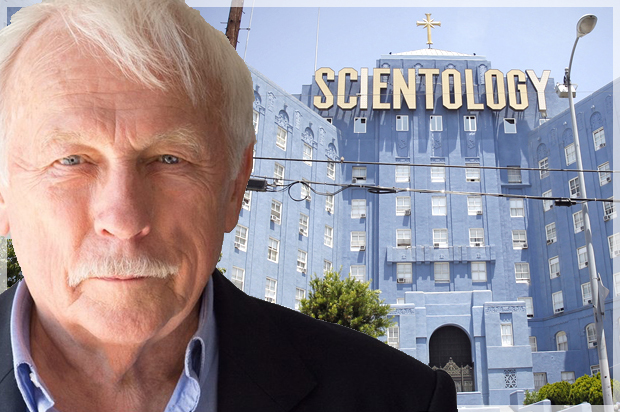

What’s it like to have a son drift away from you? What’s it like to be virtually imprisoned in an abusive facility? And what’s it like to see a religion you believed in turn into what you feel has become a nasty cult? Those all are things Ron Miscavige describes in his new book, “Ruthless: Scientology, My Son David Miscavige, and Me.” His tale is one of the most extreme examples of “disconnection” – the absolute breaking of ties between a Scientologist and a friend or family member — made even more extreme because the leader of Scientology is the son he raised in the church.

Except for a chilling prologue, the book starts innocently enough. Ron raises his four children, gets drawn into something that seems like a kind of self-help movement, and moves his family to a small town in England to get to know it better. According to his account, he gradually begins to see through the church at the same time he observes his son becoming vicious and calculating. Ron also describes escaping Gold Base – the church headquarters in the California desert – and leaving the church completely in 2012. Ron, who served in the Marine Corps and worked for decades as a professional jazz trumpeter, makes a likable narrator.

The book’s publication, however, has been met with protest from Scientology and David Miscavige — lawyers have sent letters to the book’s British and American publisher warning of a lawsuit for defamation. A statement from the Church calls the book “a sad exercise in betrayal” and claims that “Ronald Miscavige was nowhere around when David Miscavige ascended to the leadership of the Church of Scientology, mentored by and working directly with the religion’s founder L. Ron Hubbard, and entrusted by him with the future of the Church.”

Salon spoke to the Milwaukee-based writer from New York, where he was touring behind the book. The interview has been edited lightly for clarity.

It’s important to understand what the appeal of Scientology was for you and other people. What made you want to get involved with the church?

Years ago, I got involved with a multi-level marketing scheme called Holiday Magic. We had an opportunity meeting and there were some people there; one of them was a guy by the name of Mike Hess. He happened to mention to somebody that he was a Scientologist, and I heard this and I kind of pinned him down and said, “What is that?” I made him tell me about it for about 30, 40 minutes. It just interested me right off the bat. He told me of a Scientologist who used to have meetings at his cafeteria every Tuesday or Wednesday night and I started going to them. I found it interesting that you could apply some of this data on an everyday basis and it helped you, such as in communication or maybe interpersonal relationships, and that’s how I got interested.

How drastically has the church changed since you got involved?

It’s a 180. That’s how drastic it is. In ’69 and ’70, it was kind of very laissez-faire. You could go to an organization, referred to as “orgs,” and you’d go in there and find people were friendly; you could do courses that just were immediately helpful. It was like a self-help movement. It’s hard to explain how nice it was to go there. Everybody was there for the same purpose and you met a lot of friends, and it was reasonably priced.

Today, basically the prices are aimed at people who are very affluent or wealthy. It’s not accomplishing any of the purposes that I thought it was set out to do in the ’70s. In those days, what you were trying to make is “auditors.” An auditor is a person who counsels another person and brings them to a greater awareness of life and how they are, and maybe get over some of their failings and some of the things that upset them. These days, most of the emphasis is on raising money to buy new buildings, which is not the same as it was then.

Do you think the church should lose its tax-exempt status?

I don’t see how belonging to the Church of Scientology is going to do the same thing as just maybe a normal mainline religion like Catholicism or being a Protestant or whatever. Because the one thing that you’d find, I think, in people having a religion, is someplace where they can go and find some [solace] to some of the sufferings or the upsets they have in life.

I know with the Catholic Church, I was raised that way, they had confession. You could go tell a priest your sins and kind of get it off your chest and he’d give you some little penances to say and you’d do that and feel better. You go to Scientology and you go to a confessional and anything you say in there is recorded and written down. There’s a documented record of it and they will use that against you if you were to leave them or be critical of the church. The Catholic Church doesn’t do that. Scientology does it as a matter of course. Because of that, in [that] definition of a church I just don’t see how they can qualify.

Tell us about The Hole, which you describe in the book, and what kind of an effect it had on the environment.

The Hole was started as a “handling” to the marketing area of Scientology being reduced in effectiveness. L. Ron Hubbard said if management destroys or knocks out marketing, they should all be disbanded, taken off post, and marketing should be built up again. That’s the central marketing unit. That happened, and David took all those executives and put them into these trailers and that’s how The Hole started. They spent all day in there writing up their transgressions, or supposed transgressions, and questioning each other. They lived sequestered from the rest of the base. They would march down to our mess hall for their meals sequestered from the rest of the base. They’d go as a group and take a shower down in the garage.

It was like a little prison within the bigger prison of the base. Because the base itself turned into that, where you were sequestered from life. You usually couldn’t leave that place and go to a store or call on your own. You didn’t have cell phones; all of your phone calls went through an operator; people listened in on the calls; your mail was checked before it came in and before it went out. But The Hole was even lower than that, and these people were on their own, put in that place to kind of rehabilitate them as very bad sinners. It was destructive, as far as I’m concerned, to the people who lived there, because they became shells of their former selves.

