If you’ve ever wondered where forbidden words come from and what they do to us, “What the F” is the book for you. Subtitled “What Swearing Reveals About Our Language, Our Brain, and Ourselves,” the book tells a crisply accessible tale that also includes comparisons to other cultures, where profanity works differently. (In Japanese, for example, swear words don’t really exist.)

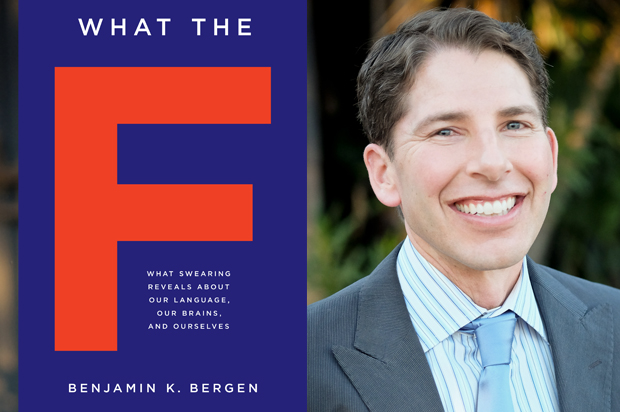

Cognitive scientist Benjamin Bergen, who teaches at the University of California at San Diego, spoke to Salon from his campus office. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Let’s start with the word most of us learned early on was the biggest, scariest, nastiest, dirty word of them all, the one your title turns on: the F-word. I’ve heard all kinds of theories as to where it came from. What are its origins, and has it always been such a forbidden, dangerous term? Was it ever an acceptable word?

So the word, as far as we can tell, is very, very old. It’s thousands of years old and comes from a root that means something like to strike or rub. For most of its history, it has not had any profane meaning at all. The first time we know it starts to have the meaning “to copulate,” as it now does, is as early as the 14th century, A.D. It comes from some legal proceedings, in which there was a defendant who had that as part of his last name. His name was Roger Fuckebythenavel. It appears to have been his real name.

But through Shakespeare’s time, it didn’t seem to have been as profane as it became in the 20th century. That only started to be the case around three centuries ago. In Shakespeare’s day the equivalent term was “swive,” which was far stronger.

And like a lot of words in English, this came from Germanic roots or Anglo-Saxon or something?

That’s right. This comes from the Germanic line. And there are therefore similar words you see in Norwegian and German, where there’s a similar word — “ficken” — that has a similar meaning but is far less profane than the English word.

The interesting thing about the F-word is that according to survey data, it’s progressively becoming less offensive. And if you talk to young people today, it’s not even the most offensive word in the language; that title belongs to the N-word.

Right, your book documents the most forbidden word in English-speaking countries, and in some cases the F-word is fairly far down the list.

So what do all these words that are in English the nastiest, most forbidden, most taboo have in common? Do they have something that makes us want to wall them off from public places, respectable homes and so on?

You’d think so because they tend to be words that describe sex, sex organs, other body parts, things that come out of those body parts, outside groups, forbidden terms and concepts. But that’s not enough to make a word profane. There are words you’d use with your child or your doctor to describe, say, feces or sexual intercourse. The strongest predictor of what words you’d consider profane are words that you as a child would have been punished for using. It’s a social construct.

Are these words harmful, dangerous? Why are we as a society — and we’re not unique in this — walling off these words? Is there something rational behind it?

For some words, maybe. For words that denigrate groups of people — social-group affiliation, race, sexual identity and so on — there’s actually some experimental evidence that shows that being exposed to those words causes harm and discrimination.

But for the most part, your run-of-the mill taboo words — your F-words and sh-words — there’s no evidence they cause any harm. That’s true of children’s exposure or adult use of the words. Much of the fear is that they will stunt children’s vocabulary or lead to aggression. But that’s not borne out.

In some places these words are strictly illegal; in other cases the restrictions are softer. In a just and rational world, would we limit these words? Would that be a healthier society, if we could use these words whenever we wanted?

Another way to ask the question is: Does France have a better grip on language policy than we do? In France the two worst words in the language — “foutre” and “putain” — are regularly used around and by children, in an office environment, in national addresses. Even though they are the equivalent of our F-word.

And I think we picture the French shouting “merde!” all the time, right?

That’s right. And if you think of “merde” as the equivalent of our sh-word, it’s used far more frequently there.

So it’s certainly possible to have a society that uses that social model, but to ask what’s the right social model assumes a little bit of objective privilege.

Is there any downside to having a freer flow of language? Of dropping the prohibition against these problematic words?

If we set aside slurs for a moment, the main downside is that you don’t have words that do certain kinds of work. The profane words we have in our society are strong — they’re powerful, they provoke emotions. They express emotions. We use them when we’re in pain, frustrated, sexually aroused. They’re as powerful as they are exactly because they’re taboo — because we are violating a norm. To the extent that allowing those words decreases their power, it’s one less tool in our tool belt.

In your book you talk about the way these words interact with the brain. You hurt yourself, stub your toe, accidentally burn yourself on a teapot, and you shout a dirty word. What’s happening there? Does the language do anything to salve the injury?

There are physiological reactions when you swear: increased heart rate, increased blood flow to the extremities, increased sweating of the palms. You enter a fight or flight situation.

There was an interesting study out of Kiel University, in England, that found that swearing actually allows people to endure pain more successfully. They have people stick their hands into near-freezing water, and the group that had been encouraged to swear could hold their hands for nearly twice as long as the group told not to swear.

I’m wondering what drew you personally to this topic.

My primary interest was scientific. My research is on language and the brain and how we use language to communicate. My previous research had been on rational communication of ideas and concepts. But as I looked at how we communicate emotions — how a single member of the species sends a signal through time and space to another member of that species, that allows its current, transient, hot emotional state to come through — profanity is the language we use most readily.

But I wouldn’t have gotten so deep into it if I’d not found profanity fascinating, intrinsically. It’s one of the places you see the most creative language use, and a lot of the entertainment I find the funniest and most compelling uses profanity. For me it’s a way into the human side of how we communicate.