The series “Mad Men” was woven through with the music, literature, and other culture of the years in which it took place, even when it wasn’t made explicit. The New York poet Frank O’Hara, whose work came out a few years before and during the 1960-1970 period covered in the show, was both a visible and invisible presence in “Mad Men.”

In the first episode of the second season, a disoriented Don Draper picks up one of O’Hara’s books, “Meditations in an Emergency,” and a voiceover has him reading one of its poems, “Mayakovsky,” aloud. He then mails his copy to someone who we find out, episodes later, is Anna Draper, the California woman whose husband Don fought alongside in Korea. These small gestures tell us an enormous amount about Don Draper: His confusion about his own identity, his need to search for meaning, and his respect for Anna, who he sees as the only person who understands him.

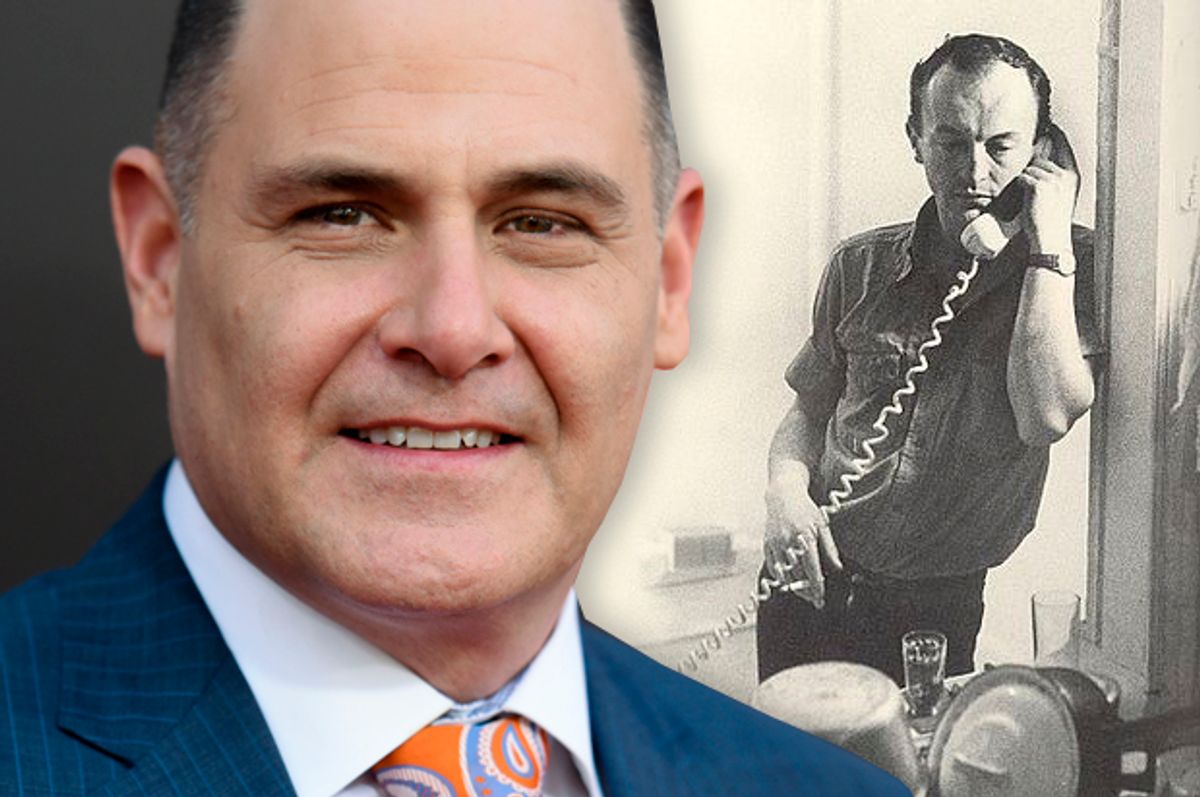

The show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, became a major O’Hara fan soon after discovering his work, and next week Audible Studios will release a recording of him reading O’Hara’s “Lunch Poems.” One of the classics of American poetry, “Lunch Poems” came out in 1964 and captures O’Hara’s distinctive combination of the daily mundane — walking through New York past taxicabs — as well as moments of the sublime and his engagement with the work of artistic titans like Jackson Pollock, Miles Davis and Billie Holiday. O’Hara was a curator at the Museum of Modern Art, and in some ways his writing resembles Abstract Expressionism and mid-century jazz. (Here is a recording of Weiner reading one of O'Hara's poems.)

