The novelist Ethan Canin and I first met in the fall of 2001, in Iowa City, about a week before the World Trade Center fell and the country was plunged into a decade of war and economic turmoil. At the time, I was twenty-three, unemployed, semi-homeless and recently convinced, for reasons I couldn’t quite articulate then and still can’t articulate today, that the only calling in which I might find fulfillment was the writing of literature, specifically at the time, the writing of literary fiction.

I arrived in Iowa City by way of San Francisco, a city that, in 2000, had seemed a place of endless opportunity and infinite ways to make boat-loads of cash if only you connected with the right people. I never did, and instead, ended my tenure in the city broke, lonely, and suffering from a bad case of pericarditis, an inflammation of the lining of the heart resulting from an untreated case of strep throat. Whenever I’d lie down, which I did often, it felt as though someone were placing a large water balloon on top of my chest. I literally left the city with a heavy heart, eager to start my adult life as a writer in Iowa, eager to find a mentor, someone who could guide me in this pursuit about which I knew so little.

During my first few days there, I bought all the books of the writers on faculty and read them in my shower-less, rented room. Lying on the mangy carpet with mugs of tea, I read Frank Conroy’s “Stop Time” and Marilyn Robinson’s “Housekeeping.” I read James McPherson’s “Elbow Room” and Samantha Chang’s “Hunger.” I found all of these books to be powerful and moving. And then I began reading the early work of Ethan Canin, his collection of stories, “The Emperor of the Air,” and his collection of novellas, “The Palace Thief,” and I felt something else, something different, something that clarified for me in a way not much else has, what it was exactly I wanted from fiction both as a writer and a reader, the thing that I sought and yearned for enough to give up any notions of a conventional, professional life in pursuit of what, if we’re honest, is a truly odd, obscure, and largely ignored art form. The thing that I found in that work was darkness: an honest and unflinching willingness to explore not just the darkness in the subjects in which we’re used to encountering it, but also, and more disturbingly, in our families, our ambitions, our values, ourselves.

This writer presented a view of middle-class American family life that I found both unsettling and deeply resonant. Unlike the work of many of the mid-century to late-century American realists I’d read at the time, Canin didn’t seem to be writing about broken or dysfunctional families. He wasn’t writing about addicts or outcast or the obviously mentally disturbed. The characters he presents are, in many ways, wholesome, good-natured, and successful. They are “likable,” and speak in a confident, balanced, often contemplative or retrospective voice. The characters have families they claim to love, jobs they claim to care about, respectable, American lives and ambitions. And yet, beneath the surface of all this optimism and what at times seems an almost corn-fed wholesomeness, they are often, like so many of the actual people we encounter in life, motivated by jealousy, greed, insecurity, shame, and an unquenchable thirst for worldly affirmation. They love one of their children more than the others. They wonder if the lives they lived so carefully and deliberately add up to anything at all. They muse on and reveal both the subtle and profound ways we disparage, humiliate, and emotionally wound those in our lives we claim to love most. They hold a mirror to the parts of ourselves we most want to keep hidden.

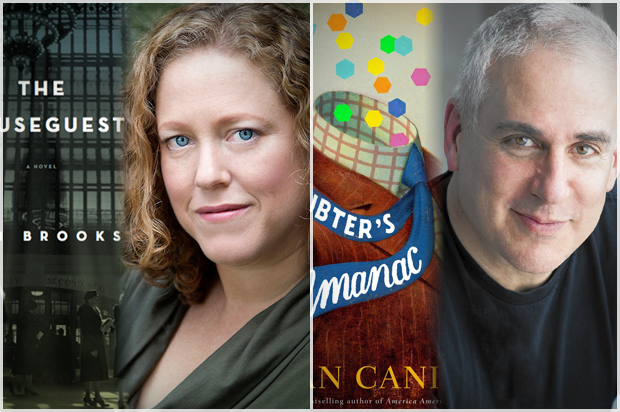

I found myself remembering this first impression I had of his work all those years ago a few weeks back as I returned to Iowa City to talk with Ethan about writing, darkness in fiction, the cost of ambition, his most recent novel, “A Doubter’s Almanac,” and my debut novel, “The Houseguest.“

KB: It occurred to me, Ethan, that one thing our books have in common is that it took us both a very long time to write them. You’ve said yours took about seven or eight years. For me it was almost as long. Did you find the process to be as pleasant, self-affirming, joyful and painless as I did?

EC: Oh yes. Just like for you. Absolutely. It’s just so joyful to be a writer. I’m bursting with joy and with things to say about how wonderful it is.

