This article originally appeared on AlterNet.

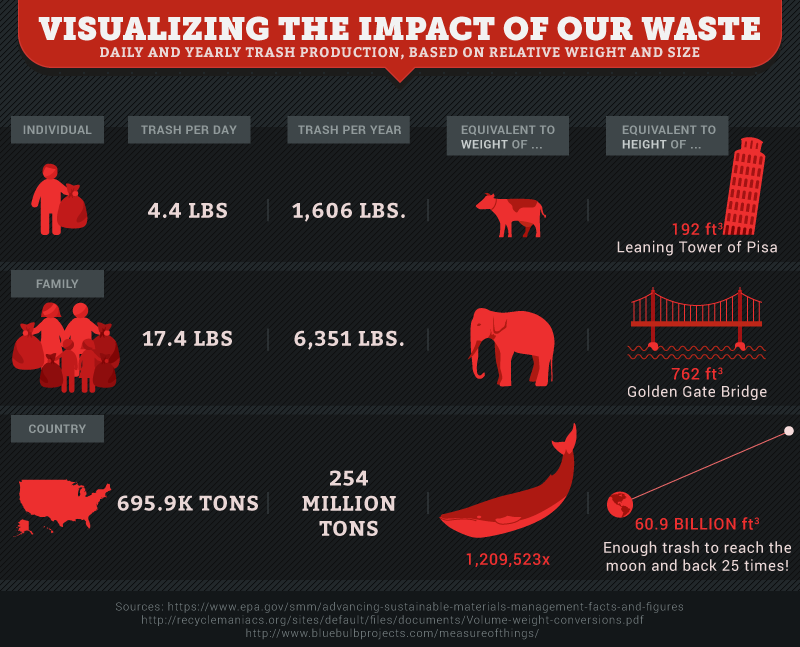

The EPA estimates that Americans generated about 254 million tons of garbage in 2013. That is a shocking amount of waste. Among developed nations, only New Zealand, Ireland, Norway and Switzerland produce more municipal solid waste per capita.

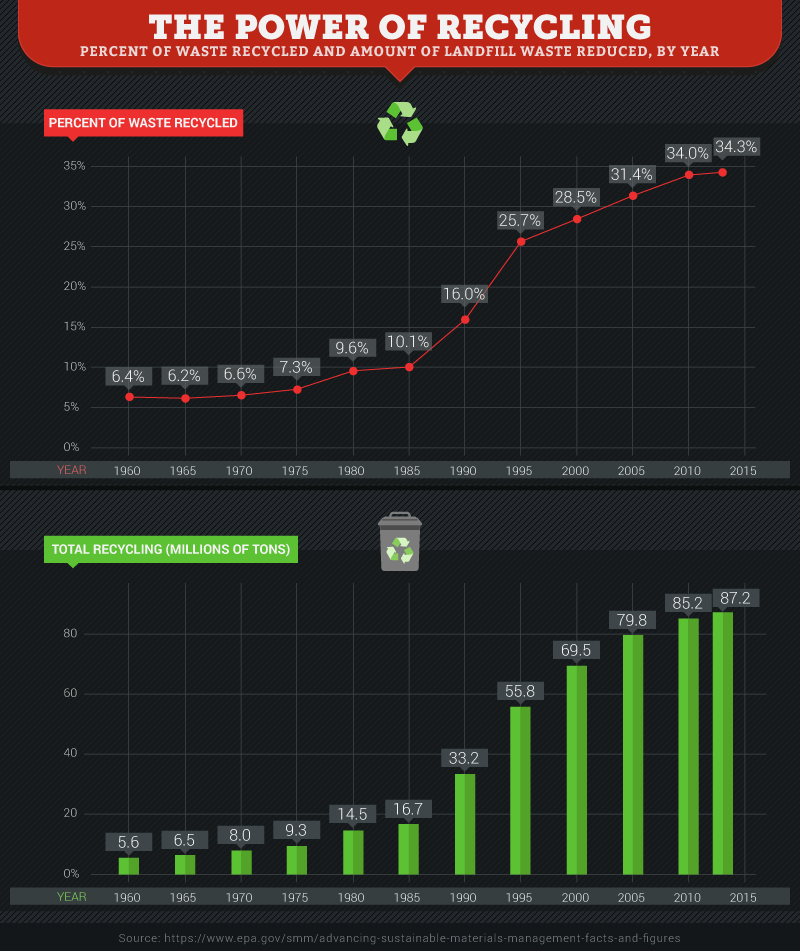

The good news is that the average American also recycles and composts 1.5 pounds of daily garbage. Last year, the U.S. recycling rate hit 34.3 percent, an all-time high. The bad news is that the rest either was incinerated or ended up in a landfill.

But though the U.S. recycling rate has been steadily rising — it was just 6.2 percent 50 years ago — America still lags behind several other developed (and nearly developed) nations, including Italy (36 percent), the United Kingdom (39 percent), South Korea (49 percent), Taiwan (60 percent), Austria (63 percent) and Germany (62 percent).

It’s hard to overestimate the importance of recycling and composting our garbage, and not letting it end up in a landfill. According to the EPA:

Recycling and composting prevented 87.2 million tons of material from being disposed in 2013, up from 15 million tons in 1980. Diverting these materials from landfills prevented the release of approximately 186 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent into the air in 2013 — equivalent to taking over 39 million cars off the road for a year.

