With Hillary Clinton’s historic Democratic party nomination still fresh in our minds, it’s now more important than ever that we honor and remember those who came before, who fought and worked and organized to make America a better, fairer place for the so-called “fairer sex.” Sure, we’ve come a long way (baby), but Clinton’s clinch is only one glittering milestone in a long and shining legacy of hard-won battles. Before women could dream of sending one of their own to the Oval Office (or of voting at all), they dreamed of controlling their bodies, and reclaiming their own flesh from an endless cycle of pregnancy, birth and, all too often, death.

That war continues to rage, but without the contributions of pioneers like Margaret Sanger, we’d still be stuck in the trenches. Born in 1879 to Irish parents, she was a complicated woman, one who’s best remembered as the tireless birth control advocate who scandalized the country, energized a generation of women and founded the nation’s first birth control clinic, planting the seed for the organization that would eventually become Planned Parenthood. She was also a radical activist, a mother, a wife, a nurse and an extremely savvy media wrangler who excelled at stirring up publicity for her cause (and landed herself in jail a few times as a result). Sanger’s refusal to back down or be silenced is echoed in the steadfast approach of Planned Parenthood itself, even as the problem she labored to correct — American women’s government-sanctioned lack of bodily autonomy — remains ingrained in our supposedly modern society.

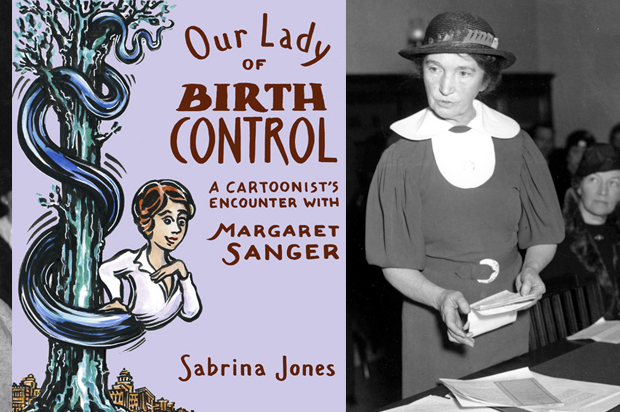

In her new graphic novel, “Our Lady of Birth Control” (Soft Skull Press), artist Sabrina Jones pulls back the curtain and beckons readers into the heart of Sanger’s story in an effort to humanize the woman behind the movement. Her bold, stark drawing style accentuates Sanger’s own boldness and brazen, joyous lack of delicacy. Sanger was a force of nature, a driven and determined fighter who changed the world, but, as Jones shows, it was far from easy going. The author deftly interweaves painstakingly researched, lovingly detailed segments of Sanger’s biography with her own narrative as feminist activist who came of age during the sexual revolution of the ’70s and has grappled with her role in the struggle.

Sanger’s own legacy is complicated, too, fraught with accusations of racism and a perceived championing of eugenics. Understanding 19th century viewpoints through a 21st century prism requires a generous amount of perspective, of course, and this story is no exception. That an outspoken, sexually liberated woman on a mission would rack up reams of bad press during (and after) her lifetime is less of a surprise than a given, but Jones does an admirable job of laying out and patiently dismantling the accusations leveled against Sanger and of explaining the contemporary social circumstances that birthed them.

It’s a deeply personal book for both parties, but the desperately human circumstances it describes — love, work, identity, autonomy, perseverance, death — are all too universal. I’d rank “Our Lady of Birth Control” up there with Kate Evans’ Red Rosa as one of 2016’s most crucial politically-charged graphic novels, and I recommend it to anyone with even a passing interest in the women’s rights movement — especially if you’re #WithHer, or more fittingly, #AgainstHim.

I got in touch with Sabrina Jones to find out more about the work that went into “Our Lady of Birth Control,” President Teddy Roosevelt’s surprising reaction to Sanger’s crusade, the current state of birth control access in this country — and how far we still have to go.

In the book, you share a few anecdotes from your personal activities in the women’s rights movement; without giving too much away, can you explain how you became involved in the struggle, and how that led you to Margaret Sanger?

As a teenager in the 1970s, I fully expected to enjoy the fruits of women’s liberation and the sexual revolution that had thrown off the shackles of the repressive post-war era. Even my mother shuddered at the mention of the dreaded 1950s. Imagine my shock when Ronald Reagan was elected on a wave of nostalgia for the bad old days! Born-again Christians mobilized, advancing legislation to repeal Roe v. Wade. My initiation into activism was with a group of pro-choice artists under the banner of Carnival Knowledge. We made interactive games and performances about reproductive rights, which we presented at street fairs, demonstrations, community centers and galleries. It was thrilling for me, barely out of art school, to throw my energies into the fray of the culture wars. But the carnival was cumbersome and labor-intensive, and it faltered as my heroic new mentors began to burn out.

