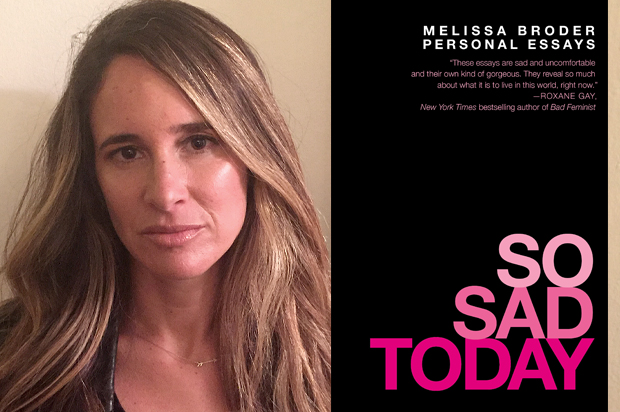

Melissa Broder is easy to talk to. The poet and author of “So Sad Today,” a book of essays that expand on the themes she mulled over in her popular Twitter account of the same name, is “a sharer,” she says, a natural at self-confession who invites the same in others. Within seconds of getting her on the phone, we were talking about my rescue dog’s personality issues, and her dog’s as well. “He’s definitely got anxiety,” Broder said of her dog, adding that she hasn’t yet shared her anxiety drugs with him.

“So Sad Today” contains essays about sex and death, anxiety and depression, addiction and meditation – the same concerns that animate her three poetry collections, “Scarecrone,” “Meat Heart” and “When You Say One Thing But Mean Your Mother.” (A fourth poetry collection, “Last Sext,” is forthcoming this summer.)

Broder writes with the kind of honesty that can make you cringe and laugh, and then catch your breath, brought up short by a kind of existential dread.

Your book takes its title from the Twitter account that you started anonymously. Why did you decide to do that?

I’d gone through periods of anxiety in my life, where the panic attacks were more intense or less intense, basically I would get into these cycles. I was going through a particularly harrowing cycle of anxiety – it was fall 2012 – and I would go into work and I would be afraid that I literally couldn’t even sit there. I’m kind of a perfectionist, and I catastrophize, so I was like, well, if I can’t sit here, how am I going to come back in tomorrow, and if I can’t come back in tomorrow how am I going to work, and if I can’t work, then how am I going to support myself – it would sort of spin out into the ultimate worst-case scenario.

I was just really scared. And I also had a lot of depression under that, which I didn’t even realize was depression. My anxiety was such a nice cover for it. I feel that’s one way that anxiety can sort of serve us, like it can protect us from other feelings that maybe we’re not able or willing to handle. Because anxiety can feel so bad – in my mind it’s my worst enemy – but there’s probably part of me that must prefer feeling anxiety to depression or other emotions. Because it’s sort of where I default.

Is it that perhaps anxiety’s also a little more entertaining than depression, like you can share it more with others?

Well, it’s more active. So where, even though anxiety can feel like a captor, I think there’s a lot going on and you can also harness anxiety to kind of propel yourself forward, whereas I feel like with depression, I feel more buried by it. It’s scarier for me to feel buried than to feel whipped.

It’s funny: We call these things depression, or anxiety disorder, but there’s probably just this huge range. People experience depression in all different ways. I wouldn’t even say that mine is necessarily sadness; for me it’s more like terror. We compartmentalize these things into neat little pockets, or we try to. We give them diagnoses.

So at that time, I was going through these cycles. All the things I normally did to get out of this place were not working. And my mind was like, you’re going to be in this forever. So I found this creative solution. It was going to be a place where I felt like I was going to be compulsively tweeting, as a repository for all this shit. I didn’t have any followers at first, was just tweeting out into this abyss, and then gradually people started following. I stayed anonymous from 2012 to 2015. So I was anonymous for the bulk of the time.

How did that process – having this account that’s anonymous, but you’re sharing real, intimate feelings – what does that do to your anxiety levels? Did that dispel your anxiety, that you could share, or was it scary in its own way?

Well, it just gave me an outlet. Therapy has never felt anonymous enough to me. Lately I’ve been better about this, but it’s always been hard for me to drop that need to perform. It’s like, I’m okay until someone sees that I’m not okay, and once somebody recognizes that I’m not okay, then I’m really not okay.

Right, because you also want your therapist to like you – you don’t want your therapist to be alarmed about how you’re doing.

Yeah. Totally. And I’ve had so many panic attacks in therapy, but I never tell them, because I don’t want them to feel like something’s wrong with them. Why would I have a panic attack in therapy? It’s supposed to be a safe space –

But don’t they know? Wouldn’t a good therapist recognize that you’re having a panic attack?

No, that’s the thing! Actually I get kind of sad when they don’t; it’s just another way of feeling separate from humanity, right, like I’m like “oh my god, they totally didn’t know!”

That’s so sad if they can’t tell. It’s like you’re faking an orgasm and your partner doesn’t even know…

Exactly. But the thing is, I’ve been having panic attacks for 15 years so I’ve gotten really good at nobody knowing I’m having one. I can be in throes – all the symptoms can be happening, the rapid heartbeat, the suffocating sensation. For me it really centers a lot in my breathing. I feel like I’m suffocating, my throat is closing in, I start to feel dizzy. The scariest one is when it kind of progresses and I get a sense of unreality, like I’m looking at the person and it’s sort of like I’m on acid, there’s a hyper realness, or an unrealness, like I’m looking at them and I feel very dissociative. And that’s when it gets very existential. Like Camus said, at any moment, at any time, the absurdity of the world can slap a man on the face – I’m paraphrasing – or when Burroughs talks about seeing the lunch on the end of your spoon. It’s like when your context shifts and you’re like, what is all this, what are we doing?

