Faith and religion are married concepts not often examined separately on television, though adherence to one of those concepts does not necessarily require the other. This means it’s possible to have faith without adhering to any religion, and it’s just as feasible to incorporate religion into one’s life as a ritual or reflex without cultivating a relationship with the divine.

Television portrays religion in a number of ways. What hasn’t been considered as often, though, is the whole purpose of faith — what it is, what it gains us. And what if the omnipotent being whom we call by so many names, refuses to intervene when we need it most? What if it doesn’t know anything?

What if the afterlife, such as it is, is based not on someone’s unquestioning devotion, saying the rosary, making ritual ablutions and reciting suras but instead simply on being good? What if it’s all just based on points?

Two new series, NBC’s “The Good Place” and Fox’s “The Exorcist” look at these questions of faith in very different ways, joining a number of other contemporary takes on the nature of belief and its value.

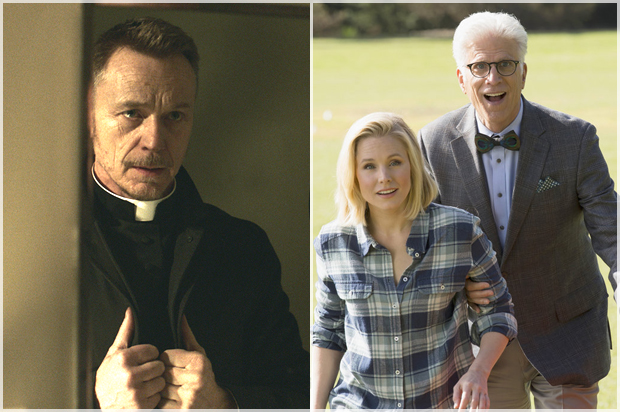

“The Exorcist,” which premieres on Friday at 9 p.m., expands the story of William Friedkin’s 1973 horror classic, and once again Catholic priests are in the hero roles. This being Fox, instead of a young priest and an old priest, we get a hot young priest, Father Tomas Ortega (Alfonso Herrera) and a slightly punk rock middle-aged priest, Father Marcus Keane (Ben Daniels).

While Father Marcus still wears his cleric’s collar, he’s less connected to the trappings of the Roman Catholic Church than to channeling divine power to disperse evil by any means necessary. To him, faith is a sword and shield necessary to battle demons that are all too real. But Rome is a political place that’s done with crusaders like him.

Contrasting the fiery frustration that Daniels gives his character, Herrera’s Father Tomas is kindly and naive and invested in perpetuating religion as a balm. Even so, in an honest moment with a concerned churchgoer who enlists his help, Angela (Geena Davis), he admits having never heard a calling from God.

When he asks her if she believes, she replies honestly. “I like the idea of God,” she says. “I want to believe that good things happen for a reason, and we’re not just a bunch of molecules smashing into each other. But . . . I don’t know.”

Without my having seen beyond the premiere episode made available to critics, I think “The Exorcist” seems to be setting itself up as a study of faith where religion and its related accoutrements are secondary to belief itself. This was the central point of the film upon which it was based, so that’s not exactly a surprising discovery. But in the larger landscape of television right now, and broadcast television in general, it’s also a stealthy tactic to look at the nature, purpose and usefulness of faith separate from dogma.

“The Exorcist” isn’t the first program to do that this year, mind you. It’s been preceded by Cinemax’s thematically similar drama “Outcast,” in which religion does not aid the people of a small town plagued by demons. The man with means of stopping them has given up on God, family and people in general, and knowing that is no comfort to the town’s powerless reverend.

In late spring, Season 1 of AMC’s “Preacher” made debates about the role of faith and the existence of God so central to its purpose that it culminated with the show’s central anti-hero protagonist organizing a videophone conversation between the Almighty and doubting churchgoers.

Given that the titular character is a barely reformed criminal who carries an all-powerful being known as Genesis inside him, it’s no shocker that said chat does not end well. But there, again, is television’s making a commentary on faith in a troubled world where we are accustomed to having verification easily available to us. The citizens of “Preacher’s” Annville were not willing to invest in their holy man without proof. And for better or worse, proof is what they received.

