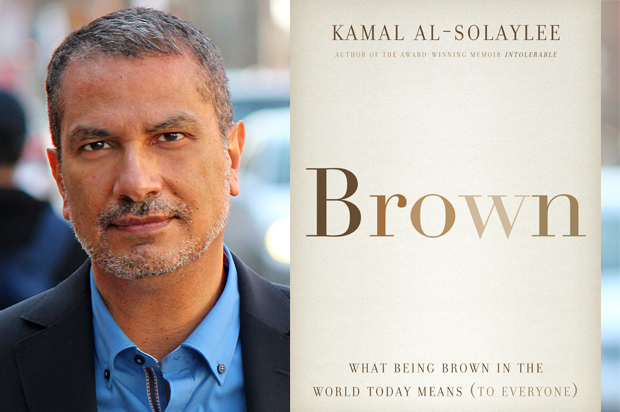

Toronto-based writer Kamal Al-Solaylee’s first book, “Intolerable” (2012), recounted his harrowing youth as a gay Yemeni coming of age in the Middle East. In the book, the author — once a theatre critic for the Globe and Mail and now a journalism professor at Ryerson University — artfully melded the personal and political into a powerful memoir.

Al-Solaylee takes this approach even further in his follow-up, “Brown: What Being Brown Means in the World Today (To Everyone)” (HarperCollins Canada, May 10). The book is a far-reaching analysis of what it means to have brown skin in the world, beginning with the author’s own realization of his skin color. In an agonizing childhood moment of self-hatred, he realizes he is brown-skinned when faced with the blinding whiteness of the child actor playing the lead role in the British musical “Oliver!”

Al-Solaylee then takes us on a global tour, where being brown means a variety of things. He interviews service workers in the Philippines, surveys the Arab diaspora in Britain, chronicles the struggles of undocumented Latino workers in America, and finds that Canada has its own flaws. (An analysis of the October federal election, in which former Prime Minister Stephen Harper attempted to leverage fear of Muslims as an election wedge issue, is included.)

It speaks to Al-Solaylee’s talent as a writer that “Brown” pulls us into its multiple worlds of multiple identities, providing a unique portrait of a group of people who often provide vital labour but are just as often invisible. It’s a masterful fusion of Al-Solaylee’s own observations, anecdotes from his interview subjects and analysis of data and statistics. Indeed, “Brown” reads almost like an identity-politics thriller, as vivid as it is informative; about a third of the way through it, you realize you’re reading one of those important books that will stay with you long after you’ve put it down.

Al-Solaylee spoke to Salon about his inspiration for the book and the process of writing “Brown.”

“Brown” is full of big ideas and really quite epic in scope. What inspired it?

The book came at me from so many different directions. Its starting point was very personal: being a brown man in the post-9/11 world where my skin tones and Arabic name make me guilty by association of terrorism or people who might be terrorists. But I also recall thinking that everywhere I go the service and low-paid jobs are increasingly performed by brown migrant workers. I was in Hong Kong in 2011 when I saw for the first time thousands of Filipino domestic workers enjoying picnics on Sundays, their only day off. And a few years earlier, I remember being on the bus that travels through Rosedale, one of Toronto’s loftiest neighborhoods, and the only passengers with me were also domestic workers and nannies. I got the idea that brown is the color of cheap and exploited labor. I thought there might be a premise to explore in a book there.

How did you decide which places to explore?

That came down to a combination of what stories I wanted to tell; how many contacts, if any, I had in each destination; and who got back to my email or phone inquiries with a genuine offer to help. It was vital to have contacts in each country before arriving. I didn’t have a huge budget to travel or as much time as I would have liked, so I had to do a lot of pre-planning and pre-book as many interviews each day as humanly possible. That said, I was let down more than once by contacts who promised to help but avoided me once I arrived. For Doha, Qatar, my contact never returned any of my emails after I booked my ticket. I had to improvise.

Was it difficult to secure interview subjects?

It varied from place to place. I was disappointed but not surprised at how many people in the U.K. and Canada were reluctant to talk about the scapegoating of Muslims in their respective contexts. I do think the politics of David Cameron and Stephen Harper have forced many Arabs and Muslims to be suspicious of fellow brown people who ask too many questions. It’s a form of self-censorship or of internalizing years of being cast as the enemy of western values. I found workers from Sri Lanka, the Philippines or Indonesia more willing to talk openly. They want someone to tell their stories, take up their cases. I was aware that I couldn’t include every story I heard and felt the usual pangs of guilt at the possibility of taking advantage of sources to write my book. I think I manage it but others may disagree.

Amid all the research, what was the most painful revelation for you?

On one level, the book confirmed what I always suspected — and heard on the cast album of “Avenue Q”: Everyone IS “a little bit racist.” Black people, brown people, East Asians, whites — there’s no monopoly on race-based prejudice. But perhaps I wasn’t prepared for the specific hatred and antagonism that immigrants and long-term residents of North African descent experience in France. I visited Paris a few months after the Charlie Hebdo murders — but before the November 13 attacks — and could feel the tension between white and brown France in the air.

The word intersectional is gaining a lot of traction in academic and activist circles lately. Your book makes these connections in such a clear, lucid way.

I have to be honest and say that I didn’t know what intersectionality meant exactly until a student brought it up in class after I finished the first draft. I Googled it right away. I wasn’t conscious of doing it, but the connections between race and economics, gender division of labour, migration and sexuality and desire just forced their way into everything I was researching or reporting on. How do you separate the situation of domestic workers from the Philippines in a place like Hong Kong without tracing the economic development of the latter from a manufacturing into a service economy in the 1970s? That helped local women enter the workforce in the thousands and gave them the option to “outsource” child and elderly care to brown workers from poorer countries.

Your first book was very much about coming of age as a gay man. Did your known gay identity pose any problems while conducting your research?

I’m good at going back into the closet in countries or situations where my safety or my life might be in danger – as I do when I go back to the Middle East, for example. It’s a survival mechanism. I was apprehensive about travelling to Qatar, not because of my sexuality but because of the government’s record of harassing or silencing journalists who write about the terrible conditions of migrant workers. But, thanks to my brown skin, I managed to blend in with the masses of brown workers around the Industrial Area. With one exception, no one stopped me or made feel like I didn’t belong. If I were a journalist of white, European background, I would have stood out. Advantage brown, I guess.

You conclude by discussing how the Harper government tried to use fear of the brown other as a wedge issue in the Canadian election, but failed. Did the outcome of the election — in which the Liberals won by a landslide — leave you feeling more confident?

To be clear, the brown other in Canada was always the Muslim, and never any other Eastern religion. Hindus or Sikhs didn’t get targeted the way Muslims did. I do feel more confident now that the Liberals are in charge, but I also know that Party’s more conservative, hawkish wing needs to be watched. Although I doubt that anything will be as hateful as the Harper years. At least I hope not.

This is a book full of valuable research, but also a deeply personal book. What do you hope people will take away from reading “Brown?”

I really want them to think about the immigrant serving them coffee at their local Tim Hortons, driving their home in a cab or cleaning their office late at night. What’s their story? What kind of economic or political catastrophe has forced them out of their homeland and who have they left behind? No doubt, each story will be as unique as the person telling it, but collectively the different stories paint a bigger picture of failures in the Global South and tensions in the Industrialized North that’s the world in which we live. That’s not a lot to ask, is it?