Meanwhile, the editors of this anti-nuclear comic book called World War 3 Illustrated asked me do a comic strip about the battles over abortion. They were branching out to cover broader issues, and had seen Carnival Knowledge. I had never drawn comics, and rarely read any since outgrowing Archie and Veronica, but I thought WW3 shared many of the virtues of the carnival without its disadvantages. The comic book, like a carnival, is a user-friendly popular medium that can be a non-intimidating vehicle for a social message, but it is cheap and much more portable. Besides, I was not a natural performer, so I was much happier at the drawing table.

Years later, working on comics about the radical movements of the early 20th century, I fell under the spell of Margaret Sanger. Of all the radical ferment in Greenwich Village in the teens, Sanger’s fight to legalize birth control may have had the greatest impact on how we live now. She was a working class heroine, a racy bohemian and a tough-as-nails charmer who got results. With her story, I came full circle to the issues of women’s health and sexual liberation that had first motivated me to make political art.

How did you first become interested in creating historical graphic novels? It’s a really interesting niche and perhaps not the first thing that comes to mind when one hears the phrase “graphic novel.”

True. The most famous “graphic novels” are actually memoirs: “Maus,” “Persepolis,” “Fun Home” … and some of my personal favorites: “The Amazing True Story of A Teenage Single Mom,” “Pyongyang,” “The Photographer.” Oh, the pressure to have such an interesting life! Or to have the guts to be as honest as Harvey Pekar, Julie Doucet, Aline Kominsky Crumb. When I was asked to contribute to “Wobblies! A Graphic History of the Industrial Workers of the World,” I discovered a wealth of stories and characters, free for the taking, without having to go out and get into trouble or bare the tawdriest corners of my soul. From the comfort of my studio, I could resurrect the historical rebels they didn’t teach us about in school. The down side of immersing myself in the bold exploits of my predecessors is that makes my own life look like the intersection of boring and cowardly.

What was the research process like for this project? How long did it take you to finish the book? It must’ve been quite an undertaking, given the amount of detail you go into and the complexity of the subject matter.

Once Margaret Sanger became the face of the birth control movement, she used her renown to advance the cause, publishing a ghost-written autobiography that lacks all the juicy bits and difficult traits that make her so fascinating to me. A couple of good biographies and a three-volume edition of her papers — letters, diaries, as well as speeches and articles — fleshed out the picture. Due to the skanky image of contraception at the time, Sanger made a strategic decision not to mention her enthusiastic embrace of free love, her multiple affairs and her long-sought divorce. The public Mrs. Sanger was impeccably ladylike, even soft-spoken, and emphasized the desperate need for birth control on behalf of the impoverished wives and mothers she cared for as a nurse. Devoted to giving women control over their own fertility, she was a neglectful mother and a faithless wife. I was intrigued that such a great do-gooder was also quite a bad girl in private.

I collected addresses where Sanger lived or worked in New York, and gazed up at the buildings that still exist on 5th Avenue and 16th Street. The now-replaced storefront where she opened her first outlaw clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn, 100 years ago this October 16th, is especially resonant. The neighborhood is still low-income, although African Americans have replaced the East European and Italian immigrants Margaret served. She succeeded in legalizing birth control, but it failed to eradicate poverty as she hoped.

My work took about three years from conception to publication. Since the first three publishers I approached thought it was such a bad idea, I had the leisure of working without a deadline.

You did an excellent job of showing how interconnected the fight for women’s rights was with radical leftist political movements and the larger labor movement during Sanger’s time — a connection that all too often feels reduced to an afterthought in the current wave of pop feminism. How can we as feminists work to reforge that strong connection with our comrades in labor?

We have to be our own comrades, and acknowledge that we are mostly workers, too. As a union member (United Scenic Artists Local 829 — we paint scenery in the entertainment industry), I learned firsthand that unions are among the few places where men and women are paid equally for the same work. Problems arise when entire growing fields are feminized, like home health care, and consequently undervalued.

If, by pop feminism, you mean the idea that sexiness is powerful, then I’m afraid diamonds are still a girl’s best friend. The current reverence for entrepreneurs, the idea that we must all become cutthroat self-starters, is unrealistic about human nature. Where’s the respect for the average person who conscientiously does her job? Other than her entirely self-motivated career as an activist and organization builder, Margaret Sanger made her living in two conventionally female occupations: nursing and marriage. Her second marriage was far more profitable than her first. Even visionaries have to be pragmatic to get ahead.

