Andi Zeisler is one of the founding editors of Bitch magazine, a 20-year-old feminist publication that was started and continues to this day to be an examination of feminism and pop culture. For a long time, Bitch was a fairly unique publication, but in the past decade, the internet has created an explosion of Bitch-style writing about feminism pop culture.

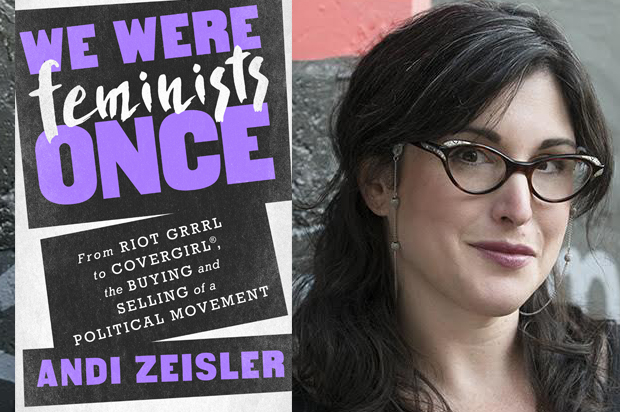

Just as interestingly, pop culture seems to be talking back. Feminism has gone mainstream, with pop stars adopting the term and movie stars pushing for equal pay for equal work. In her new book “We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl®, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement”, Zeisler takes a critical eye towards this pop culture embrace of feminism. It’s exciting in parts, troubling in parts and rarely, if ever, simple.

I spoke with Zeisler about her book, Taylor Swift and what feminism means in an era when it’s being used to pitch soap and make-up.

Feminism is having a moment in pop culture with stars like Beyoncé and Taylor Swift embracing the term publicly and multiple feminist campaigns going mainstream in a big way. I’ve personally been really excited about this, but in your book you argue that we should be skeptical of all this “rah-rah,” “you go girl” feminism. Why?

I should clarify by saying that I’m really excited too. That’s always been part of what Bitch’s mission is about, to really sort of locate feminism and opportunities to really make feminism important within mainstream culture. It’s not that I think it’s a bad thing inherently, it’s just that I’m sort of ambivalent about the way it’s manifesting in a lot of ways. The idea of marketplace feminism, which I define as a process by which the language and imagery that have been created and nurtured within feminist movements are sort of harnessed in the service of capitalism, I see that as definitely something that’s happening parallel to really grassroots and increasingly grassroots and intersectional and nuanced feminist campaigns. So it’s almost like there are these two realms and there’s not a ton of overlap between them and one is just being amplified much more than the other one. And I have concerns about that, because the one that is the loudest and the most eye-catching is also the more simplistic of them.

What would be a good example of the marketplace feminism that concerns you?

I think advertising and the realms in advertising where feminists concepts have sort of been harnessed. Things like the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty or the Always Throw Like a Girl campaign, where it’s always very loosely about the idea of empowerment and feeling good about yourself, but it’s also very much a canny kind of way to sell stuff. Instead of using the language of shame and insecurity, which has always been the mainstay of marketing to women, the language is kind of switched to be about this vague idea of empowerment and personal sense of well-being that comes from feeling good about yourself. But the products are not changing.

And certainly in the case of Dove, it hasn’t stopped the brand from continuing to invent new insecurities for women to address with Dove products, like their whitening underarm deodorant or whatever it is.

It’s a bait-and-switch, but it’s very clever and it’s often very well done. Especially with the use of viral videos, Dove has really managed to kind of hijack concepts about beauty and self-esteem and questioning beauty standards that have always existed within feminist movements.

An example that’s more in mainstream culture is Sheryl Sandberg and the whole Lean In movement and the idea that there’s this very individualized embrace of feminism as being about your own personal success, your own personal self-actualization, your own potential, but is not really about feminism as action and feminism as being about liberating all women.

