If you’re not from Louisville, Kentucky, you might not notice what was unusual about today’s memorial service for Muhammad Ali at the KFC Yum Center, as far as public events in this city go. There is no other way to say this — there aren’t a whole lot of spaces and times in this city where you see this many black and white residents gathered together to spend time in each other’s company, to laugh together, to pray together, to honor the same public figures, to reflect on what it means to be human and the responsibilities that entails.

I’m not saying never, of course. But the city has some bad habits, rooted in housing patterns that reflect midcentury white flight and housing discrimination and its long after-effects, along with good old-fashioned small-city tribalism — when someone asks where you went to school around here, they’re not asking about college — and just enough subtle racism (coded dress codes at a nightclub complex, for example) to keep the status quo intact. To actively disrupt those old bad habits takes a fight against inertia and apathy, even when, unlike big moments of outrage and grief that demand protest and action, the stakes seem deceptively small.

And yet here in the basketball arena overlooking the Ohio River today, an actual cross-section of the two communities came together, with distinguished guests and pilgrims, to honor the People’s Champ, Louisville’s native son. Chants of ALI! ALI! rang through the arena. A standing ovation for Lonnie Ali, the champ’s beloved widow, who was walked to her front-row seat by President Bill Clinton, who can bring down the house on any given night here as well.

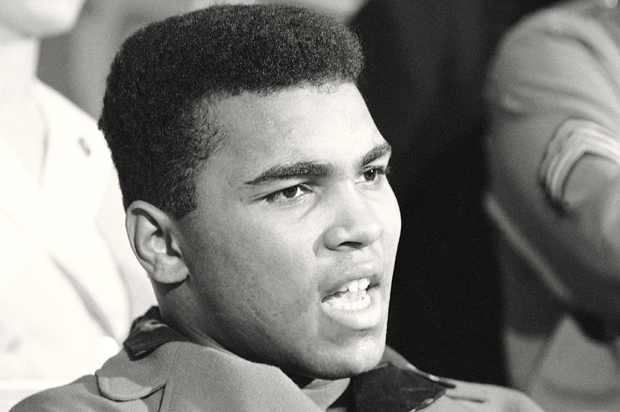

Earlier in the day, a motorcade of funeral limousines took Muhammad Ali’s body on one last tour of his hometown before he was laid to rest in the majestic Cave Hill Cemetery, where other famous Kentuckians like Colonel Harlan Sanders are buried, with movie star Will Smith and boxing champion Mike Tyson among the pallbearers. Thousands lined the streets to touch the cars, to chant and sing together, all along the route. City buses displayed cheerful “Ali the Greatest” digital signs, and the mood throughout the city going into the arena was jubilant: Men lecturing the children at their knees on why Muhammad Ali was the greatest man who ever lived. Women singing out, ALI! THE GREATEST!

Louisville can say this: We made Muhammad Ali. Louisville can say that with pride for his immense accomplishments and personal integrity and status as a symbol of justice and peace in the world. And Louisville, as part of an unjust country that has done its best to brutally de-personalize black men, women and children for centuries, can also say that with regret. We created the forces Ali had to fight against, without which he maybe would have been just a really great athlete, father, husband, philanthropist and friend.

I wasn’t born in the South, but I have spent most of my life in it. I will never get used to how clearly delineated its invisible fences can be. And yet there is also a long-running argument over whether Louisville is the southernmost Midwestern city, or the northernmost Southern town. Borderlands offer opportunity for reinvention, for absorption; they also brim with unspoken and contradictory rules. So in a city like ours, Muhammad Ali can grow up in the humiliation and brutality of segregation and yet be steered into his destiny by a white policeman who took an interest in a young man one day, proving, as Lonnie points out during her eulogy, that “any time a white cop and an inner city kid talk to each other, miracles can happen.”

The memorial honored not only Ali’s Muslim faith but also Buddhist, Catholic, Protestant, Mormon, Jewish and Native American religions, as well as the tenets of peace and justice. Speakers ranging from Ali’s daughters to close family friends like Billy Crystal, Bryant Gumbel, John Ramsey and Clinton himself, gave testimony to the man’s humor, intellect, appeal and impact. Not once in the three-hour interfaith service did anyone say Black Lives Matter from the stage, but it was explicit throughout the event.