We spoke to Weiner, who studied poetry as an undergraduate at Wesleyan, about O’Hara, his favorite writers, “Mad Men” and the complicated soul of Don Draper. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Let’s start with the fact that you describe Frank O’Hara, or at least his book “Lunch Poems,” as something that changed your life. How did you discover these poems and what appealed to you about them?

[“Mad Men”] was already underway. I had a pretty extensive education in poetry and everything that had excluded him, I guess because he was such an unusual… I don’t know why he wasn’t part of the canon, but he’s not. I don’t know why. It was not part of my education and like I said, I had a lot of poetry in my education, so that was weird.

But what happened is that my wife went to an exhibit for the Museum of the City of New York. It was photographs, mostly Garry Winogrand I think and some Weegee and just some stuff from the city, and in addition to that, next to each of the pictures was a poem on a sheet of paper, and they were all from “Lunch Poems.” So she brought me one of these poems back, I went and saw the exhibit, and I was just kind of blown away by the whole experience. It was just like total time travel, and he writes in a voice that you could say is conspiratorial, but it’s really more than that. It’s very present and it’s hard to believe that someone like that doesn’t exist anymore. It’s very alive. That’s the big compliment that I guess you give to something like that.

It’s a very romantic view of New York.

Yeah, some of it’s kind of sardonic and sarcastic and stuff, but yeah, it is romantic. It’s also very personal. But it’s very commonplace, it’s very workaday and familiar.

So when I got back to do the show for that season, which I believe is the beginning of Season Two, we had left Don in a kind of terrible place at the end of Season One where he was filled with regret, and Jon Hamm had talked to me about how this guy is probably going to get bored. So we had him go and get his physical and mix with people out in the street. I found out that “Lunch Poems” had not come out yet, so the rules of the show made it harder, but it still allowed me to get into Frank O’Hara, because “Meditations in an Emergency” had come out, which ended up being very fruitful and related to what I was doing and one of those coincidences that you can’t replicate. The show knows more than you do. It’s almost mysterious. I’m not kidding.

So that was my first interaction with him. And then I just really ate everything that I could find of his. I just read every single thing I could find. “Lunch Poems” was the book I bought and ripped my way through it, and then I found some recordings of him. Just his sense of humor, and he had such a large role at the Museum of Modern Art, so there’s an intellectual part of him also that’s not even in the poems.

My favorite sources for the show were people’s diaries, and I would always try and find any diaries that I could, either published diaries or sometimes people gave me friends’ and parents’ diaries, but anything that really had a kind of quotidian representation of life at that time. And the most important part of it is that when you’re dealing with historical context, when you read somebody’s diary you realize that, of course like any other thing in the world, that what’s going on for them personally has nothing to do with politics most of the time.

Frank really had that quality of, “This is what life is like. This is what’s on my mind. This is what I think is funny. This is what’s ironic.” And the whole process of writing “Lunch Poems,” which is what I liked about it, was that he was turning the necessity of doing his job into a poetic experience because he was compelled to write. That, to me, was related to Don at that time, and of course it became closely related to me.

Your job with these poems was to recite them, and you had heard recordings of O’Hara reading them.

I heard recordings of two of the poems that are in there. I tried not to imitate. But what you get is a man with a sense of humor who is performing in front of a crowd. There’s a series called “Poetry Speaks,” which has recordings of most of the poets of the 20th Century, at least most of the men, including Walt Whitman by the way. It’s a really amazing series.

I tried not to imitate him because he’s really mostly a stand-up, I think on some level, when he’s reading his poems. He had “Ave Maria” and “Greta Garbo has Collapsed.” The best thing is you can hear that he’s perfectly aware of the ironic, humorous voice that he’s giving and you can hear the laughter of the crowd.

I think the Billie Holiday poem, “The Day Lady Died,” is probably the other most famous Frank O’Hara poem.

From the “Lunch Poems,” yeah. I actually think that, Ironically, when we did find a piece of “Meditations in an Emergency,” my writer’s assistant at the time was like, “Are we gonna know what’s in the book or is he just sending this book” — we didn’t know it at the time — “to Anna Draper, and sort of saying even though I’m a suit and I’m an ad man, I am interested in poetry and I am interested in feelings and I don’t know what I am.” So I just flipped to the last page of “Meditations in an Emergency” and had him read it, and it’s from the poem “Mayakovsky,” which is probably one of the most-quoted things, which is the thing that Don reads in the show.