There can be a reactionary vibe in these things. Willingly or not, they imply that the biggest obstacle for women between them and “empowerment” is themselves, not society.

Exactly, and that’s what’s so insidious about it. We’re already a society and a consumer culture that’s really focused almost exclusively on the individual, and so this kind of language really doubles down on that and makes it seem like we don’t have to be battling systems and reforming institutions and values within them, we just need to get over ourselves or feel empowered or own our inner warrior or whatever. It works very well for a capitalistic society, but it does not work very well if we’re talking about the larger project of equality and liberation and reform.

Speaking to your ambivalence, there are definitely examples that come to mind of pop culture feminism that come to mind that are just awesome and very powerful and send the right message. I’ve become mildly obsessed with Beyoncé’s “Lemonade,” and I think it’s a really good example of feminism in pop culture done right. What do you think of that?

I talk about Beyoncé quite a bit in the book because I feel like for the past several years she has been this incredibly divisive figure both among people who self-identify as feminists and people who don’t. There’s this very push-pull dynamic between people who, for whatever reason, want to claim that Beyoncé can’t be a feminist because she doesn’t wear pants or she’s married to Jay-Z or any number of things. Then there are people who think there has always been this thread of feminism running through her work — she contributed to the Shriver report, she really does think about feminism on an intersectional level. So it’s a really weird dynamic.

I have to say that I don’t really feel at all qualified to talk about “Lemonade” as a piece of art or social commentary, just because it’s so specifically for black women and about this place—both physically the place of the self and culturally the place of institutionalized racism and police brutality.

So I have avoided wading into that fray, but I think it’s an excellent example of why it’s very hard for people to accept Beyoncé as a feminist, because she does go beyond these kind of safe platitudes about empowerment and feeling good and feminism being about whatever it is you want it to be about. She really does challenge that frame, and that’s something we definitely don’t expect the biggest pop star in the world to do. It definitely is a way of expressing her power and her knowledge and her experience that makes a lot of people uncomfortable, I think.

One of the examples you use of why we should be more skeptical is that while all of this has been going on in the media, we’re also seeing in the real world a loss of rights for women. Particularly in red states, Republicans have been shutting down abortion clinics through red tape regulation at an astonishing rate. I sense that this is a backlash, because feminists are making progress and it’s causing conservatives to panic and put all their resources and energy into things like curtailing reproductive rights as a response. What do you think of that?

Yeah, I think that’s definitely true. I think partly because of the speed with which news and culture is mediated, there’s definitely been a condensing of backlash cycles, where we see them happening more and more concurrently as time goes on. This is partly why I wanted to write this book: to talk about the fact that embrace and backlash have always been things that really played out within the media and pop culture, and have really shaped how we publicly understand feminism and how feminist ideals get filtered through media and pop culture.

It’s tough, because it’s absolutely true that we have really seen feminism become so much more almost ambient, in the sense that there’s a lot that we just sort of naturally understand as crucial in a way that we didn’t even three or four decades ago. We understand that we’re not going to let someone like Bill Cosby slide anymore. We understand that there’s a level of transparency that when organizations like Susan G. Komen start talking about no longer funding Planned Parenthood for some bullshit reason, there’s gonna be a critical mass of pushback.

So yeah, a lot of what has happened has happened because there has been so much grassroots and often online-based feminist action. But at the same time, there’s a little bit of a danger in feeling like we have come to a certain place and can or should be satisfied with what’s happening. Because as we’ve seen in many parts of history, you can’t stop, because there’s always a backlash that’s either right around the corner or already happening. And again, this is why I do feel ambivalent. This is why I don’t feel like this is a really cut-and-dried situation of “pop culture feminism is bad” or “pop culture feminism is amazing.” I think it’s both at once.

Besides Beyoncé, who are some examples of people you think are getting it right?

Someone was asking me about Amy Schumer recently, and I have to say I like Amy Schumer and I think she does get it right. I mean, no one is gonna get it right all the time, so I think that’s something we have to dispense with. That is often something that happens in feminist spheres of viewing pop culture. We decide someone is an icon and then slowly begin chipping away as soon as they reveal that they are human and not perfect.

