In January of 2014, The New York Times published an essay on the cover of its Sunday Review section titled “For the Love of Money.”

“In my last year on Wall Street my bonus was $3.6 million – and I was angry because it wasn’t big enough,” the author, Sam Polk, began. Polk – a former hedge fund trader who left Wall Street and launched the education- and nutrition-focused nonprofit, Groceryships – went on to describe himself as a “giant fireball of greed” who once craved money the way an alcoholic craves a drink.

But the piece was more than just an admission of pathological greed; it was an indictment of a culture filled with – indeed, run by – addicts like Polk. “Wealth addicts are, more than anybody, specifically responsible for the ever widening rift that is tearing apart our once great country,” he wrote. “Only a wealth addict would feel justified in receiving $14 million in compensation – including an $8.5 million bonus – as the McDonald’s C.E.O., Don Thompson, did in 2012, while his company then published a brochure for its work force on how to survive on their low wages. Only a wealth addict would earn hundreds of millions as a hedge-fund manager, and then lobby to maintain a tax loophole that gave him a lower tax rate than his secretary.”

“Look at the magazine covers in any newsstand, plastered with the faces of celebrities and C.E.O.’s; the superrich are our cultural gods,” he continued. “I hope we all confront our part in enabling wealth addicts to exert so much influence over our country.”

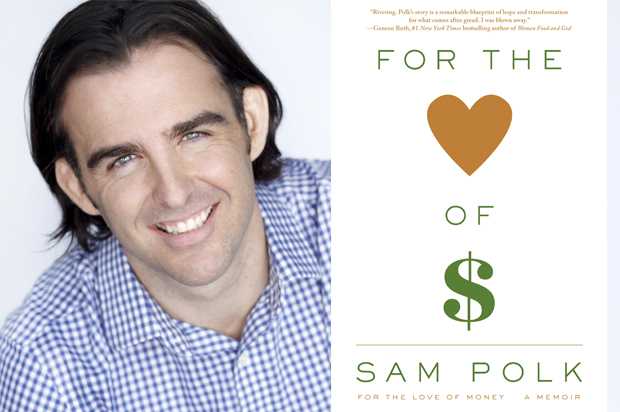

The article went viral, reaching more than 1.5 million readers. And in the months that followed, Polk appeared on Tavis Smiley’s show, wrote a follow-up commentary for CNBC, and faced an uncomfortable cross-examination by two hosts on a “Bloomberg” TV show. Now, two and half years later, he has written a memoir.

The core tension of that book, also titled “For the Love of Money,” is similar to the op-ed. Both are about what Polk described in the Times as, “recogniz[ing] my pursuit of wealth as an addiction,” and working to “heal the parts of myself that felt damaged and inadequate, so that I had enough of a core sense of self to walk away.”

But the scope of the book is much wider. There are scenes of childhood trauma and accounts of bouts with bulimia, alcoholism and drug use. There are fistfights, burglaries, sexual escapades and interludes at Columbia University and a Bay-Area tech startup. And, eventually, there is a detailed account of an accelerated career in finance, from Polk’s days as an entry-level financial analyst for Bank of America in Charlotte, North Carolina, to the day he walked out of one of the world’s biggest hedge funds, “and into the bright light of the New York afternoon, with no idea what I was going to do with the rest of my life.”

I recently caught up with the 36-year-old Polk via phone to discuss a book that’s part coming-of-age story, part recovery memoir and part exposé of a rotten, money-drenched Wall Street culture. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Why did you write this book?

I feel like my overriding experience in my twenties, with this desperation for money and success, was true for a lot of people. But I hadn’t read anything that had explored that. So I wanted to write a book that explored my – and our – obsession with money and success, from a super-vulnerable and honest place.

Are you still addicted to money?

No, I’m way more balanced when it comes to money. Before I got to Wall Street, I was obsessed with money and success and I think a lot of that came from my dad, who was, as I said in the op-ed, a Willy Loman-type guy who was an unsuccessful salesman with huge dreams that never seemed to materialize. So, since I was a kid, I always had this idea that money and success would allow me to reach this fantastical place where everything was OK, and I felt like I was enough and beloved and successful. And, of course, you take a kid like that and put him on Wall Street, where the overriding value system is “How much money do you have?” – that created in me this raging desire for money. And that’s what the book is about.

And so when I left [Wall Street], I basically disowned all of that. For the next three years, I did volunteer work, and I ended up starting a nonprofit. And – long story short – two years ago, I had a daughter and …that moment really put things into perspective for me a little bit. I understood that I needed to provide her a living and do my duties as a parent, so I needed to not fully disown that part of myself that was looking for money. But [I] also [needed to] really own this part of me that really wants to help people. I think this new business grew out of that idea of money being a part of a balanced life, as opposed to the primary goal.

Why do you think people responded so strongly to your op-ed?

I think there were a couple reasons. “The Wolf of Wall Street” was out at the time and Wall Street becomes this sort of metaphor for people about people [who] have it all and what unbridled greed and success looks like. One of the benefits of how I wrote that piece was, I think, for the first time, it sort of allowed people into a Wall Street trader’s life in a way that they connected with and understood.

