I think of all the toughs through history

And thank heaven they lived, continuously.

— Thom Gunn, “Lines for a Book”

1.

In preparing remarks to introduce this anthology, I am, as usual, overcome by a stymying ambivalence. On one hand, I am tempted to use this space to take the literary world—publishing, the MFAs and AWPs—to task for so often misrepresenting, underrepresenting, sidelining, or even erasing, queer lives and queer voices. Lord knows I have anecdotal material. I would follow that by saying—ok, I am saying it now—that the writers contained herein represent the immense talent, the vast breadth, and the future, of queer literature today. Yet on the other hand, I’m exhausted a bit, by task-taking. And while I think it is necessary and right and good to critique the systems of power, and that enervation is hardly an excuse—I also long to write something enlivening, and to be enlivened in return. Underneath the ambivalence, I know only this—I love queer literature, it has sustained me. I don’t even know what my definition of queer literature is beyond, the books I love.

2.

This was on the radio. I was asked, Do you consider yourself a queer writer? I answered yes. Do you consider your book a queer book? Yes, again. But don’t you run the risk of your work being relegated to the gay section of the bookstore? Aren’t you—by calling yourself queer, by calling your book a queer book—complicit in your own ghettoization? I stumbled. I don’t remember how I answered. I ought to have been prepared. Being a queer writer means being asked, constantly, whether you consider yourself a queer writer—but I hadn’t yet learned that. Now I know. Folks listen to me speak, at literary festivals, on panels, at conferences, in bookstores, and while I am speaking, naming myself queer, they might interrupt. They might suggest I am limiting myself. More likely they will sidle up after, at the signing, or at a semi-mandatory dinner, and take it upon themselves to educate me about progress. A well-intentioned woman said to me once, not to worry, soon will come the day when it’s all just writing, just writers, no labels—and won’t that be nice? Aren’t you tired, she asked, of the gay ghetto?

3.

Am I tired of the ghetto? What even is the queer ghetto in literature, today? Is it cause for anxiety? Celebration? And if, as is claimed, it is disappearing, what might it be replaced with? To that end, it might be helpful to ask, what was the queer ghetto?

4.

Once upon a time, no babies were born in the queer ghetto. The queer ghetto was arrived at willfully, a radical choice, or through expulsion, an absence of choices. The families in the queer ghetto were chosen families, and notions of lineage, roots, were imagined—not in the sense of unreal, but unfixed. Queer lineage was brought into reality through the work of imagining backward; queer ancestry was fungible. Many of the writers anthologized in this book were born into ethnic ghettos, economic ghettos, the flavor and sounds of those places and those people concretely affected the consciousness of the forming self from the moment of birth. For all but very, very, few of us, the hands that touched us and raised us up, spanked and soothed us, were not queer hands, the voices that taunted and cajoled, were not queer voices. Families of origin, childhood itself, and the world of childhood, always exert a seemingly outsized influence on the adult—or as my boyfriend puts it much more succinctly, Childhood lasts a long time. If queers can be likened to wildflowers among the wheat, it is well to remember that on a subterranean level all our roots are tangled together. And well, too, to remember that the root is an active thing; the work of the root is more than anchor, the root pulls.

5.

Once upon time, the queer arrived to the ghetto, to queer culture, with a sense of disorientation—pushed out, despised by the straight world, but below the surface, those tangled roots, constantly pulling backward. One arrived stigmatized. One arrived at pride not as antidote to shame, or inoculation against shame, but as resulting vision forged in shame’s long fever. The hallmark protest chant, “We’re here, we’re queer, get used it to it!” was directed at a straight world that insisted on queer invisibility. Yet it has always seemed to me as equally applicable when looked at as a slogan the queer community speaks to itself. (Toto, Dorothy says, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.) Not being born in the queer ghetto, not being raised to be queer, it does take some getting used to.

6.

Life takes getting used to—that is, any life worth living takes getting used to. The seduction of mainstream culture is the promise that by remaining obedient to the models of life handed down, one will be freed from the difficulties of making meaning for oneself. One can stay in the garden and eat the unforbidden fruit; one will not be banished to queer ghetto. Rejecting authority, rejecting that which constricts, and making something of your life, that’s what queerness has always been about. Audre Lorde says, “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.”

7.

Of course to speak of a singular queer ghetto is itself an act of imagined history—the gay, lesbian, and trans communities, themselves further divisible along gendered, racial, kink, or political lines—were at times varyingly ignorant, supportive, dismissive, ashamed, and fed up with one another. But in the particular quality of stigma reserved for those who don’t conform to gender and/or sexuality expectations—they were united. They dared to act.

