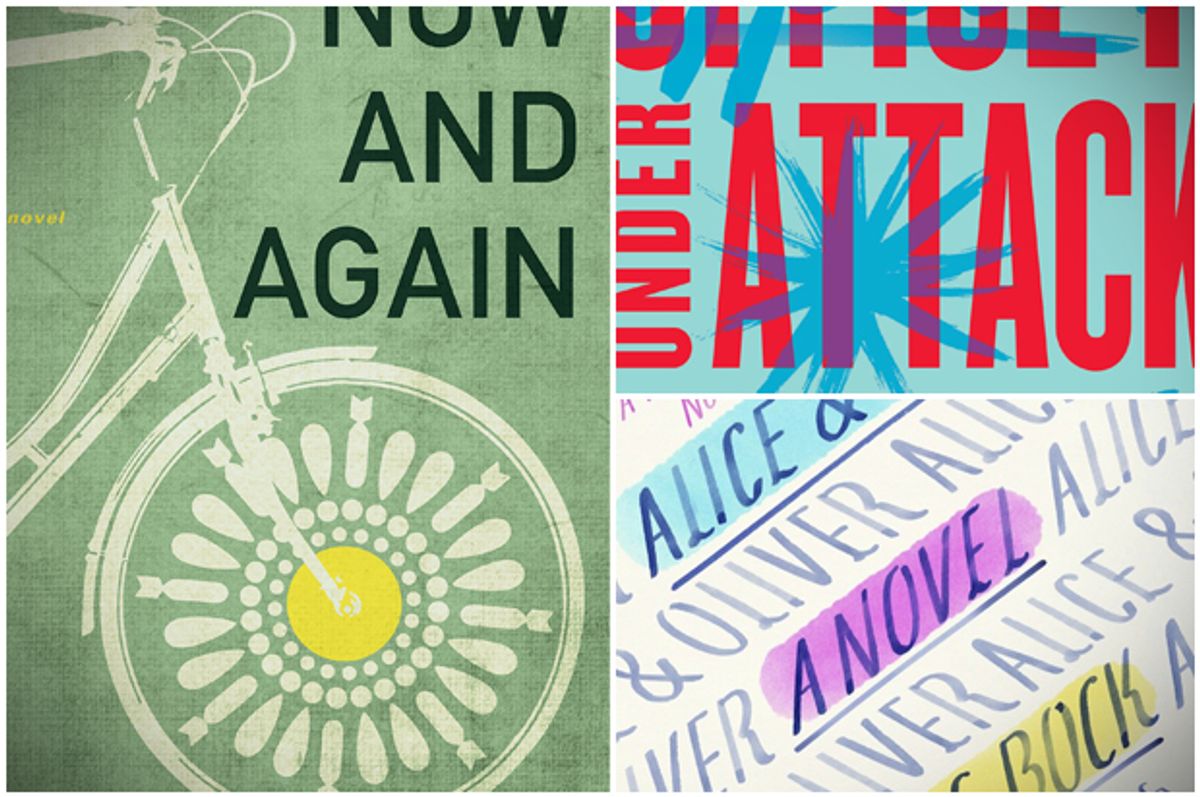

For April, I posed a series of questions — with, as always, a few verbal restrictions — to five authors with new books: Charles Bock (“Alice and Oliver”), Manuel Gonzales (“The Regional Office is Under Attack!"), Charlotte Rogan (“Now and Again”), Rebecca Schiff (“The Bed Moved”), and Rob Spillman ("All Tomorrow’s Parties”).

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

SCHIFF: This book is about resenting not having enough sex, and then having too much sex and resenting that, too.

BOCK: What do we owe ourselves; what do we owe to those we love; how am I supposed to move through this world and these competing urges when my time is finite?

GONZALES: The Regional Office is at its core a book about revenge and a book about how awful it is sometimes to get what you want.

SPILLMAN: Berlin in the Sixties, Berlin in 1990, the East Village in the late Eighties, opera, punk rock, the search for authenticity.

ROGAN: Ordinary people who start to pay attention to what is going on around them—now that they know, what do they do? How hard it is to tell which information is correct and which is misinformation or outright lies. Whistleblowers. People who want to make the world a better place. History repeats itself. Eternal return.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

ROGAN: A 2004 blog post, Gulf War syndrome, Edward Snowden, the American incarceration rate, our ambivalence toward do-gooders, Peter Singer and the expanding circle, sea to shining sea, the novel as world-building, gospel music, rootedness/unrootedness, idealism, Kierkegaard: “Do it or don’t do it, you will regret both.”

GONZALES: "La Femme Nikita" -- the movie, not the show -- and “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” -- the show, not the movie -- and the two-part episode of “Alias” from season 1 featuring a cameo from Quentin Tarantino. Also a couple of books that dove into the culture of working in an office. And let's not forget the Hayley Mills classic "The Parent Trap," and the Bruce Willis classic "Die Hard."

SCHIFF: Hot springs, catered events, cordless phones, the way my parents were when I was young.

BOCK: Oncology wards and everything that happens in them; hospital waiting rooms; IV machine battery packs; portable diaper-changing kits; breast feeding; the old Tuesday afternoon lines at Astor Place where you waited for the Village Voice classifieds; late nights together on the couch when the child is asleep; John Starks going 2-18 in game seven of the NBA Finals.