And then secondarily, I do think that as a culture, our primary value is money and success. But it’s sort of like the “Jerry Maguire” memo, “The Things We Think and Do Not Say”: People don’t really talk about how deep their ambition goes, and what it feels like, and how jealous they are of other people who are more successful than them. I did, and people connected with that.

You talk a lot about jealousy both in the op-ed and in the book. Do you think that was something just you were feeling on Wall Street? Is it something people ever talked about?

It’s nothing that is ever talked about. [Laughs.]

And, no, I don’t think it was limited to me. You should see the sort of cold conversations that happen around bonus time, where people are like, “Oh yeah, I got paid really well,” and then you’ll see a smattering of, “Oh, congratulations. That’s really great to hear.” But, behind that, you can tell there’s this deep resentment.

The Wall Street culture you describe is so dominantly male and macho. Perhaps jealousy is a form of weakness that macho men don’t want to admit to. You think that might be part of it?

I think that’s 100 percent right. And, actually, I have a [new] New York Times op-ed about some of those issues – about how male-dominated a culture Wall Street is, and how there’s no place for vulnerability or feelings or, in point of fact, women.

A big chunk of the book relates to women. And, at one point you talk about how you weaned yourself off of watching pornography. For folks who haven’t read the book, why did you include that? Is there a connection between that and the things you talk about in your first op-ed?

For sure. Obviously the biggest theme of the book is money. But the biggest sub-theme is women. Basically those are the two top-of-mind categories for most men in the world. And I wanted to write about both of them, and how both of them can become ways that people use to compensate for an inner lack. And that was certainly true for me. Like I said in the book, with [my college girlfriend] Sloane Taylor, she was this woman who was beautiful and successful and wealthy and looked great on my arm, and that did things for me in the same way that getting a million-dollar bonus did. Which is that it made me feel important and valuable.

To go even further to your point specifically about pornography, we live in this culture that basically objectifies women as sexualized creatures and collections of body parts and then uses them to make ourselves feel good and important, à la trophy wives. And if you think about pornography, as a whole, clearly it can become an addiction. But, even deeper than that, pornography really is, in my mind, less about sex than it is about power, and much more about degrading women in a sexual way to make ourselves feel powerful and important.

Sometimes I think that I sound like a moralizer here, and I’m not. What I am saying is that – I don’t know what the numbers are – something like 80 percent of men regularly look at pornography, but nobody talks about it, even though things like YouPorn are up there with Netflix and Amazon, in terms of the traffic. [This] is having huge repercussions on the subconscious psyche of our culture. And we’re actually not talking about it that much.

When you describe the book in those terms, it’s very much a book about masculinity in America in 2016.

It totally is. I really wanted to write a book that a kid in college – a male kid in college – could read. We hold up these young men [to] an ideal of masculinity that includes no fear, and no backing down, and no expressing emotions. And I know that, for me, I had a tremendous amount of emotion and fear and insecurity. So I tried to be as candid as I could about it in that book, hoping that there were kids out there who were struggling with questions about what to do with their lives, and questions about how to treat women, who maybe could finally get an honest explanation of, at least, what one person did.

Getting back to Wall Street, at one point in the book you talk about how, when you were working in finance, people in the world began to appear to you like “pawns in a trillion-dollar chess game.” As you describe it, you basically started to see the world in terms of dollars and cents. How did working on Wall Street change the way you see the world?

I would say that, in general, the book is about my awakening to a new definition of success that includes making an intentional contribution in the world. People sort of assume that I hate Wall Street, but I don’t. There were so many things that I loved about Wall Street, like how competitive it was, and how smart the people were, and how fun it was to basically play this huge video game for a living. But at the end of the day, the driving value system behind all of it was accumulating money for yourself. My fundamental realization on Wall Street was that, if that was the primary goal in my life, then I would never feel – call it what you will – “fulfilled,” “balanced,” or really, I would never feel like I had spent my brief years in the world wisely.

Despite those aspects of the industry you say you liked, you do come down very hard on Wall Street in the book. At one point you write, “Our obsessive accumulation of money had led to the widest inequality in centuries. Our hoarding had left millions of people unemployed, starving, and marginalized … Our greed was the source of that poverty. We were the source of that marginalization.” That’s tough stuff. How much responsibility do you think goes to Wall Street for some of those big issues affecting society?

A lot. But I think it’s also broader than that. In some senses, Wall Street is almost like the most concentrated and most emblematic of the type of capitalism that is rife and rampant in the world. And what I mean by that is there are so many industries – whether it’s the food business or the medical business or the oil business – that are really about creating wealth at the expense of other people. So I just think Wall Street is the most concentrated form of that.

But I do think there is responsibility there. When people go to Wall Street, they think that how you judge the quality of a job is basically whether you like your day-to-day skills. Is it fun to break down business reports? Is it fun to trade bonds and trade derivatives? And, if it is, then it’s a great career.

