In an episode of the Anthony Bourdain television program “No Reservations,” Jim Harrison offers a succinct summary of his beautifully subversive philosophy: “You have to follow the affections of your heart, and the truth of your imagination. Otherwise, you will feel badly.”

The sweeping transmission of pathos to pavement where high-minded thought meets the immediacy of everyday experience is accessible in the novels, novellas and poetry of one of America’s greatest living writers. Harrison has written with a prolific and workman consistency for several decades, telling stories as diverse as the lives of conservative women, which doubles as a satirical portrait of the sexual neuroses of the far right (“Republican Wives”), and the ribald, but intellectually probing account of an elderly werewolf (“The Games of Night”).

Harrison once remarked that he often “reads more for strength than pleasure.” Readers of Harrison’s books will find large quantities of both qualities, but the strength is there for anyone with a healthy streak of hedonism, a quiet appreciation for beauty, and disgust for America’s dominant value systems: Puritanism and careerism.

One of Harrison’s indelible and beloved heroes, Brown Dog, possesses all the principles and properties of the picaresque Harrison ethic, and the battles he fights delineate a worldview far out of step with the mainline of American culture. Brown Dog is a perpetually broke contrarian with a voracious appetite for food, nature, booze and women. His adventures include saving a young woman with developmental disabilities from permanent placement in a dreary and cold facility (Brown Dog drives by the building, and seeing that it has no flowers or foliage on the grounds, immediately decides that he will rescue this girl he has unofficially adopted), traveling from his home of Michigan to Hollywood in order to retrieve his bearskin rug from a documentary filmmaker who stole it, and sabotaging the academic research of anthropology students who plan to dig up a Native American burial ground.

Brown Dog, despite the importance of his struggles, is a libidinous trickster whose stories are equally comedic and dramatic. There are several consistencies in the highs and lows of Brown Dog and the more contemplative and melancholic literature in Harrison’s other books. Brilliantly and boldly, Harrison deals with man and woman’s relationship with the natural world; specifically how the priorities and practices of commerce extract people from the natural world, and sublimate their true instincts and impulses into socially acceptable, but ultimately empty pursuits.

In one of Harrison’s earliest and best novels, “A Good Day to Die,” three societal outsiders plan to blow up a newly constructed dam in order to combat the creeping dominance of machinery and industry over ecology. Most of Harrison’s stories lack the intensity and suspense of domestic terrorism. His plots are minimal and meandering, as the novels and novellas are heavy on character development and reflection. The narrative voice of Harrison is always comforting and inviting; akin to sitting down with an old friend who is full of bracing insight and brash humor.

The old friend is also one who reminds you that life is meant for enjoyment, pleasure and nourishment. It is not a ritual of sacrifice, or one long day at the mill or office. Similar to the wisdom of Sigmund Freud’s “Civilization and Its Discontents,” but much more entertaining, Harrison teaches that sexual pleasure is worthy of pursuit on its own, and that structure and discipline, while important, are also overrated.

Harrison’s characters lunge at life with gusto, and they eat, drink and fornicate with a sense of fun often missing in American life, where pleasure is under constant suspicion. They also think deeply and critically. In the novella “The Man Who Gave Up His Name,” a wealthy financier rejects his own riches, and the lifestyle of careerism and consumerism it enables, by donating all of his money to his daughter, and chasing his lifelong dream of culinary excellence. The story ends with him working as a chef in a small seafood restaurant on the Florida coast. Reminiscing on his failed marriage to a dancer – a woman he still loves – he dances with waitresses into the wee hours to the rock ‘n’ roll music emanating from the jukebox in a dive bar. Having found happiness and enrichment, he reaps the rewards of the courage to discover and know himself.

The characters who populate Harrison stories are as introspective as they are hedonistic, but their hedonism, for all their lusty encounters and impulsive behavior, is rarely, if ever, selfish. In an eschewal of the oversize individualism of American culture, Harrison’s characters feel deeply for other people, and other living things in general.