SPILLMAN: A soundtrack with 67 tracks, one per chapter. The Beats, the New York School, Berlin in the Twenties, “He forces you to use the word beautiful”—Robert Motherwell on Joseph Cornell.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

SPILLMAN: Writing on planes, receiving 20,000 submissions per year, meditation on long bike rides, multiple nonprofit boards, reviewing, interviewing other authors on stages and at bookstores, two very different teenagers.

ROGAN: Kids off to college and jobs, home again, off again, home again, a lot of moves and rescue missions, the publication of my first novel at age 58, connecting with other book people, good and bad medical advice, angst about the state of the world, a border collie who found me on the Internet, thank god.

GONZALES: A poorly conceived turn at managing employees; more influence over important matters handed over to me than was necessarily wise; a move (my family and me to Kentucky); a move (my editor to a different publisher).

SCHIFF: Dumped guys in their own beds, had to take taxis home from dumping them, moved within Brooklyn, taught essay writing by the sea, mom had breast cancer, dad stayed already dead.

BOCK: Ha.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

BOCK: How about this anecdote, instead: just before takeoff on an airplane flight, a stewardess reminded Muhammad Ali to fasten his seat belt. "Superman don't need no seat belt,” Ali answered. The stewardess looked at the champ: “Superman don’t need no airplane, either.” Which is to say: you get on the plane, you buckle up. (E.g. Omar Little: "All in the game, yo. It’s all in the game.”)

ROGAN: “Huh.” Actually, I don’t dislike the word—I just don’t want someone to say it about my work. “Wow” is the exact opposite—I’m not crazy about the word, but I’m always thrilled to hear a reader say it.

GONZALES: Someone once wrote that the novel was irrelevant, which. Irrelevant to what? To whom? In what way? How? It was just maybe the least relevant thing to say about anyone's book.

SCHIFF: A guy in my MFA program once described my stories as "cutesy." But he was illustrating his stories, so I thought that was cutesier.

SPILLMAN: I have every possible negative review mentally cataloged in preparation for snark.

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

ROGAN: Astrophysicist—or Alan Dershowitz.

GONZALES: The CIA, the FBI, or forensic anthropologist.

SPILLMAN: Head of an NGO that has tangible global impact.

SCHIFF: I would be a therapist.

BOCK: Well, I’ve chosen this. Really, I've worked my whole adult life at fiction, to try and write fiction. I’m more than fine with this profession, however limited its material attentions and remuneration. But it’s interesting. Chris Adrian is a tremendous fiction writer and a child oncologist at the same time (probably he deserves some form of sainthood). Sheri Fink has a medical degree and has reported some of the most important medical stories of our era. Atul Gawande; Chekhov; William Carlos Williams — top-tier journalists and essayists and novelists and playwrights who’ve also been doctors. I flatter myself to even imagine I could have had a medical practice; there’s no way; I’m not scientific or disciplined enough, lots of things. I’d hypothetically choose that, I guess. I feel the same way about charity workers. It’s nice to flatter myself with the idea I might have chosen those altruistic roads. Probably I would have chosen a stand-up comedian or NBA point guard.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

SCHIFF: Is voice part of craft? I'm pretty good at voice. I can hear my own thought rhythms and translate them to the page. I'm okay at dialogue. I'd like to get better at letting other characters be more than foils for my narrators. I'd like to try a third-person romp.

SPILLMAN: Structure. Yet, I wish that I was less logical and more emotional, more poetic.

GONZALES: I feel I am strong at describing action, writing dialogue, and making uncomfortable situations uncomfortably funny. I would like to be better at describing things that aren't action -- people, places, a table in a room, etc.

BOCK: My lanyard game is mad hot, and I promise I bring the truth with regards to rope bracelets. For improvement? Quilting. My quilting is dookie. All needlepoint-related things, I should do better on, being honest.

ROGAN: I am pretty good at dialogue and moving between the various novel elements so that none of them go on too long. I am good at not writing physical descriptions of my characters—I mostly don’t see the need for them. Plotting is hard for me—I would like to get better at that.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

GONZALES: I contend with this kind of hubris through illusions of grandeur and by the fact that I'm a megalomaniac and kind of assume that people will be interested in just about everything I have to say? Despite all evidence to the contrary? Despite having eye-rolling (but absolutely lovely) children who place little stock in what I have to say?

ROGAN: I imagine my trial—not for the crime of writing, which I did very quietly for 25 years, but for finally daring to publish. Usually this happens at night, or at twilight—fall and winter are the worst. I devise long speeches for my defense. It also helps to listen to online lectures about literary theory—now those are writers who should be worried about losing people’s interest!

BOCK: My man Ossip Mandelstam has a thought that sometimes helps: “I divide all the works of world literature into those written with and without permission. The first are trash, the second — stolen air.”

SCHIFF: Ha. This may be hubris, but I actually think that keeping my thoughts to myself is kind of stingy. I like to think that I'm sharing something personal/universal and that the people who need what I'm saying will find me.

SPILLMAN: When I was sixteen, reading about other possibilities—via Ken Kesey, Kurt Vonnegut, Virginia Woolf—saved my life. I’m hoping that there is one sixteen year-old like me that I can reach.

Shares