For all Donald Trump’s dark pronouncements about immigrants and Muslims and the sporadic fistfights at his rallies, the Republican frontrunner has so far channeled the rage and fear felt by his constituents into an election campaign. Violence is never far from the surface at a Trump rally, and as has happened with sickening regularity in recent weeks, it occasionally breaks through in wild sucker punches and outright beatings of protesters, but the goal of the Trump campaign could not be more conventionally political: to propel its candidate to the Republican Party nomination, and from there, to the presidency.

But what happens when his campaign fails, as it almost certainly will? Trump is openly at war with his own party, and even if that badly splintered organization magically unites behind him after the convention, there simply are not enough angry white people in America to elect him president. Where will all that anger, which has been slowly building among America’s white working class for half a century, go once it is left without a viable political outlet?

In the months since Donald Trump’s presidential campaign has shifted from amusing diversion to cold political reality, the narrative favored by America’s political and media elite has been one of chickens coming home to roost. The Republican Party, the story goes, having for too long cynically played upon the ignorance and fears of its white lower-middle class base to gain the votes to pass ever more lavish tax breaks for its wealthy donor class, has had its electorate stolen by a clownish billionaire willing to say in plain English what Republican leaders have for decades been communicating to their constituents only in whispers and dog whistles.

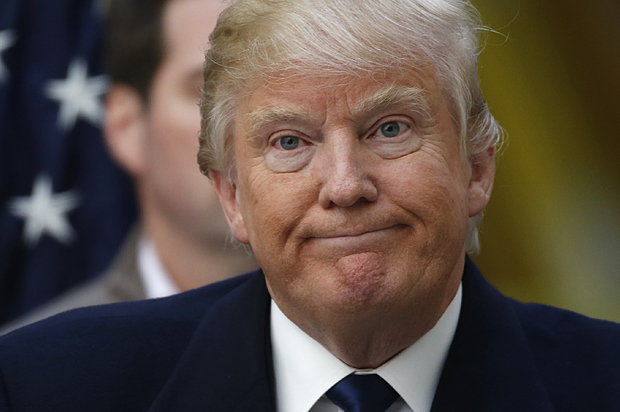

This narrative is true, of course, but in the telling, the focus invariably falls on Trump, who is portrayed as a shameless but politically astute demagogue in the mold of Louisiana’s Huey Long or Alabama’s George Wallace, able to sniff out deep wounds in the body politic others have missed and transform them into votes. But this is absurd. For all his bluster, Trump is at best a mediocre politician. He has no core political philosophy, he rambles at the podium, and quails at even the mildest questioning from the press. Half the time, he doesn’t even seem that interested in the office he’s running for. The night he won the Florida primary, knocking the home-state Senator Marco Rubio out of the race and cementing his position as his party’s frontrunner, Trump spent much of his prime-time televised speech touting his eponymous line of steaks and wines.

Trump is the P.T. Barnum of 21st century American politics, a gifted impresario able to spot a sucker a mile off, but he isn’t the phenomenon we should be watching this spring. His constituency is. Lower-middle class white voters from the Rust Belt and South have fallen under the sway of Republican leaders for more than half a century now. In some cases, those Republicans were brilliant politicians like Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. Just as often, though, white working class voters pulled the lever for empty suits like Mitt Romney and George W. Bush.

What changed, then, in 2016? It wasn’t the Republican Party’s strategy or the quality of the candidates it put forward. Jeb Bush, with his jaunty exclamation point and famous last name, was a more substantive version of his twice-elected younger brother, and Ted Cruz has the sweaty, aggrievement-fueled intensity of a young Richard Nixon. In any other election cycle, one of them, most likely Jeb Bush, would be honing his acceptance speech by now.

That didn’t happen this year because lower-middle class white Americans are hurting as they never have before. No group, after all, has been hit harder by globalization than the white working class in the Rust Belt and South. Drug addiction, long considered an “urban” (read: African American) scourge, is spreading through white society, especially in rural areas and former industrial hubs. A recent study by a pair of Princeton researchers found that, alone among all cohorts of Americans, the death rate for white middle-class people has been rising, thanks to spikes in alcoholism, drug overdose, and suicide.

It’s easy to argue that working-class white Americans have no one to blame for their predicament but themselves. For generations, white people were favored in virtually every area of American life. Then, thanks in part to liberal legislation and court rulings, America became more color-blind and meritocratic, while at the same time free-trade agreements helped push factories overseas, hollowing out whole towns. The wiser children of factory workers got an education and joined the information economy. Those who stuck it out in the industrial heartland hoping the mid-century American gravy train would return instead got left behind.

This, obviously, is not how Trump’s white working-class constituency sees it. They blame 1960s-era legislation and court rulings for promoting the interests of minorities and immigrants over their own, just as they blame the free-trade policies of both parties for sending their jobs offshore. Their economic power waning and their social status under threat, they lash out at the minorities and immigrants themselves, fearful that these once lower-caste workers are fast climbing past them on the ladder of American society.

Ultimately, though, whether one views Trump’s supporters as victims of American progress or as a bunch of overprivileged bigots matters less than the undeniable facts that they exist and there a lot of them and they are stuck. Having lost faith in the traditional Republican Party, they have pinned their hopes on Donald Trump, but even if Trump could deliver the jobs and self-respect they seek – a doubtful proposition, to say the least – they lack the numbers to make him president. So, then what? All that highly combustible anger and fear we’re seeing on the nightly news and in shaky YouTube videos shot at Trump rallies – where will it go once Trump is gone?

We may already be getting a chilling preview of a possible post-Trump future in the spasms of seemingly random gun violence such as those at the Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs and the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston. Neither of these alleged shooters has been brought to trial and there is much we do not know, but what is clear is that we are in the midst of an unprecedented epidemic of mass shootings, a disturbing number of which seem to be carried out recently by emotionally troubled white men harboring right-wing views.

For a generation, gun advocates have defended the right to bear arms as a check against tyranny, and for just as long liberals have dismissed this as a melodramatic talking point. But what if we take them at their word, and accept that it is possible we are witnessing the opening phase of a still-inchoate violent uprising by a broad class of Americans, who, ignored politically, bypassed economically, and dismissed socially, are beginning to take matters into their own hands?

What if, in other words, Donald Trump isn’t an aberration created by the miscalculations of a party elite, but the political expression of a much deeper, and more dangerous, frustration among a very large, well-armed segment of our population? What if Trump isn’t a proto-Mussolini, but rather a regrettably short finger in the dike holding back a flood of white violence and anger this country hasn’t seen since the long economic boom of the 1950s and ’60s helped put an end to the Jim Crow era?

One way or another, we’re going to find out soon. Trump made headlines when he suggested his supporters would riot if he were denied the nomination despite his lead in the delegate count. Even if we are spared that spectacle, the Trump era will almost certainly come to an end by November. And then we will be left with the naked fact of his followers, too few in number to effect meaningful change on their own, too numerous for the rest of us to ignore, too angry to sit still for long.