms. A portion of their fees in fact will be donated to local and national equal justice initiatives. Rather than a chest-beating performance, Buting and Strang delivered what they had promised in the billing: a conversation on justice.

With a local journalist as moderator, the duo provided the requisite war stories, a director’s cut of the making of “Making a Murderer.” They maintained they never rehearsed for their on-camera moments, and admitted that their expectations of the film were low. Said Strang: “I thought, you know, 105 minutes long, shown in art houses in L.A. and New York, and seen by 17 people.”

Strang and Buting appeared genuinely uncomfortable with their roles as marquee names. “We have had other high-profile cases, but nothing like this,” said Buting. “The recognition we get just walking down the street is not typical. On the other hand, I do embrace the role model of good, honest defense attorney with integrity. To that extent, I’m willing to accept the inconvenience factor of having selfies taken on every block.”

Slamming the prosecution for releasing lurid details that allegedly described Halbach’s final moments, they castigated Special Prosecutor Ken Kratz for tainting the jury pool. And while they gave high marks to the filmmakers for raising valid questions about the prosecution of Avery, they said they would have liked more footage of their attack on the prosecution’s evidence. Where was the victim’s blood? And why was the prosecutor allowed to enter as evidence DNA from Avery’s sweat, supposedly found on the hood latch of Halbach’s car? “There’s no such thing as sweat DNA,” Buting insisted, and the crowd cheered.

But the conversation inevitably circled back to the shortfalls of the criminal justice system — the prevalence of police shootings of unarmed African-Americans, of life-without-parole sentences, of criminal prosecutions of juveniles in adult court, as seen in sharp detail in the documentary’s scene of 16-year-old Dassey being interrogated by police without the presence of a lawyer or a parent.

An opportunistic sideshow? I don’t think so. Their tour is a smart move to steer the “Making a Murderer” conversation to a higher ground. Although they lost the Avery case, Buting and Strang came away as creditable critics of the justice system. In an election year that’s richly topical and divisible, they’re in a unique position to speak out.

“The film does raise important questions about what we’re doing in our courts, about police operations in our communities, the role of class and poverty, the experience of juveniles,” said Strang, the contemplative one. “The questions are of overriding importance, as long as viewers keep in mind that this is not entertainment. It certainly is something to watch in your leisure time. I understand that. But in the richest sense of the word, this is not and should not be entertainment. But it can be useful in leading to a better informed public and a better informed dialogue about how we administer justice.”

It was the encore performance that the fans had been waiting to see.