When did you get the sense that your son was changing?

First of all, he was a terrific little kid. I’d get along with him great. A lovable little kid; he had a great sense of humor. We had a lot of fun together. When he joined the Sea Organization he was 16 years old. He really wanted to do that and I allowed him to do it because I felt if he wants to do this and this is his life’s purpose, why stop him? Because even prior to that he trained to be an auditor and he was a very good auditor.

Then I joined the Sea Organization about nine years later, and one day I’m at the base and I’m coming out of the music studio and I saw him walking with his entourage about 30 yards away from me. I shouted out, “Hey, Dave!” And he turned and gave me a look that I knew that I would never do that again. I then realized that I was not his father on that base, but I was another staff member. I think that particular moment was when I sensed there’s something that’s gone different than prior in his life with his relationship with me. I firmly believe the statement that Lord Acton made, that “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” I guess it turned out I was right, because the more power he got, the more alienated he became to me, as a father-son relationship. As a matter of fact, on the base, he never referred to me as “Dad;” he called me “Ron.”

And you started to hear and see things that he was doing to the whole base; it wasn’t just his relationship with you.

Oh yeah. We had a torrential rainstorm that had a mudslide and it almost crushed these buildings, and he took us into our eating area, which was a big hall, and for 30 minutes just said that it was [the staff] that caused that to happen. Not an act of God, but it was our bad wishes and our bad thoughts, and we were just a nothing after that point. That was in the ’90s and we never recovered from that. That day stands out in my mind as a day that I didn’t think things would ever change for the better after that. As it turned out, I was right.

You’ve described David developing a whole range of antisocial tendencies.

One of them is not caring for another person. That’s almost like you have no conscience. You can just do something to somebody and just walk away and you’ve done it.

I’ll give you an example. We were on the Freewinds, which is the ship that Scientology has for their uppermost level, and we had a performer there who said something onstage that he shouldn’t have said and it embarrassed David. The band was sent to the bilges as a punishment. The bilges in a ship, the temperature down there is between 125 and maybe 135 degrees. I was in my 60s, and prior to this I had somewhat of a heart condition, and he knew this but I had to go down there with the rest of the guys in that heat. It was inhuman as far as I’m concerned.

There are a lot of examples like that in your book of people being punished in harsh ways.

Oh yeah, absolutely. There’s just no concern for the person. Yet they will say that it’s totally the opposite, that he’s a kind and compassionate person, which just couldn’t be further from the truth. I personally know people who he punched, like Mark Fisher, like Tom De Vocht… I’m not going anonymous on any of these guys. There’s their names. They’ll go on camera and tell you what happened. Yet when it comes to anybody in the church who’s an official making their presence known and going on camera and being interviewed, they won’t do it.

Was this book painful for you to write? To recount all of these painful events and have your son drift away from you must be really hard to take.

You know the story about the PI’s, when they saw me grabbing my chest? Thought I was going to have a heart attack and they called… A few minutes later, David, or a person who identified himself as David Miscavige, got on and said, “Listen, if it’s his time to die, let him die. Don’t intervene. Don’t do anything.”

Even after I heard that—which was very painful for me, devastating as a father; I changed his diapers when he was a kid for Christ’s sake—even with that, I wasn’t going to do anything. I figured, alright, let me get in communication with him, and I called and I couldn’t talk to him. An attorney for the church got on the phone and said to me, “David won’t talk to you because he doesn’t feel he can trust you.”

He said that to me. After two PI’s getting paid $10,000 a week followed me around for a year and a half recording everything I did from eight o’clock in the morning to eight o’clock at night. That’s the convoluted type of thinking that goes on. But I said, “OK, then just tell him, ‘Don’t have people follow me anymore.’ I don’t like it, and just don’t do it.” I was going to let it slide.

So then I took the opportunity to go down to Florida with my wife in October of 2014 to talk to my daughters and see if I could repair the relationship, because by then they had stopped talking to me. So I went to my daughter Denise’s home and her husband came to the door, Jerry, and I said I want to talk to Denise and he says, “Well you can’t talk to her, she’s not here.” But she probably was there. After about 20 minutes of tap dancing with me, I said, “Hey Jerry, what’s the story here? Are you through with us?” And he said, “Ron, Denise and I are through with you and Becky forever.” That was the moment I decided to write the book.

Yes, it was not easy to sit down and do it, but I felt I had an obligation to do it. Not just for myself, but for the hundreds of other people who have been the subject of disconnection. People who no longer talk to their children, who no longer talk to their parents, friends of decades no longer talk to them. I felt somebody had to do something about it and I knew that I could get pretty good attention because of who I was. That’s why I wrote the book.

Once I started it, it just rolled out of me. Because I didn’t sit down at a typewriter or a computer. I tried doing that, but my fingers couldn’t keep up with my thoughts. I tried voice to text, but you spend 90 percent of your time correcting the words. So I got together with this friend of mine, Dan Koon, and we sat down at my house and he asked me questions. That book is a spoken narration of what happened and he took the recording and he put it into book form. That’s how it happened.

Once I got into it I knew that I was doing the right thing. Not only for my own self, but for the sake of a lot of people that I felt it might help. Will it help? Will it end disconnection? I don’t know, but I’ll tell you this: I couldn’t not do anything after that conversation with Jerry saying that they were through with me forever.

Who is your favorite trumpeter?

[Laughs] That’s a good question and it’s easy for me to answer it. There were two of them. One was Doc Severinsen and the other one was Louis Armstrong.