But as far as “Lunch Poems” goes, those are the most famous poems from “Lunch Poems,” and what I got when I was reading it, a book of poetry is sort of like being a D.J., I guess, like changing the pace up and putting different kinds of poems next to each other, and he knows a lot of French and a lot of it is about his travels and a lot of it is about his lovers, and so you get this kind of poetic diary when you read the whole thing at once. That was really one of the most moving things about the experience. There’s a conceit to this, which is that he’s writing these at lunch, supposedly some of them on typewriters that are in stores, just devoting himself to them.

There’s correspondence with him and Ferlinghetti, where he’s like, “I can’t find some of them,” and you get a feeling like, no, as a writer, he’s probably writing more of them. It’s kind of like, “I don’t have my homework.” But there’s an immediacy and a lack of formality, but the craft and his ability is kind of being hidden. It’s almost like a kind of modesty, that the construction is kind of being thrown away under the immediacy of the process that he’s describing.

Yeah, they’re so spontaneous.

Spontaneous, exactly. But they’re not. They’re not. When you read them you’re like, wow, this is not spontaneous. This thought is evolving over the next 30 lines, and this is not just a joke that’s being uttered.

I also like his I. And I don’t mean the eye as a visual eye, I mean the “I”. That’s very, you can’t use the word modern because it means so many other things, but it just cuts through time. You have someone standing next to you who feels so contemporary. I was always looking for it. It was one of the points of the show, just to say, “people haven’t changed.”

What other poets have moved you over the years?

I had a class called “20th Century Poetry,” taught by Gertrude Hughes, a Wallace Stevens scholar, but really what it was about, was women. So on the one hand, I’m coming out of high school with this personal relationship with Eliot and “The Waste Land.” Everyone gets into Eliot. I went to an all boys school. As soon as you read “J. Alfred Prufrock,” it’s basically like “Catcher in the Rye,” it just sticks with you. It’s a piece of art that resonates for a long time.

So I knew “The Waste Land” very well, and then everything else that we read, whether it was H.D (Hilda Doolittle), or Adrienne Rich, Elizabeth Bishop, Denise Levertov was really big, you start to get the political aspects of it. But also, I mean, Adrienne Rich’s book is called “The Dream of a Common Language,” and I would say emphatically that was what was going on in almost all of my poetry education.

I wanted to write poetry and I sought out Frank Reeve to be my personal tutor because I couldn’t get into a writing class, so I wrote with him for like three years.

He was a great teacher. And he made me read a lot of stuff that I would have never come in contact with. Obviously I have a real education in a lot of romantic poetry, I read Baudelaire, I read Wordsworth. But poets would come to read there. Mark Strand came to read, Derek Walcott came to read, Sharon Olds, I love Sharon Olds. You’d start to meet people who were alive right now, writing in a voice sometimes profane, whatever was the style. I love the density of poetry. I’m not a great reader of large things. I’m a slow reader, but I was always good, from high school on, we did “Paradise Lost” and a close reading of Milton, and I could take apart five or six paragraphs of that with complete understanding of ambiguity. I don’t know, poetry used to be a big part of the curriculum. I don’t see my kids doing it that much. We had to memorize everything. We had to memorize “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and the preamble of Chaucer. I was in “Under Milk Wood,” so I had memorized all this Dylan Thomas. You just get this linguistic fireworks. I love Sylvia Plath too, I have to say. Sylvia Plath is all over “Mad Men.”

I was about to ask, to what extent did O’Hara and other poets of the ‘60s have a shaping influence on “Mad Men” and its characters? Did you ever think about which characters might be into certain poets?

I did sort of think about the standard of education and that this was a more popular art form. Certainly you’ll see Jack Kerouac all over the first season. You’ll see Allen Ginsberg throughout the entire series. You’ll see Bob Dylan all over. You’re trying to say, what is the language of people’s lives? What are the thoughts that are coming through in the culture? You can’t talk about that decade without talking about “Catch-22,” for example. What were the poems that were the equivalent of that?