Teddy Roosevelt’s quote, where he equated birth control to “race suicide” amongst “selfish,””cowardly” women of the “better classes” stood out — Roosevelt has such a cuddly image that most Americans don’t even know about his white supremacist views. Where did you come across that tidbit?

Margaret dropped pointed references to him in her speeches. Our former president, namesake of the Teddy bear, believed that if women had the choice, we would not have enough babies for the survival of the race. This concern for “race suicide” was often couched in general terms that could refer to the human race, but elsewhere it was clear that he was worried that “native born” Americans, who were in his time predominantly Protestants of Northern European heritage, would be outnumbered by more prolific immigrants, who were more often Catholic or Jewish, from Southern and Eastern Europe. Sound familiar?

Here’s [Roosevelt]: “If Americans of the old stock lead lives of celibate selfishness (whether profligate or merely frivolous or objectless matters little), or if the married are afflicted by that base fear of living which… forbids them to have more than one or two children, disaster awaits the nation. It is not well for a nation to import its art and its literature; but it is fatal for a nation to import its babies,” from Metropolitan Magazine, October 1917.

He further derided “birth control propagandists” as “decadent” and “immoral.” After handily rebutting him in the December issue, Margaret delighted in telling audiences that she received plenty of mail requesting birth control information from Roosevelt’s neck of the woods in Oyster Bay, Long Island.

Sanger was a polarizing figure, as we especially see in the section about the enduring controversy around her relationship with race and eugenics. It’s never easy to reconcile a revered individual with their mistakes or unenlightened views; how did you approach this section, and what was the main message you sought to convey?

Google “Margaret Sanger and race,” and brace yourself for a horror show of racism, genocide, the KKK and Hitler. Almost none of it is true, and that fraction which is factual is deceptively out of context. At Sanger’s first trial for offering banned contraceptive information to Jewish and Italian immigrants in Brooklyn, she was accused of aiming to eliminate the Jewish race. By the same twisted logic, her efforts to provide access to birth control to women of color in Harlem, North Carolina, and Tennessee are now cited as evidence that she wished to eliminate African Americans.

Sanger fought so that all women, especially those with low incomes, would have the knowledge and ability to make their own decisions about bearing children. Her outreach to the African American community had the support of leaders like W. E. B. Dubois, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and Mary McLeod Bethune. It was years later that opponents of abortion spread false accusations of racism, in order to alienate people of color from the pro-choice movement and Planned Parenthood. In fact, Sanger actively discouraged abortion, which she hoped to avoid through birth control, and Planned Parenthood never performed abortion during her lifetime.

Sanger’s association with eugenics is trickier to understand, because we must realize that eugenics in the 1920s appealed to people across the political spectrum, was taught in 75 percent of U. S. colleges, and was considered far more respectable and scientific than contraception. Sanger sought the endorsement of doctors, scientists and academics to validate the birth control movement, which many associated with free love and anarchism. She wanted the eugenics movement to support birth control because she claimed it would lead to fewer, healthier babies, and reduce poverty, child labor and prostitution. She never supported coercive, race-based methods.

But her overtures were largely rebuffed by the pro-natalist eugenicists who feared, like Theodore Roosevelt, that birth control would end up in the wrong hands. After the horrors of Nazism, it’s hard to convince people that there was once a kinder, gentler interpretation of eugenics, but then Margaret had an equally hard time convincing eugenicists that her decadent, immoral methods would help improve the human race. And if you don’t believe me, Planned Parenthood has an excellent document online called “Opposition Claims Against Margaret Sanger.”

The amount of government opposition to birth control and Sanger’s work was intense during her lifetime, and it’s sad to see how little has changed in a century. Why do you think birth control’s modern opponents are still so afraid of women’s sexuality?

Now we have employers invoking “religious freedom” to deny birth control coverage in employee health plans. Before we even get into the specter of unfettered female sexuality, this issue betrays a profound disrespect for labor. Healthcare is not a gift from our employer. It is a benefit we earn with our work. Hobby Lobby, Little Sisters of the Poor, I agree that it’s none of their business whether their employees use contraception. Skyrocketing healthcare costs and the stranglehold of the insurance companies have empowered these employers to interfere in our private lives. If we had a real national health plan, the fight would probably continue in the halls of Congress. The desire to control women’s bodies is a primal expression of male power, rooted in questions of paternity. A cute baby peers from a billboard in my Brooklyn neighborhood, over the caption, “Does he really have his father’s eyes?” DNA testing. I imagine fathers dropping in on visiting day to make sure they haven’t been suckered into caring for someone else’s kid. But practical considerations aside, sex is powerful, and we play with fire at our own risk. All the more reason to take precautions.

