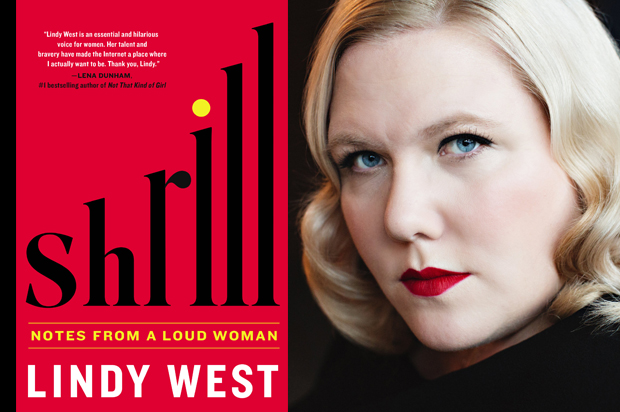

Lindy West did not set out to be a feminist warrior against the forces that wish to silence and hurt women for doing things that men take for granted, like expressing opinions or having ordinary interests like stand-up comedy. As she details in her new memoir, “Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman”, she actually started out life as a shy kid and an aspiring writer, and came into her adult life as an outspoken public figure with an F-you attitude out of a sense of necessity.

Someone has to fight the misogynists, after all, and West is well-situated for the front lines, lacing her blunt sense of humor with a surprising amount of nuanced empathy, even for those out there who are the ugliest to women. I interviewed West about her new book, her unwanted second career of handling haters, and what it takes to fight for self-esteem in a society that so frequently wants to deny it to women.

You’ve titled your book “Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman,” and I’m sure you’re getting pushback for that from people who think the title is confrontational. Why did you and your publisher decide to go with that title?

It’s funny, there wasn’t a ton of discussion about it. Actually, my husband came up with it a long time ago, when I was still in the early stages of working on the proposal. We were both like “Huh,” because I think some troll had called me shrill and he was like, “That would be a good title for your book.” And then we were like, “Yeah, that would be a good title for my book.”

So it was just the working title, and I don’t think anyone at my publisher ever even mentioned it. We just sort of moved ahead with it. It encapsulates a lot of complex, nuanced concepts in just one word, in terms of the double-standards of how we talk about women and how we talk about men; how we use arbitrary notions like women’s “tone,” which is essentially an aesthetic standard in line with all the other ways we confine women using aesthetics, to discredit women’s ideas, which is not something we do to men.

Unless you count the Dean scream, which is the closest thing I can think of.

It communicates the idea of reclaiming words that are used against us, which is hugely important in social justice movements. I knew it was going to be coming out in an election year and Hillary was going to be running and I knew that that idea was going to be on people’s minds and there would be opportunities to thinkpiece about it.

The word shrill is interesting to me because I get called that all the time, in response to my writing. I can’t help but wonder, how would you know what tone of voice I “said” that in. I typed it.

I have some critiques of my own voice, like everyone does because it’s horrible to have to hear your own voice, but none of them are “shrill.” That’s not my problem. I have like a weird low voice. [Laughs] Shrill is not my problem.

I pretty much exclusively get it in print. So obviously it’s not about sound anyway. It’s about message, but they pretend it’s about sound.

You spend a lot of time in the book talking about some conflicts that you’ve had with people that have tried to police and silence you over a variety of issues, including feminism, fat activism, and anti-rape activism. Has that been a common theme? This notion that your female-ness is a reason you should be quiet.

Yeah, I certainly have felt that way. I didn’t realize until I was in my late 20s that that was the paradigm that I was existing inside of. You’re not aware of it when you grow up in it. It just felt natural. But then I started to change my thinking on some of those issues and stop being afraid to talk about my body and to talk about feminism and to confront the gender-bias in some of these worlds that are really important to me. Particularly in the book, I talk about comedy a lot and the way that misogyny affects women in comedy.

