You may have seen the headlines this week.

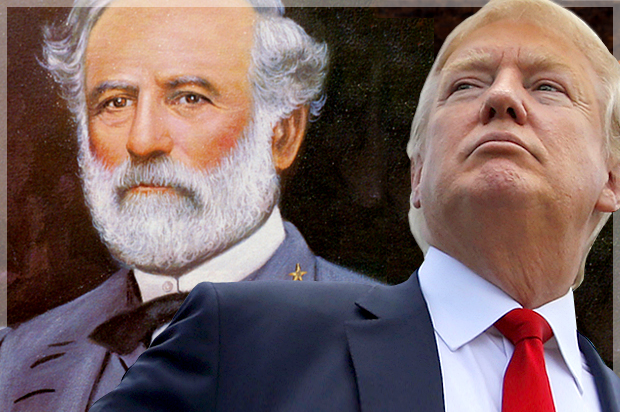

“Trump, Hitler, Schooly McSchoolerson in running for renaming Robert E. Lee Elementary”

“Of course Schoolie McSchoolface is a suggested name for a school”

“Boaty McBoatface, meet Donald J. Trump, er, or Adolf Hitler Elementary School”

In Austin, Texas, the School Board solicited suggestions for new names for Robert E. Lee Elementary School, and it got hijacked by the internet. The suggestions included Adam Lanza Elementary, Bleeding Heart Liberal Elementary, and worse.

As it happens the school-soon-to-be-formerly-known-as-Robert E. Lee Elementary is where my kids go. More than that. My wife and I have been involved from the start in the effort to change the name. So it’s been a surreal and disturbing week.

The headlines seem to suggest either that our community is really so backward it endorses such suggestions or that the work the parents have done is so politically correct and hypersensitive it deserves this kind of treatment.

The truth is less sensational. We are ordinary parents who have been struggling with a classically American question in a very traditional, democratic-minded way: What kind of school do we want for our kids?

The real story begins last summer, after the horrific shooting in Charleston. Jessica and I, along with a small group of parents, began organizing to change the name of our Austin, Texas school.

It wasn’t a novel idea. In fact, it’s been broached many times over the last couple of decades. Even for Austin our neighborhood is a deep blue zone. It’s close to the University of Texas campus, and the community of parents includes writers, professors, artists, musicians, and a lot of transplants from the northeast and the west coast.

It’s also a very white neighborhood, and a very white school. In part this is a consequence of standard demographic patterns of money, race, and inequality. In the case of Austin it’s also the consequence of very deliberate policies of segregation, dating back to before the school was built in 1939, and persisting for decades after. These policies have left a clear and living imprint on what kinds of people live where in Austin today.

The school name, which was chosen in 1939 at the suggestion of the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, was a reflection of the character and ideology of the neighborhood in the 1930s. In 2016 it’s an active deterrent to black families in Austin to move to the neighborhood, and it honors a narrative of southern history that we believe is false and toxic.

It’s been an open wound for a while. Until the shooting last year, however, and the national conversation it provoked about the persistent Southern celebration of confederate heroes and icons, the occasional complaints hadn’t gotten much traction.

This time was different. We started out with about eight of us. We began meeting with School Board members. We started a Change.org petition. A few of us wrote op-eds in the local newspaper. We spoke at public meetings. Our numbers grew. The School Board decided to take up the issue, and began investigating what would need to happen for the school name to be changed. Local media began showing up outside the school and wanting to interview us. Our numbers grew some more.

It’s been a slow, often frustratingly bureaucratic process. Meetings after meetings. School Board rules that have had to be amended. There was a counter-petition on Change.org, and a group of people who began organizing in opposition to the idea of changing the name. The historic commission got involved, and there were questions about whether or not the art deco lettering on the school’s facade was protected.

As we went our arguments acquired depth and subtlety in response to criticism. We took on the question of whether we were trying to erase history. We asked ourselves, very directly and candidly, whether we were being precious, whether this was a purely symbolic effort to expiate our white guilt, or preen self-righteously before the public.

We decided not that we were pure, or that our motives were uncomplicated, but that we have a right to influence who and what our kids’ school honors. This is about our values, and about the message we are sending to students of color and their parents. It is also about correcting, not erasing, a sentimental, factually inaccurate, and politically toxic historical narrative of the South and the Civil War. We decided we could do better.

And we did. On March 28 the Austin Independent School District Board voted 8-0, with one absention, to change the name of Robert E. Lee Elementary School.

I don’t want to dive back into the arguments we made that won the day. You can read what we and others have said elsewhere. If you’re inclined to disagree, I doubt anything I’d say right now will change your mind. And it’s over. The name will be changed to something thoughtful and meaningful, suggested by the school community and selected by the School Board. (The online form was only to solicit suggestions; it was never a vote.)

What I would hope to persuade you, whatever your feelings on the issue, is that we’ve been mischaracterized. It’s right there in some of the names that were suggested, like Hypothetical Perfect Person Memorial Elementary School, Bleeding Heart Liberal Elementary. The idea is that we’re frivolous, that somehow this isn’t serious, substantive politics.

The rejoinder to that is the history to which we’re responding. It’s the decades of work, by groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, to populate the south with monuments to the Confederacy. These were people who believed that it was profoundly important to make sure that their kids’ schools, among other institutions, were named after Confederate heroes. They fought for it. They spoke at meetings. They organized with other parents. Sometimes they faced opposition. Sometimes they didn’t (I looked in the minutes of the Austin School Board in 1939 — no one had any objection to naming the school after Robert E. Lee).

These were real people. Passionate about their history and their politics, committed to creating a world for their children that honored their values.

It’s easy to lose sight of the actual people-ness of distant, anonymous people. It’s easy when they lived decades ago, and had values that you find abhorrent (as I find those old neo-Confederate values). And it’s easy when your only sense of people comes from sensationalized headlines and quick-take tweets.

There’s a cost to the dehumanization. It makes the whole process seem like a goof, and it hasn’t been. It wasn’t 75 years ago, and it isn’t now. It’s our school, our kids, our hallways, our lives.

We didn’t do any of this lightly. You’d know this instantly if you spent even five minutes on any given morning, at around 7:45 a.m., watching us drop off our kids, hugging and kissing them goodbye. You’d know it if you saw the tense moments, in the hallway, when parents on opposite sides of the issue pass each other. You’d know if it you saw how much we support and sustain the school, in a million little ways, every day. You’d know it if you spent a few minutes in the shoes of our principal, who’s handled all this craziness, in his second year on the job, with admirable patience and judgement.

Recognizing our basic humanity and good faith matters, I think, because while Hypothetical Perfect Person Memorial Elementary School is pretty funny, and Schooly McSchoolerson is a little bit funny, Adolf Hitler Elementary School actually isn’t. Adam Lanza Elementary School isn’t. And I’d wager it was the ability to lose sight of our basic humanity, in the first place, that enabled anonymous form-submitters to propose these really gruesome names.

It’s a losing battle, maybe, to push back against the ways in which mass media, and the mass nature of modern life, enable us to dehumanize other people. But it’s one worth fighting. Because it’s not just silly internet kerfuffles that happen when we dehumanize, it’s all the worst aspects of human nature and politics.

It doesn’t take much to imagine distant, anonymous people as caricatures. It takes more, but really not that much more–maybe a few seconds more–to imagine us as flesh and blood people, who love our kids, care about our school, and have fought to change it’s name because it’s important to us.