I think of those exclusive by their action

For whom mere thought could be no satisfaction—

This from Thom Gunn’s poem, “Lines for a Book,” the same poem used as epigraph to this essay. The poem is paean to macho activity, and a warning against the seductive, narcissistic, consolations of an inert self-consciousness (though the mind has also got a place / It’s not in marveling at its mirrored face), but can also be read as a poem about respectability, and about the way history treats those who act, who dare to fight, either by killing and forgetting them, or fundamentally altering them, desexualizing them, and making them respectable, before placing them on a pedestal.

The athletes lying under tons of dirt

Or standing gelded so they cannot hurt

The pale curators and the families

By calling up disturbing images.

8.

I claim as lineage, as ancestry, as queer, all those who dared to fight, who engaged with this stigma, who moved through it, or lived in it. When I read, “I think of those exclusive by their action / For whom mere thought could be no satisfaction—” I am thinking about those early queers who made the ghetto, all the queer writers who make queer literature, those who gave up any claim on straight world respectability, or straight world validation, and fought, wrote, screwed, acted.

9.

What is Queer Literature? What is Queer? The word itself is insult. I once went to a gay barbershop, and the gay barber damn near cut my ear off when I used ‘queer’ in conversation. We had a discussion, of sorts, about the reclamation and policing of language. He lectured and hated me and likened my using the word queer to spitting in his face. Needless to say I left with a fucked-up haircut. Queer is vague; queer hurts. Yet the word’s very vagueness means it depends less on a specific sexual orientation or gender-identity, than on a style that would make room for any ideas, any identity.

10.

Now, these days, things have changed in the ghetto. Now, respectability is within our grasp. Now gay marriage. Now babies. Now progress. Now pride. Leo Bersani writes, “I think that when (Foucault) told gays not to be proud of being gay, but rather to learn to become gay, he meant that we should work to invent realities that no longer imitate the dominant heterosexual model of a gender-based and fundamentally hierarchical relationality.” Even those who disparage Log Cabin Republicans and Andrew Sullivan’s yappings, often fall victim to the rhetoric of respectability politics. Triumphalism is the scourge of the gay rights movement.

11.

Have we won? How can we have won when there are still so many devalued positions we could make cause with? To my mind, queer literature resists, corrects, queers, triumphalist narratives. Queer literature is still becoming. Queer literature lends specificity to a conception that will always evade specific definition. Every queer story is an attempt to define queer life, and at the same time is an expansion of the definition of queer life. To my mind, queer literature is about the respect of difference, not the seductive respectability of sameness. To my mind, queerness has always been about identification and solidarity with the abjected and the devalued, the tossed off. Queerness has always been attracted to the forbidden. The first queer literary heroine I encountered was Eve, who dared to live a life beyond obedience. Eve, that witch, willing to take on all the shame, the stigma, the expulsion—not just to know, but to taste.

12.

Turn on the radio in these days of triumph. “Finally,” says a gay voice, “we’re just like everybody else. Finally my government recognizes my love as equal to anyone else’s.” I understand the sentiment, but the rhetoric is troubling. To focus on the state’s validation, or the validation of the church, or the validation of heterosexual society—is to give those institutions an awful lot of power of one’s sense of worth. According to Adam Phillips, “Freud says, don’t think about gods, think about parents: and then, when you forget about parents, see what you come up with.”

13.

Must we retreat? The official name for the assembly, the gathering, that united us all for one week, and which repeats itself yearly, is the Lambda Literary Emerging Writer’s Retreat. There is something both corporate and defeatist in the word retreat—but of course, there is also religion, spirituality. I’m not sure the title gives any sense to the emotional power and kinetic ferocity of gathering sixty talented queer writers together. This year, I overheard someone calling it The Annual Lambda Coven; I liked that.

14.

The morning the Supreme Court essentially legalized gay marriage I was in Los Angeles, teaching at The Annual Lambda Coven. Every author in this book was there along with me. The decision was expected, of course, the country and the court itself had been moving piecemeal, but decidedly, toward marriage equality. Of course, one never knows with the Supreme Court, so it was remotely possible they might “punt” as the pundits say, or shoot down same-sex marriage. Had they punted, I would not have been surprised, had they voted “no” I would have been furious. But that does not mean I felt victorious or uplifted by their saying yes. That morning I felt, as ever, ambivalent. I knew this was a landmark moment that deserved discussion, and as I walked to class I tried to imagine how that discussion might go—I didn’t want to insult the married, nor did I want to alienate the radicals. I needn’t have worried. I sat down with twelve queer fiction writers, some the most talented writers I’ve met, and I was reminded how diverse we are in our opinions, how ambivalent. I had twelve minds in front of me, each thinking for themselves what this moment meant, each teaching me.