For me, I went through a process that was about saying, “OK, that stuff is fun. But when I start to situate myself in the broader context, then I have to face the reality that my whole job is about [increasing] profit margins and cutting down wages so that the companies I own securities in can be the most profitable. And all of it is about me basically accumulating without really producing anything except a good percentage return, on an annual basis.” And I just came to understand that businesses, I believe, are about solving problems. But businesses have now become something that creates problems. And I would like to be a part of switching that back.

I watched that video of you being interviewed on Bloomberg, and they – unsurprisingly, for that outlet – lay into you pretty hard. Is emblematic of the broader reception you got in the finance industry after your op-ed? Do people see you as a threat to Wall Street’s mystique or credibility?

The first thing I would say is that there’s sort of no underestimating how insular and cloistered and defensive of a culture Wall Street is. And that’s simply by the fact that this is an industry that has earned outsized profits for decades and has been the subject of tremendous amounts of criticism, some deserved and some not. And so [it] has built up defense mechanisms. And so if anyone comes out there saying anything, they’re going to get up in arms and dismissive. And I think that’s largely what a lot of – I would say the broader context on Wall Street – did.

At the same time, I’m very close friends with a lot of people on Wall Street. I got tons of emails from people on Wall Street saying they really identified with what I was doing. I can tell you this, incontrovertibly – at least, in my own mind – there are not a lot of happy people on Wall Street. Most people I know on Wall Street are sad, or wish they were doing something else, or feel trapped by the money. So what I’m talking about, I think, has some resonance for them. And it doesn’t mean people have to … leave their finance careers. But it does mean taking responsibility and making space for the parts of themselves that aren’t acknowledged in Wall Street culture, currently.

In both the book and the op-ed, you describe a scene at the hedge fund when you said during a meeting, “Don’t you think regulations make sense for the system as a whole?” And your boss says, “I don’t have the brain capacity to think about the system as a whole. All I’m concerned with is how this affects our company.” Here’s your chance: What reforms would you prescribe for America or Wall Street to make it a healthier, better place?

I would say, especially for America, it goes back to what I was saying about businesses solving problems rather than creating them. But think about how many businesses externalize problems. Exxon externalizes global warming and Coca Cola externalizes obesity and McDonald’s, in addition to externalizing obesity, has this famous help line for their workers to call in to figure out what government subsidies they can augment their paycheck with, so they can survive, basically. And so the first and foremost thing that I think needs to happen is for – and this sounds a little lofty and grandiose – is for capitalism to be redefined so that each business becomes fully internalized and fully-self-sustaining.

And then there’s obviously a huge amount of work that needs to be done in leveling the playing field. One of the things I’ll talk about in this [latest] New York Times article is about how Wall Street sees itself as this incredibly meritocratic culture. But, in truth, it’s more like the Andover lacrosse team – competitive, but only [within] a certain subset of the population. There’s very few women there. There’s very little diversity on Wall Street. So that needs to be opened up.

But I think the bigger sort of thing, going back to your question about this hedge fund, is – and this sounds lofty and grandiose, as well – the two sort of overriding characteristics of this country, of this culture, are, on one hand, this individualism that’s about self-reliance and free markets and free enterprise. And then on the other side is this idea of democracy and “Every life matters” and “Each person has exactly the same vote.” You could sum that all up as being “We’re all in this together.”

And I think that’s what my old boss’s comment spoke to: which is that Wall Street has become a place of individualism without any sense of how it impacts the rest of the people in that culture. And so I’m hoping that, through this book, but also through this new business that I’m starting, to provide an example of a different kind of corporation, that can be about a fully internalized company solving a problem and making life better for everyone that intersects with it. Rather than a vampire squid sucking the life out of it.

Do you think this country, as a whole, is addicted to wealth?

That would be a good question if everybody had all these savings and all this extra wealth but then kept working themselves to the bone to get more. But that’s actually not how it is. We live in a country where 50 million people are on food stamps, and [a huge] percent of people claim to be living paycheck to paycheck, and where the entire middle class has been basically crushed, so now it basically seems like you’re either poor or super-rich.

And [then there is] what the sort of lower end of the One Percent feels like. Most people that are making $500,000 a year – they definitely feel like they’re not making enough, and some of that is because of the wealth addiction. But also some of it is it because private schools cost a lot, and the cost of living for living in a good school district has gone up. So all of that is to say, people’s obsession with wealth, in some sense, is merited. Because we do have a culture of haves and have-nots.

The words “Wall Street” carry all kinds of meaning in our culture. They mean one thing to Bernie Sanders and another thing to the hosts of that Bloomberg who interviewed you. What do those two words mean to you?

I think it’s a metaphor for what’s best and worst about our culture. We are a culture of “manifest destiny,” and creating the largest economy in the world and the most successful companies. And a lot of that is embodied by Wall Street.

At the same time, we also, as a culture, tend to skew a little to the selfish and the greedy. And [we] forget to take care of people that maybe haven’t had the same luck and benefits as everyone else. And so I do think Wall Street becomes this sort of [“Great Gatsby”-esque] green light that people are both deeply envious of and also very angry at.