But you can be feeling all that and nobody knows? You have that kind of a poker face? That’s amazing, it’s impressive…

I was telling my therapist last week that I’d had a panic attack with her the week before. This is one of the first times I’ve come clean; I have a new therapist, and I like her a lot. And then a few weeks into it, I had a panic attack in her office. It was really because I hadn’t eaten yet that day, my blood sugar was really low, I hadn’t slept the night before, I’d been up writing. And who knows what the topic was that we’d been talking about. But I just got one of the sensations and my mind was like, “What’s wrong? Are you dying? Yes, you’re dying.”

And the next week I told her – I didn’t want to tell her – I felt like kind of disappointed in myself that I hadn’t told her as it was happening, because I kind of made a new rule, like, if you’re not going to be honest with the therapist, then why are you there? But it’s hard, when you’re going through it, it’s a very isolating experience. You feel super alone in it. I don’t really want to voice it, because if I voice it, then it’s really happening. As much as I tweet about it, in real life I still have a lot of shame about it, even after all these years. So I told her, and she was like, I had no idea.

Having this anonymous So Sad Today account, did that enable you to express anxiety in a way that felt safe?

Yeah. I mean, that’s what it was. In my everyday construct of my identity, my social life, my professional life – there was a need to keep a mask on. So Twitter felt like a place where I could be really, really, really real. But I had to be totally anonymous. That’s the only way I felt safe to be really true and real.

And so you unveiled yourself a few months back, and now this book is out and it’s got your name on it, and you’re sharing stuff that feels really intimate. I mean, how scary is that?

Well, I mean I’ve definitely talked about it in therapy! For about two and a half years I didn’t tell anyone and it’s like really the only secret I’ve kept. I’m not a good secret keeper. I’m a sharer. I’m not exactly like buttoned up.

So then I told one person and it was weird because the difference between it being totally anonymous and one – that was like a big deal. Suddenly I knew one person knew and I felt like I could be judged. And then I was nervous to tell, I was really nervous, I was afraid that I would be a disappointment, that the fans of the account would be like, “oh….” The thing I have the most anxiety around now is that, like, my parents are not allowed to read this book.

But how can you stop them? I mean, not to scare you, but someday your parents, or your parents’ friends, or someone you know will read that chapter on your vomit fetish.

That was the one chapter that after the galleys came out I had cold feet and I talked to my editor and agent and I was as like, OK, this is too much, too much honesty. That was the scariest chapter for me to write. That was like a secret since I was a little kid. It’s like those old secrets that you have, that might not be the biggest deal, or filthiest thing about you, or the most fucked up thing about you, but for some reason it has like this youthful shame to it.

You just don’t need to know everything about your child. I mean, people don’t need to know everything about you. So, why was I so confessional in this book? And I think it was almost like an exercise in some way – to confess everything, or a lot of everything. It’s funny, because what we confess is still controlled. You’re still wearing a mask. Do we ever take our mask off, even for ourselves? I don’t know that we do.

I don’t know that we could handle it.

It’s a lot, that much self-realization at once. If it’s even possible. It’s like, if one believes in God to see all of God at once. Or like, in “Moby-Dick,” to see the whole whale.

And so it was sort of an exercise in – in the same vein that if I worry about something, I have this illusion of control about it, like it won’t happen if I worry about it. So like, if I can confess something, and not be judged, then maybe I can accept this in myself. It may not be a logical thing. But I was challenging myself.

It wasn’t until it was in galleys until I was like, oh shit.

What’s your poetry like? Are you as confessional in that work as you are here?

My poetry contends with a lot of the same themes as “So Sad Today.” Very obsessed with sex, death, longing, filling the existential voids of our lives. Our obsessions are our obsessions; we can’t really escape them. But I really like to use language that’s very primal. I don’t like using language that’s in any way pop-cultural or disposable. I like language that’s very timeless. I have this book coming out this summer from Tin House, called “Last Sext,” and it’s a very poppy title but the only word in the entire book that I think you wouldn’t have been able to understand 100 years ago.

Are you working on more stuff? New poems? New essays?

Well, I always considered myself a poet, and I’m always writing poems. When I lived in New York, my practice of writing poetry was that I wrote a lot on long walks, I wrote on the subway, I wrote using my phone. I like to write in motion; I don’t like to sit at my desk and write; it feels too formal. I like to write when I’m not supposed to be writing.

Actually I’m working on a very long piece that’s fictional. That is contending with those same obsessions but through a different medium. It might be a piece of shit. It might be horrific. I’m always writing. I kind of feel like I have to. It’s something to live for.

So that’s where the meaning is. If life is a well of meaninglessness, then maybe writing is the meaning.

Yeah. I think it just – the nonfiction helps me feel like I have some control over my narrative. I could be going through shit and kind of write my way out of it, or share it with others and it makes me feel like I have some control, if only to put it into my own words.

And poetry, that feels like alchemy. It’s a way for me to access the magic of life – I mean the thing that I want, which is to always feel like I’m in some kind of flow. You know, I’m an addict; I always want to feel high. I have trouble with the mundane. It doesn’t feel like enough to me. There’s other things you can do when life doesn’t feel like enough – you can drink, you can have sex, you can get high, you can overindulge in food, you can go shopping for shit you don’t need. There are all these things we do to as life enhancers. But the longer I’ve been sober, the narrower the road gets in terms of things I can do and still kind of – and not be aware that that’s what I’m doing.

Do you think writing is an addiction then?

Well, for me, it’s the only one that hasn’t tried to kill me.