Shortly after Donald Trump became the presumptive Republican nominee for president, a subgenre of “explain Trump” articles emerged, linking the “Trump phenomenon” to fundamental tensions within liberalism and liberal democracy. The pinnacle of the genre is Andrew Sullivan’s New York magazine piece, which argues that too much democracy has made the U.S. vulnerable to authoritarianism, thus a Trump presidency would be an “extinction-level event.” While I appreciate the complexity of circumstances that produce a nominee like Trump, I’m also concerned that we’re trying too hard to see Trump as the uniquely complex phenomenon that he isn’t.

Accordingly, this is not another attempt to explain how Trump went from joke candidate to likely Republican nominee, nor to theorize the contradictions within Western liberal democracy or contemporary U.S. liberal politics. This is simply a reminder of what Republican leaders were already saying when Trump was barely a blip on the political radar. This is an effort to point out that discussing Trump as if he’s the unique culmination of a grand narrative is like disowning your troubled son to forget how you raised him.

Consider the recent history of Mitt Romney’s presidential candidacy, for example. Romney centered his candidacy on the idea that he was an experienced and effective businessman, despite having also served a term as governor of Massachusetts. The Republican case for Romney was based largely on the idea that the U.S. needed a “lean and mean” business approach to reinvigorate the economy; that balancing the federal budget and managing the national debt are just like making personal finance decisions; that “Washington insider” politicians aren’t as effective at governing as business outsiders. Romney’s “corporations are people” line was a Kinsley gaffe because it illustrated too bluntly the Republican Party’s deliberate conflation of governance and management.

Indeed, one of the things bothering Andrew Sullivan about Trump, quite rightly, is that Trump is a total outsider with no experience in government. As Sullivan laments, “Once, candidates built a career through experience in elected or Cabinet positions or as military commanders; they were effectively selected by peer review. That elitist sorting mechanism has slowly imploded.”

Sullivan looks to a collapse of governmental peer-review to explain how one of two major parties could nominate for president someone who’s never served in any branch of government and appears to know next to nothing about governing. Fair enough. But it’s also the case that the Republican Party—and its less uncouth leaders, like Mitt Romney—have been telling us for many electoral cycles now that the fate of our country rests on electing an outsider with a business background. Surely that profile sounds familiar to those now reckoning with a Trump presidency and a plan to default on national debt, as if the U.S. were a business filing for bankruptcy.

In this vein of inquiry, I’m reminded also of Lindsey Graham, regarded throughout his career as a sensible, moderate, insider Republican. Almost exactly a year ago, well before Trump was a serious contender for the presidency, Graham was speaking at an AIPAC dinner and feeling out a possible 2016 presidential run. “Al Qaeda, Al Nusra, Al Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula,” riffed Graham, “Everything that starts with ‘Al’ [‘the’] in the Middle East is bad news.” Arab and Muslim baiting were prominent facets of the GOP presidential primary in the 2012 election cycle, too; and by 2014 a majority of polled Republicans held negative views of Islam. Trump is inelegant, but so was Graham last year at AIPAC; and both of them are communicating anti-Arab and anti-Islamic sentiments to which Republican audiences were receptive before Trump took the party’s center stage.

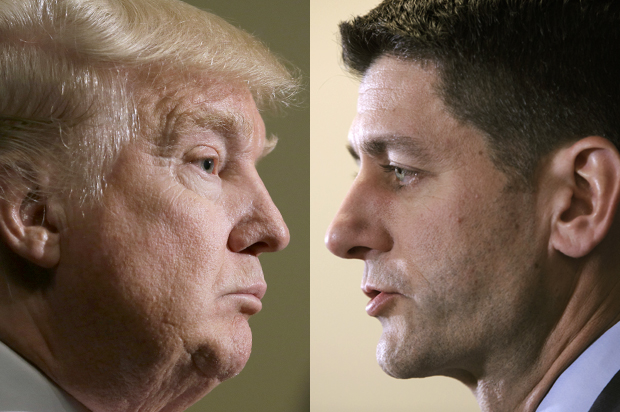

Whether we look at immigration reform, like the time acceptable Republican politician Marco Rubio used “amnesty” as if it were a dirty word; or opposing equal pay for women, like Mitt Romney’s “binders full of women” episode; or the #BlackLivesMatter movement, which Chris Christie equates with justifying the killing of police officers; or poverty, which Speaker of the House Paul Ryan explains with racist dog whistles about lazy “inner city men”; it’s clear that nothing about what Trump says is unique, not even the way he says it.

Note that I’ve drawn these examples of Trumpish politics from key Republican politicians elected to major offices, most of whom have also been presidential candidates. To this point I’ve left out what we mistakenly refer to as “fringe” Republicans like Louis Gohmert, who claims the U.S. is worse off now than during slavery; or Steve King, who infamously envisioned Mexicans with “calves the size of cantaloupes because they’re hauling seventy-five pounds of marijuana across the desert.” Until now, I haven’t mentioned Sarah Palin, who, among other things, invented a nativist crisis in a call to Latinos to “speak American.” And I won’t mention by name anyone who’s promulgated Trumpish views on TV or radio. But it’s easy to forget that these “fringe” operatives who have long spoken Trump more than they’ve spoken “American” hold or have held major national offices (Palin, of course, was not so far off from the presidency as Trump presently is).

So when Republican operatives like Max Boot declare pathetically (I use the word in the classical sense) “The Republican party is dead,” and that Trump is standing over the body, what makes such declarations pathetic (now in the colloquial sense) is how obviously the death of the Republican Party—such as it is—was an inside job. Looking back to Romney and Rubio as if they represent a golden age when one didn’t have to express antipathy toward Muslims, immigrants, women and “insider” politicians to secure the Republican nomination for president is the height of cognitive dissonance.

As we face down the possibility of a Trump presidency, then, we need to resist the desire to romanticize Trump as a special snowflake and a pivotal event. This is only a pivotal moment insofar as we’ve squandered or ignored so many prior opportunities to pivot before we got here. “Extinction-level event” is a provocative way of seeing things, but extinction is also a gradual process.