But that said, I do think that Amy Schumer is someone who is using a pretty potent mix of human and self-awareness and self-deprecation to talk about a lot of the double standards, in particular. I love the fact that, for instance, someone asked her, “Oh, isn’t it such a good time to be a female comic in Hollywood?” And she literally was like, “Are you fucking crazy?” She doesn’t buy into the hype of like, “Oh look, a few good things have happened. We’ve arrived. We’re in this golden feminist age.” I think that’s a really easy thing to fall into, feeling victorious and then stopping there, and I appreciate that she’s not doing that. And I appreciate that she has, in a lot of ways, pushed back on the idea that you have to be likeable if you’re gonna speak up about something and be really honest about it.

I think television in general has been an especially rich site of increasingly complex and challenging conversations around feminism and representation and anti-racism and a lot of these things. I think it just speaks to the idea that the more different lenses and backgrounds that people bring to creating and producing and directing, the more the medium is going to reflect people’s lives in the real world. And again, it’s not that there’s any sort of perfect feminist product out there, in terms of popular culture, but the fact that we’re seeing such a wide range of representations and points of view is really crucial.

So, Taylor Swift…

[Laughs] You know, I don’t really have a dog in the Taylor Swift fight, but I do think that her whole experience as a public figure grappling with feminism has been sort of a microcosm around our reaction to people declaring themselves feminists.

I wrote about this in the book. She was like, “I’m not a feminist; I don’t believe in girls versus boys,” and the internet freaked out. There was this whole cycle of response pieces: “Leave Taylor Swift alone”; “Taylor Swift is totally a feminist”; “Taylor Swift comes from a long tradition of country music women who were feminists, so even if she doesn’t think she’s a feminist, I’m saying she’s a feminist.”

And then she was like, “Oh wait, I’m friends with Lena Dunham now. Maybe I’m a feminist.” And then there’s a whole other cycle of think pieces.

I think it speaks to this idea of why we’re putting so much onus on individual celebrities to conform to an ideology and enact it in a way that makes us feel good as viewers. It, of course, turned into this whole “listicle feminism” thing, where it’s like “The Nine Most Feminist Things Taylor Swift Ever Said.”

It’s a very weird phenomenon, and I think her example really does typify how celebrity feminism becomes about the celebrity themselves rather than about feminism. It becomes about their bravery or their journey or their individual belief in what feminism is, rather than the fact that feminism is something that exists whether or not celebrities embrace it or not, and has very real consequences for people who aren’t celebrities and who aren’t able to put it on and take it off at whim.

Taking all this into consideration, obviously the struggle between pop culture and feminism, “the journey” anyway, isn’t going anywhere, and you really don’t want it to, either. What changes would you like to see to make things somehow less toxic than they can be, or generally better for feminism and pop culture together?

I do think that so much of it is about critical thinking and about really looking at the difference between politics and capitalism. We’re consumers. That’s what we’re encouraged to do; that’s what we are socialized to do; that’s what the media encourages in us. So even acknowledging that marketplace feminism makes sense in this very heavily mediated and capitalist world, I still think it’s worth trying to differentiate between what is trying to sell us stuff and what is trying to really talk about a more complex agenda toward equality and autonomy.

And then, looking more at systems than at individuals, and not necessarily thinking about feminism as something to consume. So, for instance, with movies, we’ve come to talk a lot about what’s OK to consume as a feminist movie. We talk about the Bechdel test, we talk about things like “Mad Max.” But I think maybe the more interesting, but more challenging question is: Is there such a thing as a feminist movie in an industry like Hollywood, which is still in many ways predicated on inequality? I think taking it out of the realm of the individual and the consumable and looking at feminism more as an ongoing, evolving lens, rather than a metric of quality, is probably a good way to go.