KB: Me too! You know in the movies, how, when they’re trying to show someone’s a writer, they show them sitting by a sunny window at their computer, smiling wistfully as a brilliant idea occurs to them and then they type, type, type away with a big grin…that’s just exactly what it’s like, right?

EC: Right. Right. No, it’s agony, as you know. Making something from nothing. Trying to embed something. Trying to have somebody do something. I don’t know why it’s so hard, but it is—to remain inventive, to remain energetic, to not succumb to despondency… I think every decent writer feels that. If you’re a happy person, why would you write? I kind of feel the same way about reading. Reading most good books is like entering into the pain of another, into the torture of another’s mind, which is cathartic, to feel someone else’s suffering for a change.

KB: Well, good. Speaking of suffering…I want to focus this conversation around the theme of darkness, darkness in writing.

EC: Of course you do, because you’re a dark writer. You’re one of the darkest writers I’ve ever taught.

KB: Oh, jeez.

EC: Which is fantastic. I love that. There’s not enough darkness in writing.

KB: Well, I agree. For me personally, having you as a teacher was very important because you were the first person to look at my writing and suggest that this interest I have in the darker side of relationships, psychology, history, human nature and experience, that this orientation I have could actually be an asset in writing, that it was okay to write darkly, to embrace that sensibility.

EC: Of course it is. Because I think you have to take the long view. In my mind, the darker writers are the writers who last. I mean they may not be the bestsellers in their lifetimes but theirs are the books that stretch beyond a generation. I think of the Russians. I’m thinking of a lot of the great American novels that are much about pain and longing and being an outsider, books like “Winesburg, Ohio,” “The Day of the Locusts,” “Miss Lonelyhearts,” the “The Death of Ivan Ilyich.”

KB: Oh god, “The Death of Ivan Ilyich.” I can still remember reading that for the first time in your novella class, what, twelve years ago? I was living in this apartment on Dubuque St. a block-and-a-half from the Dey House where workshop was held, and I read it lying on this musty couch that smelled like onions, and when I was done it took every ounce of willpower to get myself off the couch and go to workshop. I thought I might never be able to stand. The book was a weight on my chest, but also one of the most amazing works of short fiction I’ve ever read. Astounding but also crushingly dark.

EC: Yes, everyone’s waiting for the guy to die….and no one cares, and everyone’s like, well, there’s gonna be a job opening up…

KB: It’s true. This guy is suffering. He’s in so much pain and he’s so alone and the people who are supposed to love him don’t love him; they don’t care about him. They don’t give a shit, but then from that incredible darkness there’s this pinpoint of light at the end that’s almost blinding… Do you remember? His servant boy comes and holds his feet and just extends some human empathy, and that’s enough. He’s able to have compassion for his wife and his son and he dies and sees it as an act of compassion for them.

EC: Maybe that was Tolstoy blinking.

KB: Jesus… You’re not going to let me have it, are you?

EC: It’s hard to imagine that Tolstoy was thinking about his sales, but he probably was.

KB: You’re saying Tolstoy was worrying about Oprah, about how to get the book on Oprah? Well, he had no chance. I really feel that books like that are in such stark opposition to our culture, our desire to make everything we read about hope and affirmation. We want the books we read to make us feel better, which is a brand of bullshit that offends me deeply? I mean, yoga should make you feel better. Or beer. Or sex. Or some delicious food. But literature and art isn’t supposed to make you feel better, right?

EC: Well, paradoxically it makes you feel better by running you through the depth.

KB: Of course. But it’s not reaffirming in any simple way. It’s, as Chekov said, the correct presentation of the problem. It’s not supposed to offer a solution.

EC: But it’s hard to oppose that pressure. Did you blink away from the darkness in your writing of “The Houseguest?” Or did you ride it through?

KB: Well the book engages a very dark subject matter, certainly. There’s one thing that happens that’s pretty dark, and my editor did want me to make it more ambiguous, and he didn’t say it’s because it was too dark, but now that I think about it… of course, I’m sure that was a part of it. But I want to ask you… You’re writing for a very broad audience… Can you talk about how this tension has played out in your own writing? Your own desire to confront darkness, to grapple with it, but also not to completely lose your audience.

