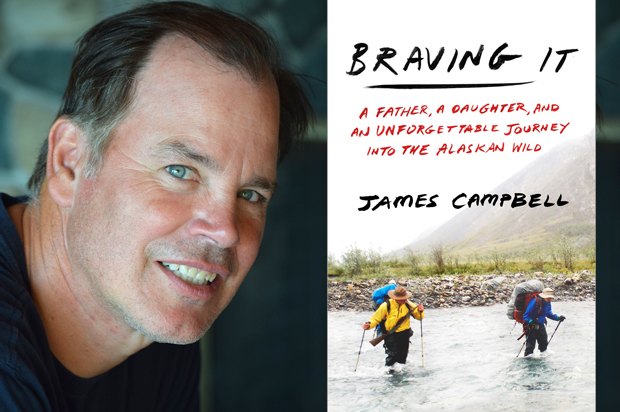

Adapted from “Braving It: A Father, a Daughter, and an Unforgettable Journey into the Alaskan Wild” Copyright © 2016 by James Campbell. Published by Crown Publishers, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

In 2013, James Campbell and his 15-year-old daughter Aidan made their first of three trips to Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which Campbell chronicles in his book “Braving It: A Father, a Daughter, and an Unforgettable Journey into the Alaskan Wild.” After a month-long cabin building project in the Refuge, they stopped in Talkeetna as a reward to Aidan. There Aidan demonstrates her newfound independence as she makes her first solo adventure, a thrilling plane ride to Denali.

One afternoon we arrived at the Talkeetna Air Taxi (TAT) airstrip for the last flight of the day and saw the mechanics readying the de Havilland Turbo Otter. As we’d hoped, the clouds had burned off, and, according to the woman at the front desk, the mountain was out. Visibility was as good as it had been in weeks. But she warned us that Denali and the other pinnacles of the Alaska Range—a rugged, four-hundred-mile-long chain of snowy peaks, where winds had been clocked in excess of 120 miles per hour—made their own weather. Fair skies could last for days or mere minutes.

The prospect of sending Aidan up alone with a bunch of people she’d never met before made me uneasy, but I had consulted the travel record for TAT online; it was excellent. I had emailed an old Alaskan friend, too, who said they were the best in the business, but then added, “Hope the weather is good. Flying the mountain is a life-changing experience—unless you run into the mountain, then it’s a life-ending experience.” In a follow-up email, he wrote, “Don’t worry about the local air taxis, they haven’t had an incident since Tuesday.”

I don’t mind dark humor, but when it involves my children I usually write the jokester off as an asshole. In this case, however, we had a long-standing friendship. What my buddy was referring to was the crash of a similar plane just the month before in Soldotna, on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula. The aircraft, operated by an air charter company, was flying two families, parents and children, to a fishing lodge when it struck the runway and burned shortly after takeoff. All ten people aboard had died.

Aidan had also heard about the crash, but if she was anxious about the flight she didn’t show it. Walking to the plane, she made a half turn and waved good-bye. There was an extra seat on the tour; I had to restrain myself from running into the office and buying it at the last minute. Later it would strike me as melodramatic, but as I watched her move away I wondered if I would see her again.

As the plane sped down the runway I realized that I, like many others, craved the illusion of control, the belief that I could exert influence over every aspect of Aidan’s life. I also realized that I was a hypocrite, plain and simple. Months before, I’d accused my wife, Elizabeth, of “catastrophizing,” of imagining the worst. Now, here I was, consigned to her role of waiting and worrying, allowing dark thoughts to fill my head. And yet, as the pilot lifted the Otter over the trees, I asked myself a simple question: what could I do if the pilot encountered a violent storm or high winds? The answer, of course, was not a damn thing.

Two hours later, I heard the Otter’s engines. The plane touched down and the pilot taxied over to where I was standing. Aidan was one of the last people to exit, and when she did, a smile lit up her face. She practically bounced over to me.

“It was amazing, Dad, beyond anything I ever imagined. I wish you could have been there, too.”

On the way into town she was manic, stumbling over her words, trying to find the language to convey what the experience meant to her, talking at a decibel level that might have made the scree tumble from the nearby mountains. She was joyful. She was not just counting her blessings, she was shouting them to the world.

She turned and spun around with her arms outstretched. “I know why he does it now.”

“Who?” I reply.

“Heimo,” she said, referring to my cousin, whose cabin we’d helped build in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. “He feels it.”

I looked at her, trying to follow, and she frowned. “The bliss,” she said. “Up there, flying close to the mountain, I felt like I was filled with nothing but joy. And I still feel it.” She ran away like a colt bolting across a meadow of spring grass.

“Hey, Dad,” she said, sticking her head in the belly of a plywood bear cutout. It read, catch ’em in talkeetna. “Take my picture. Who says I’m afraid of bears?”

It was a cheesy tourist’s photo, the kind that normally wouldn’t interest me. But Aidan was grinning from ear to ear, looking freer, fresher, and perhaps happier than I’d ever seen her.