But in the end, what I really like about it is I feel like poetry is best unexplained. In this case it’s an audiobook so my voice might be interfering with Frank’s, but the writers that I love have moments of poetry whether they’re writing poetry by itself [or not]. That is, images, ideas, presented in their full ambiguity, where your brain understands it even if you can’t write a paper about it. Your brain understands the opposites being held together. So we always tried to do that with stories, so that emotional resonance wouldn’t be explained, and I always thought that that was inspired by my attempt at poetic storytelling.

As for characters, Peggy didn’t go to college, so she’s self-educated. Don is curious. Don will read anything. Don has an appetite for everything, so he’s not going to exclude anything.

He was interested in bohemia even though he wasn’t a bohemian himself. He was always searching for the edges of things, it seemed like.

Yeah. I mean, he’s the enemy of the bohemians. That’s the funny part, saying like, “Don’t just a book by its cover. You don’t actually know what’s going on in my mind.” Which I do think was part of the story of the show. The uniform that people are wearing, even if it has to do with their job, their money, their life, does not have anything to do with what their inner life is. But I love that everybody was educated. Roger can quote poems. It might be “The Charge of the Light Brigade” or something like that, but it’s education. Duck, I’m sure, had memorized some Kipling. Bert Cooper, he’s definitely an educated person. It’s where big ideas are held in few words, so that’s something that people carry around with them. Also, it’s a common language at that time. You’re expected to know what something’s in reference too.

Yeah, you can see Joan, as she went on after the show, getting into Anne Sexton or something like that.

Or Rod McKuen. [Laughs]

Yeah. Reassuring poetry.

Yeah, exactly. Joan probably has a weakness for the troubadours. I think it’s all about concentrated thought and the common reference of language that everyone is supposed to share. I don’t know what’s left now as our common references because we read so many different things and people have their phones so they’re not expected to actually know anything. But I suppose the Bible is still present, Shakespeare is still present, “Casablanca,” “The Wizard of Oz,” these are things that you’re expected to know. If someone 20 years old says something like, “Of all the gin joints” or “We’re not in Kansas anymore,” that’s the way a poem would function as shared cultural experience.

But you’re right, there are fewer and fewer of those. Part of the story of “Mad Men” is seeing that consensus fragment.

That is the best way to put it. Consensus fragmenting. I always felt like, you look at the bestsellers and they have such a high standard of attention required.

The bestsellers of that era you mean?

The bestsellers like “Catch-22” or “The Naked and the Dead.”… Popular entertainment is not always meaningless just because it's not considered art. This is gonna make me sound older than anything else I’ve said in this conversation, but I do think that there's a pride and expectation in being educated.

In that era, you mean?

Yeah. Bobby Kennedy is writing one of the great speeches that he gave, on the night that Martin Luther King was assassinated, where he’s going to Indianapolis, to help hopefully alleviate all of the social tension that’s pent up and all the rage that’s going on about the assassination, and he writes this down like the Gettysburg address on the back of a napkin and it starts off with a quote from Aeschylus, and no one said to him, “Hey the audience is gonna hear the word Aeschylus and walk away.” [Laughs.]

And maybe everybody doesn't know what that is, but you might go and find out what it is or know that it’s something very old, and that if this man has picked it as his reference point when he’s talking about, for the first time actually, talking publicly about the loss of his own brother to an assassin, it just becomes huge shades of emotional tone that are… I don’t know, the sort of anti-intellectual populism... I know that it’s dropped out of the culture for the time being. Which is funny because all of the predictions not reading were wrong. People are reading plenty. They’re just not proud of it. Or using it to communicate.

It sounds like you need to do a few more seasons of “Mad Men”; I’d like to see some of these ideas worked through in 1973 and 1974.

I’ll find something else to work it out in. The greatest thing is that I was surrounded by such smart people whether it was the actors, the writers, everybody was constantly bringing in pieces of art of all different forms. Whether it was a movie, or poem or comic, a song, the reflection that art can offer in troubling times, and that artists can offer who are often observing what’s going on rather than participating, sometimes, it was very stimulating and comforting, and so I’m always looking for a way to do that. I think that when people read “Lunch Poems,” they’ll be shocked that it’s so old, and they’ll be shocked that you can feel Frank — that you know somebody like Frank, probably. And you’ll be shocked at what he thinks is important to tell you, because it’s very intimate. And hopefully the recording brings that to it.

Shares