EC: Well, as much as I’m fascinated by it, I don’t think of myself as a relentlessly dark person. I think of myself as someone who I suspect, like John Cheever, suffers from moments of despair and also bouts of mania. Cheever was sort of a privately miserable man. A hidden man, desperate in a lot of ways. And I feel that way. That’s been my experience in life. But I think that’s where a lot of writers are. They have that deep feeling of bleakness but they’re also susceptible to illusions of delight. And in some ways that’s the tension that causes one to write. You can’t be gloomy and write. I think you have to be a little manic to actually sit down and force yourself to write 80,000 words and convince yourself that anyone’s going to care. To work it and work it and work it until it’s done. That’s a manic endeavor. But what you’re writing about often is intractably sad. In my own book, I really wanted to stay with the suffering for a while…but it doesn’t end on that, it ends on something else.

KB: You know, one of the things I do love about your work is the same thing I love about Cheever’s stories…. that you both write about the darker side of family life, about characters who often hurt, betray, and disappoint the people they love. Which is funny because you have such a perfect family.

EC: So it looks. Hahaha

KB: So it looks. Yes, but…

EC: And of course, by the way, there is no happy family that exists. There’s immense private suffering everywhere you look…Every single house on your block is full of private suffering. It’s got to be.

KB: Why is that? Why are we all so miserable?

EC: Because life is hard. You know, life in a lot of ways is difficult. It’s hard when you’re alone. It’s impossibly hard when you have five other people to live with, five variables. It’s hard to be married to the same person for a long time. It’s hard to be married to different people. It’s hard not to be married. It’s hard to deal with the difficulties your kids are having. I mean there’s illness, there’s death. In a way it’s kind of a miracle that we’re ever happy at all. Luckily we can occasionally feel the wind in our hair and the sunlight on our face. But it’s hard.

KB: I’m about to say, yeah, life is hard even for us as privileged, white Americans who have so much, but maybe— I don’t know. It’s like our privilege doesn’t seem to help with our happiness. We’re still so disconnected. I mean, I suppose we’re happier that we have clean drinking water and heat and our basic needs are being met and no one’s surrounding our fort getting ready to come pillage and rape and kill us…

EC: Yet.

KB: Right. Yet. But. But everything else beyond our basic needs being met, I mean, it doesn’t make us happy. Like all the shit that we have.

EC: No of course not. I mean, the pursuit of happiness. What is that? What the hell is that? It’s an outside construct, I don’t know what it is. Concentration for me is happiness. That’s the only time I really get any pleasure out of writing, if I’m enmeshed in it.

KB: Where you lose time?

EC: Yes. That’s like the definition of happiness, when time vanishes. And who knows, maybe it really is vanishing…Maybe…

KB: I feel the same way— concentration, losing time, and also feeling really connected to people. Sitting in a group, having great conversation with people you really care about. Those are really the only the things that bring me relief.

EC: And I’d add maybe intense physical exercise if you can get through the agonizing part.

KB: Oh, fuck no. I mean, whatever. It’s not on the same level as the other things.

EC: Sometimes I get it with music or movies or plays that are really good. You get this catharsis. I love what Kafka says… “Art is the pick that breaks apart the frozen sea of the soul.” In the modern world it’s so easy to feel constricted and compressed and driven to distraction by obligation… art is the only thing that cracks you open, that allows you to feel the world again. It places your problems in perspective. That’s one of the things that art does. It frees you.

KB: Why do you think that there’s so much resistance though to seeing that obvious pain that people have in themselves and in their relationships and in family life. We sentimentalize family life and parenthood. Parenthood is wonderful, it’s joyful. Hurray! We want to be perfect and beautiful and we get furious when people suggest it might be otherwise. It’s funny because people will watch TV or movies, things like “Game of Thrones,” shows about war and killing and rape and people’s heads being chopped off and the darkest, bleakest shit, and we love it. It’s very entertaining. But I feel like then when that dark gaze is turned inward, to our actual relationships, there’s incredible resistance to that.

EC: Isn’t that interesting? Well, I think artists go through two phases. They go through a phase of outward imagination like up to the midpoint of their lives. Their imagination focuses on what can happen, what can this character do… and then as they get older it becomes inward imagination. They begin to write about how one responds to the difficulties of situations, the internal struggle, to trust the depth of one’s experience. I mean, a lot of my students want to write about something that’s never been written before. The literary world sort of enforces that idea. Every piece of writing has to do something new. So they take out the quotation marks or write in a number of fonts or use endnotes and footnotes. That sort of thing… I don’t know. It’s not for me.

KB: You’re very traditional?