What (or whom) would you consider to be the modern equivalent to Comstock and his repressive “obscenity” law?

[Indiana Gov.] Mike Pence, who I confess I hadn’t heard of before he was picked as Republican vice-presidential candidate, turns out to be a driving force behind the movement to defund Planned Parenthood, sponsoring legislation in congress as far back as 2007. Laws he passed in his home state have shut down clinics across Indiana. He tried to redefine rape as “forcible rape” to limit abortion funding. Restrictive regulations closed down many abortion clinics in Texas before the Supreme Court struck down the law. Since the anti-choice movement failed to repeal Roe v. Wade, they’ve concentrated on chipping away at access to it. The Supreme Court decision may have been ahead of its time, so we are still struggling to defend it. It’s not enough to change the law. We have to engage the culture to accept women’s right to control our own bodies and lives.

After spending so much time with her story, and now seeing the way that Planned Parenthood is still — still! — under attack, what do you think it’ll take for birth control to finally be accepted and legally protected as a right, a necessity and a choice that should be available to every person?

Even though birth control is infinitely better and more widely available than it was when Sanger started out, we still have many unintended pregnancies. Most of the fire against Planned Parenthood is aimed at abortion, not birth control, but we cannot separate the two. We are not perfect, and neither are all the methods. The attacks, whether they use laws or guns, not only limit access to services, they create a sense of danger and stigma around reproductive care.

When a woman is embarrassed to mention contraception to her partner, we are in danger. When she feels guilty about making plans to protect her body, we have failed. When she is blamed for being the victimized by rape or other sexual aggression, we need to stand up for her.

Shame and denial contribute to women’s lapses in self-care, but we also make mistakes. The ferocious political climate and self-righteous posturing about pregnancy make it hard to admit that we do make mistakes, in using birth control and in choosing our partners. When I was an adolescent, the sexual revolution beckoned us to a pleasure garden that turned out to have its share of thorns, and now young girls are under immense pressure to be “hot” before they can handle it. For this we should be punished? Young people need compassion and support as they navigate a new social landscape.

What do you think are the most effective ways that modern birth control advocates can continue the fight Sanger started?

As an artist, my weapons are the pen and the brush. I hope my stories and images affirm our right to experience sex, love and relationships in whatever form is right for us. Margaret may have buttoned up her libido in public, but her passionate spirit drove her to fight for all of our rights.

I’d like to see our country follow the example of Colorado, where a recent experiment with free, long-acting birth control has had fantastic results. Teen birth and abortion rates have dropped dramatically, and millions of Medicaid dollars were saved.

I am also very impressed by the networks of abortion funds and volunteers who host women who need to travel for healthcare because their local clinics are shut. But better that the clinics remain open and fully funded for all women! Support Planned Parenthood and elect more women and other pro-choice candidates.

Your quote about “the perfect confluence of art, activism and love” really struck me; it’s a beautifully simple but effective way to sum up some of the guiding principles of Sanger’s life’s work, and to wrap up your own journey. Do you view creating this book as a political act, or more of an act of personal fulfillment (or, as I suspect, both)?

Now that I see those words out of their original context, I wish it were used to describe my book! Ironically, that moment of “perfect confluence” soon hit the rocks, and I was once again scrambling for balance. I held back from activism for fear that it would keep me from the studio. Getting up at dawn to defend clinics can take a bite out of your creative energy. Demonstrations weren’t as exciting as I remembered, maybe because the police got so good at fencing us in. Instead of claiming the streets, we’re taken for a walk between barricades. It was the opposite of empowering. By the time Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter came along, proving the impact of a robust protest movement, I had come to terms with my place at the drawing table. I no longer feel conflicted about skipping a protest to stay home and draw, because making comics about social justice is the best way for me to contribute.

By now you’ve profiled larger-than-life figures like Isadora Duncan, Margaret Sanger, the Wobblies and numerous others—who’s next on the docket for you?

I’m working on a short strip for World War 3 Illustrated, the radical comics magazine that has fostered my comics since the beginning. It’s called “Hear that Whistle Blow.” It’s about the trains full of crude oil that roll through our communities, putting them in the path of potential disaster. The ideas that are calling to me for the next project are still too farfetched and tender to reveal in print. I’ll just say that my next book may be a lot more personal, and combine history, memoir and travelogue.