So once I started to push through this fear of talking about those things, I realized that I had been afraid because there was a system in place trying to make me afraid, as a self-preservation mechanism. Once I started being loud and honest about those issues and getting this degree of pushback, it affirmed the need for me to speak out more. It was self-perpetuating.

When I started to push against my natural instinct to be shy and quiet and small, and people reacted with such shrieking vitriol, it was like, oh, there’s a thing here. It helped me see something I hadn’t consciously understood before.

You’ve done a lot of stand-up comedy and you have a couple of chapters in the book where you talk about what it’s like to love a community that doesn’t love you back, as a woman. Can you talk some more about that?

It’s really demoralizing if you look directly at it and you let yourself see how cruel this community you love is being to you. Some of the shittiest comments I get when I do comedy are from women who have sort of adopted this “cool girl” persona where it’s really performative and they want to show the men in their communities that they’re not that kind of girl comic, they’re the cool kind of girl comic who doesn’t complain and laughs along with misogynist jokes and thinks rape is hilarious.

I empathize with that. It’s scary to think about being rejected by a community that means everything to you. I get it. It’s almost the same impulse as the men who harassed me for critiquing, say, “Opie & Anthony”. They’re afraid that the mean feminist is going to ruin their radio show club, because they need that club. I know that it feels like a family because I’ve been a part of a community like that.

But what they don’t understand—or they do understand, because it’s explicit a lot of times— is that their comfort comes at the expense of women’s comfort and safety and full humanity. It’s scary to push back against that and to complain because then you get ostracized.

It’s a trap. The reason you want to speak up is because you love this thing so much, and by speaking up you get kicked out. I’m really happy to have been able to contribute in whatever way I have to making the comedy community at least a little more receptive to hearing women’s experiences, which I think has opened up over the past five years or so.

When I first started writing about comedy—which I could do because I’m not trying to be a comic; I don’t have to get stage time or be on good terms with comedy club owners or bookers, so I was in a realistic spot to complain—I would get emails all the time from female comics saying, “Thank you for saying this. I can’t speak up because I’ll never get booked on a show again.” Because you get branded as a troublemaker, you’re not cool.

Now I’m a member of a couple different private Facebook groups of female comics and women in comedy in general, writers and bookers and promoters, who have started to create these spaces to share stories and warn each other about men in the community who might be unsafe or clubs where they had bad experiences or just to discuss what they’re going through and support each other. It’s really heartening and cool.

You write in the book about “coming out as fat,” which you write about as a process rather than something that’s self-evident. Why did you make that distinction?

We’re trained to see fat people as like thin people who are currently failing, as broken thin people and not as something that just exists. And you’re trained to see yourself like that.

That’s how the diet industry works: “You’re not a fat person, you’re a failed thin person.” That makes it really hard to advocate for yourself. You just live in the future and not the present, and you won’t admit to yourself or to the people around you that this is who you are and what your body looks like now—even if your body is going to change later, and it sometimes does.

But this idea that you’re a work in progress is in the rhetoric everywhere: That Oprah is a thin woman trapped in fat woman’s body or whatever it was she said in her commercial. That we’re all just thin people inside, and some of us just do a bad job, but will somehow excavate our real bodies. It’s really alienating. It really separates you from your body in a way that I find kind of scary.

Because if no one identifies as a fat person and we’re all just “before” pictures, then how can you say that fat people are even real? It’s stigmatizing. It’s a really effective mechanism for keeping fat people from advocating for themselves and from teaching thin people to have empathy and respect for the fat people around them, who are just human beings and might get fatter and never be thin.

That was my greatest fear when I was in my early 20s. I realized one day, “Oh my God, this is going to be the struggle of my life. This is never going to go away and I might never be thin.”

And that had never occurred to me before. I always thought, “OK. Tomorrow. This time it’s gonna work, and then I’ll be my real self and my life will start.”

And that’s just a horrible way to live your life, because it’s not living your life, it’s waiting to live your life and in the meantime just punishing yourself every day for nothing.