EC: Well, I’m traditional in the sense that… it’s enough. To write about the real experience of life, portrayed as closely as you can to actual life. It’s much more interesting to me than anything a writer can do with footnotes or fonts. I like books in which I become the character. I don’t like books in which the writer’s showing me how smart he is all the time. The smartest people I know speak a very simple language. That’s the tradition in the sciences, you know? That something’s right when it’s simple. And in the humanities it’s the reverse. People try to show their prowess by being complicated.

KB: I like things to be bold and inventive and surprising, but I like for that to come from within. I mean, say something radical about the world… something philosophical and emotional. That would interest me more than any stylistic flourish.

EC: Exactly, but see, you’re more like an older writer, even though you’re young.

KB: I’m old, Ethan. I’m feel very old. But okay, before I get any older, we need to talk about your book. I’m not going to ask you about math because I practically failed tenth-grade geometry.

EC: How could that be, Kim?

KB: I don’t know. It just is. I’m going to ask you instead about ambition, which is the other big theme in the book. It’s funny because this also seems like a cultural fixation, the valuation of ambition, the way we idealize it. It’s like, you can’t just do something. You have to do something and then take it to the next level. Monetize it. Professionalize it. This seems to be happening across the board with everything. It begins with children, with what we do to our kids. They can’t just take a dance class because it’s fun, they have to do it to progress, to excel and advance.

EC: Or even the fact that they’re taking a class. It used to be you just danced. Now everyone has to take a class. It used to be we just went out and played stick ball on the street. Now you have a coach from the Dominican Republic who has to come and work on your fielding before you even go out and play.

KB: When you’re five.

EC: I’ve never seen kids play soccer without a coach. I grew up every day of my life just playing stickball all day. A bunch of kids. Can’t do it anymore. It’s a terrible time to be a kid. A terrible time to be a kid.

KB: And a terrible time to be a parent. But this is my second book so we have to come back to this later. But you know, I do think even this has something to do with ambition. It’s not unrelated. Everything has to have a purpose. You don’t do anything just because it brings you joy. Everything is done to get you somewhere, to get you into the right school, to get you the right job, to get you into the next social class.

EC: I think it must stem from the worship of wealth, of material goods. I think it started with the dot com zillionaires in the nineties, where kids suddenly wanted to become wealthy, where that was their goal, to be a CEO or a company. And they didn’t feel ashamed of wanting that.

KB: Right, I mean no twenty-year-old in 1970 would have admitted to wanting to be a zillionaire CEO. But in all of these cases, though, ambition essentially stems from dissatisfaction, right? Agitation. Discontent. Ambition is the outward manifestation of an internal state of unrest. So the main character in your book, Milo Andret, is an extreme example of this state; this incredible ambition he has destroys him and the people he cares about. Do you think that fate is particular to this one character or do you think there’s a way in which all ambition, even less extreme examples, have a cost? Has there been a cost for you?”

EC: Certainly there’s been a cost for me. But—not to be too positive about things—but I wouldn’t have it any other way. As agitating as it is trying to do something bigger than yourself, it does give you a purpose without which life is just too scary to live. Obviously, it’s only a salve. Obviously, we all die. Obviously, there is no purpose to existence. But if you can’t find one or make one up, be it God or children or a novel, you know, god help you. It takes a great deal of calm to live without one of those supports.

KB: Yes, and that’s an issue of character, of fortitude or temperament. In your class, I remember a lot of your lessons were about character. You taught us things that seem obvious to me now but which were revelatory when I was hearing them from you—the idea, for example, that there are no villains in literature, that there are also no heroes. And that it’s always a very bad sign if a character seems either good or bad.… But there was one adjustment I’ve made to that over the years. Because for a while I would think, okay, no interesting character is good or bad, but it would paralyze me. Because I would write all these characters who were sort of like…meh… sort of ambivalent… not really compelling. So the mental adjustment I made is that now I think as I write, everyone is completely good and everyone is completely horrible depending on the moment at which you catch them. This is the case in my book, for example. That kind of complexity has always fascinated me, that people can be both awful and heroic. I think there’s a similar complexity at work in your book. Some people might call Milo Andret a monster. And I know what they mean. He does monstrous things. He hurts the people close to him in terrible ways. But you’ve said that you don’t see him as a monster.

EC: I see him as someone in incredible pain, as someone who fundamentally doesn’t trust the world. I feel pity for that, the inability to trust the love of others.