15.

Respectability Anxiety. (Look, I’m a hypocrite. I’ll probably get married. My boyfriend is a foreigner, for one. But also, my desires are capacious—I want the marriage plot, I want the prince, I want adoptive fatherhood, and I want radical nonmonogomy and anonymous hedenonism. I want life. Legalize fucking life—and the hypocrisy it requires.)

16.

A dear queer writer friend accuses me of nostalgia. (Another accuses me of being a party-pooper). She asks, What’s the difference between feeling nostalgic for bygone eras and romanticizing suffering? Maybe she’s right. It is possible to look at the past with such a distorted sense of triumphalism—such schlocky, careless, ahistoricism and sentimentality—that you end up making the movie “Stonewall.”

17.

But maybe there is a difference, maybe there is a way, a backward glance, a queer nostalgia that is not restorative in its aim, but bent, reflective, critical. Heather Love says, “Insofar as (queer) identity is produced out of shame and stigma, it might seem like a good idea to leave it behind. It may in fact seem shaming to hold on to an identity that cannot be uncoupled from violence, suffering, and loss. I insist on the importance of clinging to ruined identities and to histories of injury. Resisting the call of gay normalization means refusing to write off the most vulnerable, the least presentable, and all the dead.” I like that.

18.

No well-intentioned person has ever suggested to me that real progress is a day when it’s all queer writing, queer writers—but that’s the only future I’m working toward. Sure that day isn’t coming, but nor is the imagined future in which queerness dissipates into the normal, when queerness is no longer necessary. The difference between our competing visions of progress is that the well-intentioned, straights, let’s call them, mistakenly believe their vision is an inevitability, while I know myself to be fighting for an impossibility. The only future worth dreaming is an impossibly queer future, a backward future. By that I mean a future that accounts for injustice, for hurt, for agitation—a future where injury is expected, and lived with. A future capable of looking at the past without scrubbing that hurt away, a future scarred by the past, and one that makes space for the scarred, for the backward-looking, the bent. To put it another way: Fuck progress. Fuck this relentless bettering. Fuck triumphalism. When it comes to making art, backwardness is as essential as vision.

19.

Do you remember the first time you read Zami? Trash? Or Stone Butch Blues? Or City of Night? Or Dancer From the Dance? Or Gender Outlaw? Or Girls, Visions, and Everything? Or Close to the Knives? I do—it was 1999. I was nineteen and had endured forced hospitalization, followed by a suicide attempt that left me in a coma, followed by further hospitalization. I took a queer literature class—I suppose you might call it Queer Ghetto Studies. For me it was an oasis. I remember the queer worlds, the ghettos, those books described. I remember feeling both nostalgic for bygone eras, some eras that I had barely missed, and wounded by all the hurt contained in those pages. I remember being nostalgic for even the hurt, even the wound—for the clarity, the call to action, that hurt provided, and the toughness required to survive. I think of all the toughs through history / and thank heaven they lived, continuously.

20.

This is book is an assemblage of toughs. To the queer reader I say, this is your family. These are your laughing aunties, your drunkles, your impossibly cool cousins. The imagined resemblances are real. You’ve got the book in your hands; welcome home.

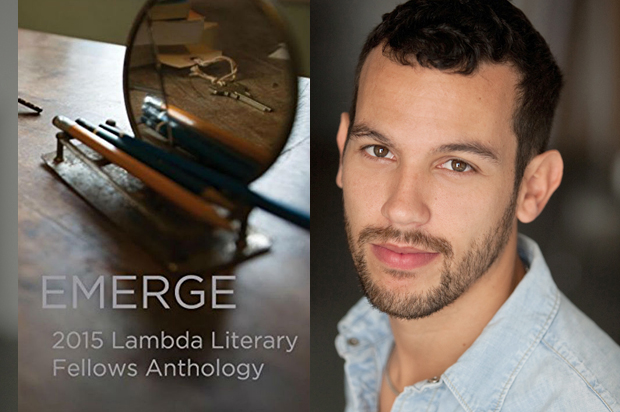

“Emerge: 2015 Lambda Literary Fellows Anthology (Volume 1)” is out June 23.