Less than a 100 years ago, the practice of sterilizing Americans seen as unfit was widespread. A new book, “Imbeciles,” looks at the issue through one heart-rending 1927 court case that collects so much that was sad, bad and misguided into one specific time and place.

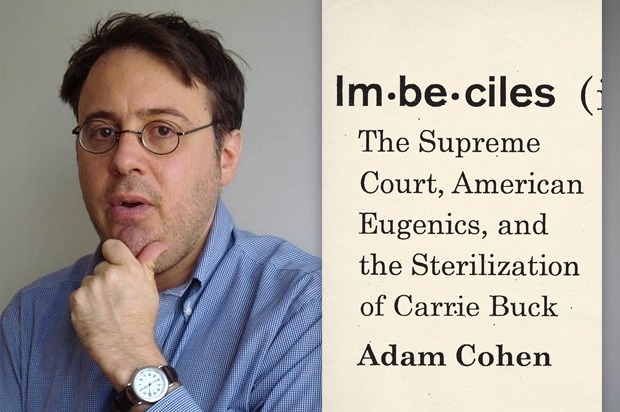

Subtitled “The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck,” the book looks at the Buck v. Bell case, which concluded with the court allowing Virginia to sterilize a poor, luckless teenager. Author Adam Cohen tells the story close-up, by drawing Buck, a doctor, a prominent eugenic scientist, a lawyer and Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in detail. Holmes famously wrote in the court’s majority decision that “Three generations of imbeciles is enough.”

In the background of the story – and sometimes its foreground – is the American fascination with eugenics, the belief in improving the human race through selective breeding. In its heyday, support for eugenics was mainstream, and its advocates included progressive figures like Teddy Roosevelt and Margaret Sanger.

Cohen is a former assistant editorial page editor for the New York Times and the author of the well-regarded “Nothing to Fear: FDR’s Inner Circle and the Hundred Days That Created Modern America.” The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Let’s start with the idea of sterilization. What was the justification for this in the early 20th century?

In the early part of the 20th century, eugenics was actually a very popular idea. There was a broad feeling in the country that the nation’s gene pool was threatened, and that it was necessary to take action to uplift the nation and humanity. To get better people to reproduce, and worse people not to.

So sterilization was one of the tactics they came up with to improve the gene pool.

And what kind of people were in favor of it, and disseminated the idea?

This was an idea very popular among progressives in the country. Universities were very prominent in promoting sterilization, so, for example, president emeritus Eliot of Harvard University, who was a revered figure, wrote an article supporting eugenic sterilization. The medical profession was a big supporter of sterilization. So some of the most educated and progressive parts of the country were in favor of it.

How widespread was this idea that we could improve the race by limiting reproduction? It was not just a fringe-y idea in the ‘20s.

Not at all – it was widely popular. Indiana passed the first eugenic sterilization law, in 1907… And many other states followed. There was broad support.

Eugenics as a topic was broadly popular; it was taught at over 300 colleges and universities including Harvard and Berkeley. It was talked about a lot in popular magazines. In my book I quote Cosmopolitan magazine saying what a great thing eugenics was and how it will make the race better. So this was widely popular and winning majoritarian support in places like state legislatures.

Tell us a little about Carrie Buck, the central figure in your book.

She’s a very sad figure – a victim of this movement. She was born into a poor family in Charlottesville, Virginia, and raised by a single mother. Back at that time there was a lot of thought that it was better for poor children to be raised in middle-class homes, so she was taken in by a foster family…. They didn’t treat her very well…

And then one summer she was raped by the nephew of her foster mother. So she was pregnant out of wedlock and her family was eager to get rid of her, both because of the stigma of out-of-wedlock pregnancy but also because their relative had committed a crime. So they got her declared epileptic and feeble-minded; she was neither… She’d been doing perfectly well in school.

She’s then sent to the Colony For Epileptics and Feeble-Minded.

She’d had a lot of bad luck in her short life, and continued. She got there just after Virginia had passed its eugenics and sterilization law, and they were looking for someone to put in the middle of a test case. The decision had been made in Virginia hospitals that they did not want to sterilize people until the law had been tested in the courts.

The Colony president chose Carrie as the test case. She’s put in the middle of the story.

You write about a broad, sweeping topic and a set of moral concerns. Why did it make sense to tell it through a court case and five main characters?

There are so many ways to tell a story, and the eugenics story is such a sprawling one in the United States.

One reason I fixed on this is that it shows just how strongly the nation adopted it and how wrong we were as a country. It might not be shocking to hear that in 1920s there was a doctor in Virginia, at some benighted colony for epileptics and the feeble-minded who was sterilizing people…

What’s shocking is that when this was brought to the U.S. Supreme Court, the chief justice was a former president of the United States – William Howard Taft. The court included Louis Brandeis, one of the greatest progressive heroes ever to serve. And the decision was written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, the great justice.

That really shows, at a much higher level, our societal breakdown. This was not a few wrong-headed people. At the point in our society, where we expected justice to be meted out – the U.S. Supreme Court – it wasn’t even close. It was just a horrible decision.

But also the book is a story about justice, and that we don’t provide the kind of justice that we claim to in our society.

Buck v. Bell is in part a eugenics story, but it’s also part of a larger Supreme Court story, where – as I talk about a little bit in the book – that we like to think that justice prevails, that the strong people in society are not allowed to harm the weak. But over and over again, the court has failed to do that.

Your book is mostly concerned about a specific moment in time. But sterilization certainly didn’t go away. How long did it continue? It sounds like it continued almost right up to the present.

It’s shocking. Eugenic sterilization – done under the auspices of a eugenics office in a state – continued until Oregon did the last one in 1981. We know it’s still done, not in [accordance] with these laws but more [underground]. A few years ago it came out that there was a lot of sterilization going on at some California prisons. There was a case in which a Tennessee prosecutor was fired, a few years ago, for making sterilization part of his plea negotiation for female defendants.

So there’s probably more of this still going on.

There was a moment where the movement lost steam – with the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s. As the Nazis talked more and more about the Aryan race, the master race, and talked in eugenic terms, it actually made Americans pretty queasy about it. The major eugenics office in the United States, on Long Island, began to lose its funding in the 1930s and shut down in 1939, because of that.

But at the same time, that did not stop eugenic sterilization from occurring. In Virginia, where the Carrie Buck story unfolded, Nazism tainted the movement but it did not entirely obliterate it.