And let me say this: If there are few times in the year when black Louisville and white Louisville get together just to hang out, there are even fewer times when 15,000 of us gather to go to church together like this — prayers in Arabic and English, Buddhist chants, calls for justice and an end to war, with Louisville’s own Rev. Kevin Cosby, pastor of St. Stephen’s Baptist Church, rhyming at the pulpit as he describes the sinister legacy of slavery and racism that Muhammad Ali fought against with his every public appearance and victory.

In the lineage of Jackie Robinson, Joe Louis, and Rosa Parks, came Ali, Cosby said, to knock out the destructive institutional belief that people of color were inferior, to demand that he be recognized as somebody.“All of our sacrosanct documents,” Cosby said, including the Constitution, “said to the Negro, you are nobody.” This, too, happened in Louisville.

Ali subverted that, and he did it with such flamboyance and with such integrity that America and the world had no choice but to take notice and to take his words to heart. And when he stood up to the U.S. government and let himself be stripped of all that he had fought for in service to an even bigger fight on behalf of oppressed people, his power only grew.

“From Louisville emerged a silver-tongued poet who took the ethos of ‘somebodies’ to untold heights,” said Cosby. “Before James Brown said ‘I’m black and I’m proud,’ Muhammad Ali said, ‘I’m black and I’m pretty.”

Cosby was followed by Ali’s friend and Republican senator Orrin Hatch, which was, if you ask the man sitting behind me, “a real slap in the face.” But when Hatch talked about going with Ali to see the Mormon Tabernacle Choir perform, and the funny scene of a crowd of autograph-seeking Mormons going home with pamphlets explaining Islam, Ali’s power to build bridges was clear. Some fights are waged through bold statements, others through subtle gestures.

Hatch was nearly forgotten, though, after Rabbi Michael Lerner, editor of the progressive Jewish interfaith magazine Tikkun, took the floor to demand accountability from the next American president — when he called her “she,” the room went crazy, by the way — for everything from drone warfare to income inequality to mass incarceration to racist drug laws to campaign finance, oh and also for Netanyahu to end the occupation of the West Bank while we’re at it. Lerner practically had to be pulled away from the podium for going over his time, and maybe for getting close to inciting a very well-intentioned riot, but nobody cared. ALI! ALI! ALI! The crowd roared in response. Those were, you could say, fighting words.

Even the more personal eulogies offered insights to Ali’s persistent fight for justice. Billy Crystal remembers Ali inviting his “little brother,” to jog with him on a closed country club golf course, and when Crystal pointed out that the club was “restricted” — no Jewish members — Ali refused to return, too. As Bryant Gumbel pointed out, “strictly speaking, fighting is what [Ali] did.”

When Bill Clinton finally brought the service to an end after nearly two dozen speakers, he called Ali “the universal soldier for our common humanity.”

Tomorrow, the motorcades will be a memory. Clinton will be somewhere on the campaign trail, maybe, trying to be of service to she who we hope will be the next president to heed Lerner’s call for justice. Ali’s family and close friends will continue grieving in private, and Louisville can easily slip back into its bad habits of disconnection and all the injustices that spring from it.

It is easy to remember Muhammad Ali as a great athlete, a wordsmith, a guy with a wicked sense of humor who knew how to undercut his buddy the ex-president’s pomposity by throwing bunny ears behind his head during the dedication of the Ali Center downtown. But Muhammad Ali was a fighter. He fought for justice and for peace, on both the large canvas and in many small moments.

It’s easy to say that Muhammad Ali belongs to all of Louisville, but what does that really mean? And what do we do with that connection? We could, perhaps, use it to fight for each other.

Today, Louisville calls itself a Compassionate City. What’s not to love about compassion? After all, as we learn early in life, it costs nothing to be nice. Compassion is a beautiful concept and according to the many testimonies given during the memorial, Ali embodied that virtue. He had a gift, according to the eulogies given by Crystal, Clinton and close friend John Ramsey, among others, for knowing when someone needed a mood lightened, a word of encouragement, a kind gesture. But a compassionate city and a just city — indeed, a compassionate world and a just world — are not the same things. Justice requires work. It demands sacrifice. Ali taught us that. And unlike compassion, it’s not always free.