KB: Something that stays with me is a passage near the beginning of the novel. The narrator is describing how Milo grew up with his parents near Lake Michigan, within walking distance of the lake, but they never go on the lake because before Milo was born, his father fought in the Pacific and watched his fellow-soldiers eaten alive by sharks after their ship is torpedoed. It’s stated so matter of factly. And the narrator is speaking about one specific element of Milo’s childhood, not going in the water, but I think he’s really telling us so much more about that childhood, that family… that there was no joy, no love, no fun, no room for any of that, living in a home with a father so deeply traumatized. I mean, how are you supposed to be interested in fun when you come back from a war where you’ve watched people die and suffer in unspeakable ways.

EC: It’s true. You know, I was an adult the first time I heard someone say, “our family isn’t much interested in fun.”

KB: Who said that?

EC: A friend. It just struck me, such an odd statement. But as I got older, I realized that I’m not really all that interested in fun, either. Things other people find fun I don’t really find all that enjoyable.

KB: You mean like parasailing or something?

EC: Yes. Or big parties. I just don’t like that stuff.

KB: You find it as excruciating as I do?

EC: Yes. Or driving fast or skiing fast. I just don’t get it. I don’t want to go to the Oscars party. I don’t want to go to the big event. I get much more enjoyment out of solitude and contemplation and a good book.

KB: But see, the funny thing is, if you went to a writer’s colony or something, people like us who are deeply misanthropic and depressive, we’d become the life of that party, because I think that when you are that way and you meet someone else who’s like that, the joy of knowing that you’re not alone, you’re not the only wet blanket, is immense.

EC: Exactly. I was talking to an old friend of my wife’s. A very sweet guy who’d just gotten divorced. And I met him with another friend a week ago… and this other friend said to him, “Oh, I know this great woman you really need to meet. And he said, “I’d rather put my hand down the garbage disposal.”

KB: And there’s something so heartwarming about that, when you find another person who also finds the things that are supposed to be delightful, painful.

EC: Right, when you find a person who doesn’t say what you’re supposed to say. That’s what writing is, you know. Refusing to say what you’re supposed to say. In the Midwest especially there’s a lot of pressure not to do that, not to acknowledge anything unpleasant.

KB: I think it’s American…or America besides New York…And the problem is that positivity can be absolutely poisonous for the soul.

EC: Yes, it creates this pressure to normalize and to pretend these problems don’t exist. We’re now entering a period of flagrant positivity. And I wonder if that has something to do with everyone joining a corporation, majoring in what you’re supposed to major in, going to work for big companies. I was just visiting the Apple headquarters recently. And everyone’s working outdoors and playing on tight ropes and doing gymnastics and stuff, but you know, it’s still corporate culture. It’s still the man. They still own your soul. You’re still jockeying to rise.

KB: And corporate culture is the culture of positivity. You know, in my first workshop, you told me to read Mary Gaitskill because she wrote about sex and sexuality and relationships and family in such a dark and unflinching way. I was remembering that recently because I was editing an essay by this writer who was a dance major, and she was majoring in dance and trying to pay for her college tuition which was a hundred million dollars a year, and so she decided to work as an exotic dancer. So at first she worked at this place that was a local strip club and she was very sex-positive as they now say… she didn’t find it demeaning. There was a great group of women. Different body sizes. Different races. She wasn’t abused. The pay was okay. They had fun. It was a fun, sexy atmosphere. Then suddenly the place was bought out by this… stripping conglomerate or something, and she said it totally transformed everything and suddenly it was like she was working at Starbucks with her clothes off. She couldn’t be raunchy and dirty and hot and friendly. Everyone had to be positive and smile while they stripped and hawked calendars while giving lap dances. I read this and felt it was one of the scariest, darkest things I’d ever read about sex. But I don’t know…. it’s like, the things we think are scary: sex and feelings and desire… aren’t really scary. But the corporate stuff is scary, it’s fucking terrifying.

EC: And it’s scary to anyone with a sense of language, especially. Our kids… I have no problem with my kids swearing but I don’t want them using corporate language. People put words into your brain. That’s one of the hardest things about writing… figuring out what you actually think as opposed to what’s been put there, what’s received. And it’s a revelation. Someone saying what they’re not supposed to say, that they’d rather die then go to some party or they’d rather put their hand down the disposal than go on a date. The ability to think and to say what you actually think no matter how awful or dark it is.

KB: Exactly! And in places, in pockets, that ability to face it, to turn toward it, to not blink or recoil or pretend things are otherwise, that still exists. Maybe that’s the only thing there is to be positive about.

EC: Yes, yes. The untrammeled joy of negativity.

KB: Let’s drink to it. Is it too early to drink?