The heroine of Showtime’s “Penny Dreadful,” meanwhile, blindly clung to her faith in God as a barrier between her and the darkness that would result in an end to the world. That she ultimately abandoned her faith had nothing to do with her failure in the end; that could be blamed on that most Victorian of evils, a broken heart.

And remember that one of the most hyped storylines on “Game of Thrones” was set in motion by the loss of faith. Melisandre, the Red Priestess, lost her religion completely when she realized her divinely bestowed visions were false. Her performance of the ritual to raise Jon Snow was mostly done as a favor to those he left behind, and at first it didn’t seem to work. Only at the moment that she accepted her complete failure did Snow gasp into life.

Notice that these shows all hang on supernatural themes. Indeed, genre television and film has long provided creators with the means to approach many existential questions, including dissections of faith, in such an oblique fashion.

Yet The CW’s “Supernatural” took a much more on-the-nose approach, as the show’s hard-drinking, womanizing, nearly faithless Dean asked the show’s version of God the questions we’d want to — mainly why the universe’s all-seeing, all-powerful entity could stand by and watch as heinous things happen to his creations.

“Supernatural,” “Preacher,” “Outcast,” “Game of Thrones,” “Penny Dreadful” and “The Exorcist” all acknowledge that higher beings exist while shattering the idea that piety can gain a person any guarantee of protection or even redemption.

Besides, religion has rules. Once we know the rules, then it’s possible to rig the system. That holds true for humans and demons alike.

Knowing this makes the latest comedy from “Parks and Recreation” creator Mike Schur, “The Good Place,” an interesting proposition: Its paradise is not guaranteed by following any single religion. Rather, access to The Good Place is determined by a morality-based system.

“The Good Place,” which settles into its regular time slot of Thursday at 8:30 p.m. starting tonight, operates on a philosophy that aligns most closely with humanism. As The Good Place’s architect, Michael (Ted Danson), explained in Monday’s premiere, beings of his kind observe the actions of every human, assigning or subtracting points to determine whether they’ll receive entry to The Good Place or go to The Bad Place, which we have yet to glimpse.

As is the problem with all unearthly beings, Michael doesn’t understand all the peculiarities of humans, which means for all his intricate plans, he has yet to notice that his newest charge, Eleanor Shellstrop (Kristen Bell), does not belong in The Good Place. Bell is incredibly enjoyable as Eleanor, who is a terrible person, not exactly Vladmir Putin-awful, but you wouldn’t ever list her as your emergency contact.

But for whatever reason when she died, she woke up to this afterlife that is not Heaven but is similarly based on perfection. In the show, the “best of the best” spend eternity in their fantasy homes with their true soul mates, living among others who were good-to-the-marrow in life and eating as much frozen yogurt as they can handle.

Eleanor lives next to a gorgeous and slightly condescending British woman Tahani (Jameela Jamil), and she can barely stand it, which is problematic: Any time Eleanor’s inner devil gets the best of her, the world around her is impacted. She genuinely must do good, and be good, to escape an eternity of torture. To prevent being shipped downstairs, Eleanor persuades her soul mate Chidi (William Jackson Harper) to teach her how to be a better person.

“The Good Place” is the only half-hour comedy on television right now that extracts its humor from philosophies concerning virtue, belonging and knowledge of the self, and it does so in a way that doesn’t preach or come across as sanctimonious.

Even as it does this in a nondenominational fashion, Schur and his writers pose some important questions about the value of righteousness at the end of the day. Eleanor points out the unfairness of admissions policy for The Good Place because adhering to the Golden Rule isn’t enough to save a basically good person from eternal damnation.

And as the series progresses, it becomes evident that Michael’s idea of what constitutes “the best of the best” among humans doesn’t necessarily translate to people with barely tolerable personalities. But among TV series that make us consider our relationship to belief and faith, this show at least assures us that doing the right thing can be its own reward. Even if being virtuous doesn’t translate into an eternity of creamy frozen desserts, we can feel good about our actions right now, which may be all the certainty we need.