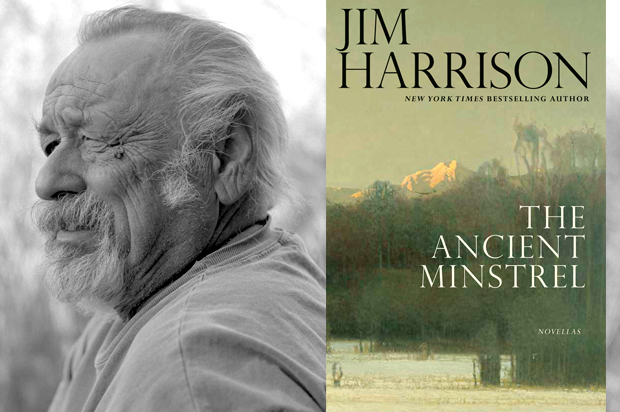

It is this very compassion that allows Harrison, against the odds, to write one of his greatest passages in his newest collection of novellas, “The Ancient Minstrel.” In the title novella, Harrison has fun with his own image by writing an autobiographical story about an “award winning poet.” Far from self-congratulation, the narrator explains that the awards his poetry has won are ones he has never heard of, and when he showed up to collect them, the banquet halls were half-empty.

In a fictionalized update to Harrison’s memoir, the “award winning poet” is now separated from his wife of many years, and struggling with what he perceives as the limitations of his talent, which he believes has diminished with age. He lives on a large ranch in Montana, and impulsively buys a sow. The gigantic female pig soon has a litter of piglets, and Harrison begins to fantasize about his life with them, most especially the “little runt” he names Alice. As it so often happens, the random nature of life and the world – capable of great cruelty in its indifference to human aspiration and connection – is disruptive.

When the sow rolls over and accidentally kills Alice, the “award winning poet” sobs:

He carried her little body into the studio and put her on the desk. He had intended her to be his best friend. They would take walks together every day and if she got tired he would carry her home like he had done with one of his dogs. He wrapped her carefully in a big red bandanna thinking that she was yet another of the deep injustices of life. He dug a hole near the pen and decorated it with a circle of rocks. He put her wrapped body down in the hole, dropped a handful of earth on it, and said an actual prayer for the deliverance of her soul. He had crisscrossed two yellow pencils in the shape of a cross, glued them together, and stuck them in Alice’s grave.

The narrator writes that he is pleased he “didn’t separate his own life from that of Alice.” He wonders where he, and others, ever got the idea that “writers were so important in the destiny of man?” Maybe Shakespeare qualifies, he speculates, but otherwise it is vanity, and “perhaps the influence of religion,” to believe that you – regardless of who the “you” is – are more important than other creatures. He them remembers, fondly and with pride, one afternoon when he interrupted his own work to free a wasp trapped behind a window shade in his studio. Who was to say that wasps, Harrison asks, “are less important than a writer struggling for fame?”

The insight Harrison, in the form of his slightly fictionalized narrator, is able to draw from Alice’s death, and the emancipation of an imprisoned wasp, distinguish those moments as what the writer calls “glimpses.”

Glimpses occur in those rare moments when “reality can break open and reveal its essence like bending linoleum until it broke and then you saw the black fiber underlying it.

It is fascinating that the Harrison narrator claims that “glimpses” is his “theory in early development,” because his entire career is a catalog of glimpses. The power of the glimpse is the reason why his writing, from young to old, maintains an almost primal level of visceral awakening and aggression.

In “The Games of Night,” the elderly werewolf teaches that “culture is the layer of paint we apply over human nature.” America’s lead-filled layers of Puritanism, careerism and consumerism cannot compete with the flashes of brilliance Harrison’s characters discover in deep moments of true feeling: sexual intimacy, love, the beauty of nature and the triumph of making the longings of passion an immediate reality. Moments of disappointment and loss are also important, as Harrison writes: “Death gets our attention.”

The value and pleasure of literature is the discovery of glimpses. Despite the rapid pace of contemporary culture, and the deceptive appeal of the audio-visual, literary art remains important in its edification, because, at its best, it can reorient and rearrange the priorities of the intellect to concentrate on what truly matters, and what truly makes our lives worth living.

In this sense and many others, as he rides against the wind of American culture, the “award winning poet” is most deserving.