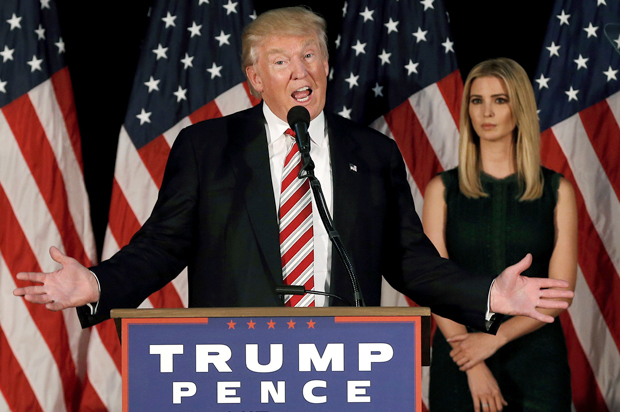

Donald Trump’s presidential campaign is making a concerted push on child-care policy with a brand-new policy outline and a media blitz by his daughter Ivanka Trump. As I wrote yesterday, the rough outline of the policy put out by the campaign looked like a mix of useless and inadequate proposals for tackling the rising costs of child care. Trump’s campaign has added a few more details since then, and his people are now in the midst of a dubious effort to sell the plan as a boon to the working class generally and working mothers in particular.

Ivanka Trump, who is reportedly the mastermind behind this child-care proposal, wrote a Wall Street Journal op-ed laying out the plan and lauding its supposed benefits for working-class parents. Under the headline “The Trump Plan Will Help Working Mothers,” Ivanka wrote that her father “in his campaign for president, has proposed a plan to bring federal policies in line with the needs of today’s working parents.”

Here’s how she described the plan:

Part one is a rewrite of the tax code, allowing working parents to deduct from their income taxes child care expenses for up to four children, as well as for elderly dependents. This will be capped at the average cost of child care in each family’s state, and the wealthiest individuals will not be eligible for the deduction. The benefit is structured to ensure that working- and middle-class families see the largest reductions in their taxable incomes.

So would the child-care deduction provide great tax relief for working- and middle-class families? According to the economists and experts I talked to, no.

“I’m failing to see how the policy would do that,” said Anna Chu, vice president for income security and education at the National Women’s Law Center. “As it stands right now, the structure of the deductions is such that it predominately favors higher-income families,” she noted.

“We know that about 45 percent of people at the bottom of the income distribution don’t really have a tax liability.” Aparna Mathur, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, said. “So to say now you get an additional deduction, it’s really not going to make any impact on your taxes. It’s hardly the way to create the right incentives or provide the right support for low-income households.”

Elaine Maag, senior research associate at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, said, “That policy is designed to help upper-middle-income taxpayers and high-income taxpayers.” She added, “It cannot help low-income taxpayers and that’s because very low-income families do not owe federal income taxes.”

Even for solidly middle-class families, Maag said, the plan isn’t that great a policy. “A middle-income family doesn’t benefit that much from a deduction, and that’s because they pay lower tax rates than high-income families.”

Generally speaking, a tax deduction like this, by its very nature, will be more valuable for those taxed at a higher rate and who can spend more money on child care. “Even if a middle-class family spends the same amount as a wealthy family does for child care, the wealthy family’s tax cut will be larger,” noted Chu.

These criticisms were thrown at Trump when he previewed the policy last month. His campaign was apparently sensitive to the critique, so it decided to throw a bone to low-income families in the form of a “child care spending rebate . . . through the existing Earned Income Tax Credit.” That rebate, which would be linked to employee payroll tax contributions and would max out at $1,200 annually, would provide “meaningful assistance to lower-income Americans who don’t pay income tax,” per Ivanka Trump’s Wall Street Journal op-ed.

As I wrote yesterday, describing a $1,200 credit as “meaningful,” depends largely on where you live — child-care prices are extremely high in places like New York, Massachusetts, California and the District of Columbia, where a year’s worth of care can easily cost $10,000, $15,000 or even $20,000.

Offsetting those costs with a tax rebate may not help too much, especially since child care is a recurring cost throughout the year, while tax refunds typically show up as a lump sum sometime in the spring. “The greater issue for low-income families is if you are cash constrained, it is very difficult for a tax credit, whether it’s refundable or not, to help you with a monthly expense,” Maag said. “The tax code is not a very good tool to help low-income families offset a monthly expense.”

But the tax code is great for subsidizing day care for the children of rich people, who, despite all the “working moms” rhetoric, still seem to be the chief concern of the Donald Trump child-care policy.