However, while recycling has become an environmental mantra, it remains somewhat of a contentious issue. The New York Times writer John Tierney has been a fierce critic of the practice, writing in 1996 that recycling may be “the most wasteful activity in modern America: a waste of time and money, a waste of human and natural resources.” Nearly two decades later, he revisited the topic and came to a similar conclusion: “Despite decades of exhortations and mandates, it’s still typically more expensive for municipalities to recycle household waste than to send it to a landfill.”

Tierney’s critics are quick to point out that the issue is more complex than that. David Biello, an associate editor at Scientific American who has long covered environmental issues, argues that “the value of recycling depends on the material in question.”

Glass, for example, is costly to recycle and is made from a readily available material: sand. “What makes recyclables valuable is their rarity,” says Steve Shannon, an ecologist and municipal services manager at Balcones Resources, a recycling firm based in Austin, Texas. “Trees are scarcer than sand.”

Beyond the financial question is a more complex psychological dimension — those of us who recycle may have the false belief that overconsumption is acceptable. Kenneth Worthy, author of “Invisible Nature: Healing the Destructive Divide between People and the Environment,” explored the self-deception that may accompany recycling in Psychology Today:

When consumers see the recycling symbol, they may think that the product is without environmental costs … or that purchasing is actually an environmentally positive act. So the recycling symbol on the bottle or just the idea that we can recycle stuff when we’re done with it may actually lead us to buy more stuff than we need in the first place.

That’s the rebound effect — the idea that a product is more efficient or recyclable may make people buy more and thus cancel out the purported efficiency, perhaps resulting in more overall environmental damage.

But the ongoing debate over the relative merits of recycling misses a much more critical issue: We consume too much to begin with. And with a steadily growing population, that means steadily growing trash.

So it’s no surprise that over the past century, the United States has had to increase the number of landfills across the country. The graphic below shows the growth in both number and size of landfills over the past 100 years.

However, the EPA reports that the number of active municipal solid waste landfills in the country has decreased from approximately 7,900 in 1988 to 1,900 in 2009 — though the number may be slightly deceptive, as there has been some consolidation of multiple landfills, and landfills are able to accept more trash due to advancements in technology.

While the amount of garbage Americans produce is high, there are big differences when you look at the numbers for each state. The three states that produced the fewest tons of garbage per person are Idaho (4.1), North Dakota (5.2) and Connecticut (7.3). Those states stand in stark contrast to the three states that produced the most tons per capita: Colorado (35.2), Pennsylvania (35.4) and Nevada (38.4).

Again, the numbers may be a bit deceiving. The interstate trade in garbage is a $4 billion industry, so many state landfills will accept the trash of other states. In 2005, more than 42 million tons of municipal solid waste — about 17 percent of that year’s trash — crossed at least one state line before it was placed in a landfill.

While carbon dioxide emissions are a main concern about landfills, another is their production of methane, a greenhouse gas that is more powerful than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the Earth’s atmosphere.

According to the EPA, methane causes 21 times as much warming as an equivalent mass of carbon dioxide over a 100-year time period. In the first 20 years after its release, the intensity is much more severe. During that time period, methane is 84 times as potent a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide. California and Texas, with their high populations, have the greatest landfill-related methane emissions.

All that methane is produced by organic trash like food waste and yard trimmings. While it can be argued that some bushes need to be trimmed, it’s hard to make the case for throwing away food, which makes up more than a fifth of the nation’s waste stream — more than any other material that ends up in an incinerator or landfill.

Danielle Nierenberg, president of the nonprofit organization Food Tank, writes in a recent email:

At least 1.3 billion tons of food is lost or wasted every year — in fields, during transport, in storage, at restaurants, and in markets in industrialized and developed countries alike. In rich countries alone, some 222 million tons of food [are] wasted, which is almost as much as the entire net food production of sub-Saharan Africa. And according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), wasted food costs some $680 billion in industrialized countries and $310 billion in developing countries.

But things could be changing on the food waste front, with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the EPA setting the first-ever national food waste reduction goal, aimed at cutting national food waste in half by 2030.

There are many ways each of us can cut down on our personal waste. The Solid Waste Management Coordinating Board, which has worked since 1990 to improve the efficiency and environmentalism of the solid waste management of the Twin Cities metro region, offers the following ways to reduce waste.

- Bring reusable bags and containers when shopping, traveling or packing lunches or leftovers.

- Choose products that are returnable, reusable or refillable over single-use items.

- Avoid individually wrapped items, snack packs and single-serve containers. Buy large containers of items or from bulk bins whenever practical.

- Be aware of double-packaging — some “bulk packages” are just individually wrapped items packaged yet again and sold as a bulk item.

- Purchase items such as dish soap and laundry detergents in concentrate forms.

- Compost food scraps and yard waste. Food and yard waste accounts for about 11 percent of the garbage thrown away in the Twin Cities metro area. Many types of food scraps, along with leaves and yard trimmings, can be combined in your backyard compost bin.

- Reduce the amount of unwanted mail you receive. The average resident in America receives over 30 pounds of junk mail per year.

- Shop at second-hand stores. You can find great used and unused clothes at low cost to you and the environment. Buy quality clothing that won’t wear out and can be handed down to people you know or to a thrift store.

- Buy items made of recycled content and reuse them as much as you can. Use both sides of every page of a notebook and use printed-on printer paper for a scratch pad.

- Also, remember that buying in bulk rather than individual packages will save you lots of money and reduce waste. Packaging makes up 30 percent of the weight and 50 percent of trash by volume. Buy juice, snacks and other lunch items in bulk and use the reusable containers each day.

The full SaveOn Energy report can be found here.